Taking Flight

- Judy Etzel

- November 19, 2021

- Hidden Heritage

- 3793

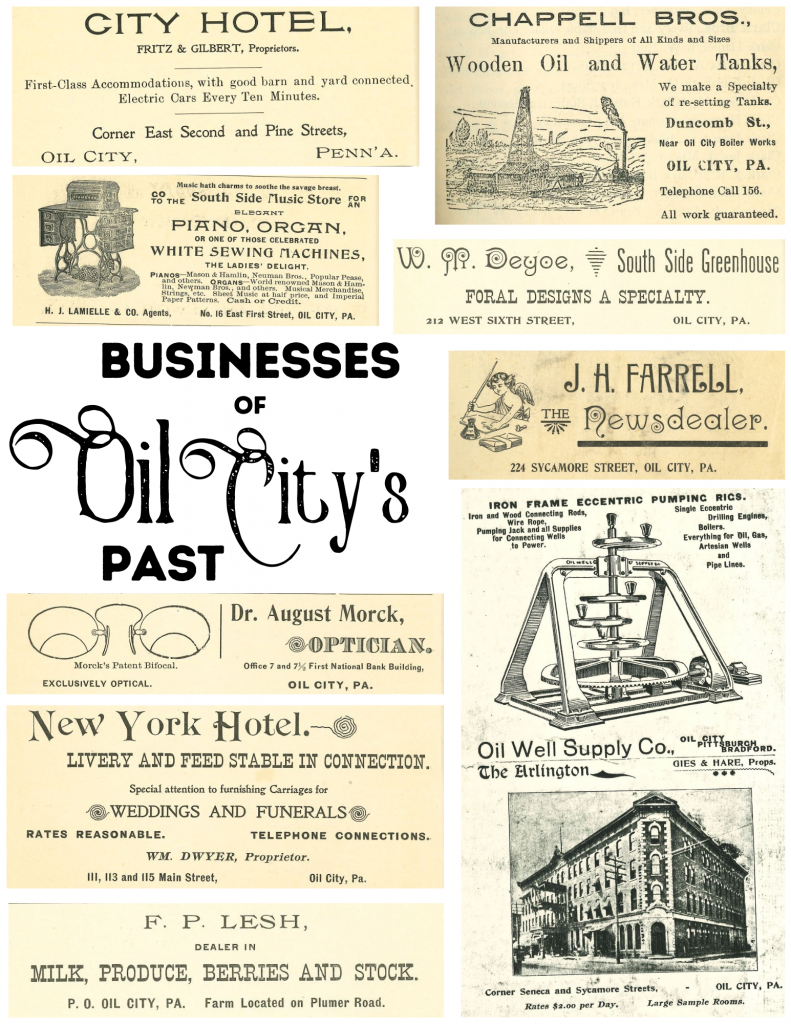

The Oil City area has a strong aviation history, thanks in large part to the fuel it has provided from the prolific oil patch. It also can claim native sons and daughters whose wartime aerial exploits brought praise to their community.

There are other aviation-related ties, too, that drew headlines for daring feats, ingenuity and perseverance.

Lindbergh Was Here

On April 5, 1945, a man piloting a dark blue, single-engine Stenson airplane began circling a hayfield near Fertigs, Pinegrove Township. Snow squalls, plus his worries about insufficient fuel to make the Splane Memorial Airport outside Oil City in Oakland Township, prompted him to make an emergency landing.

It was Charles Lindbergh, the famed Lone Eagle who had made the first trans-Atlantic flight in 1927. According to a published account by Mrs. J.A. DeFrance, a Pennsylvania history teacher at South Side Junior High School, two young students discovered the stranded pilot.

Shurl Stover, 17, had stayed home from school that morning to help with chores on his family farm near the tiny village of Fertigs. His friend, Clair Schwab, had driven home in his Studebaker for lunch and was returning to afternoon classes at school.

Both heard the airplane circling overhead and then saw it land in a 200-acre hayfield owned by the Sharrar family. They rushed to the airplane and saw a youth and an adult male exit the plane.

The pilot told the boys he needed to get to a telephone so he could order a fuel delivery. They drove the pair to the nearby Clifford Stuck residence. They went inside and the pilot was immediately identified by Mrs. Stuck as Col. Lindbergh.

That sent the two boys racing to their school to inform their teacher, Miss Helen Sayers, that Lindbergh had landed. She dismissed classes and the students headed to the hayfield. Word got out quickly about the famous visitors and the site was soon filled with spectators.

Inside the Stuck house, Lindbergh called Splane Airport and ordered fuel. He also reportedly called the United Aircraft Commission in Boston. Lindbergh told the family that he was “on his way from Detroit to Boston on a secret war mission for the government” as a civilian, according to DeFrance’s account.

The younger passenger was identified as Jon Lindbergh, Charles Lindbergh’s second son.

After the plane was refueled, the Lindbergh duo reboarded the aircraft and took off, dipping the plane wings in a tribute to the large crowd on the ground.

The idea of paying attention to aircraft was nothing new to the Fertigs community. DeFrance wrote that an observation tower was erected on a field there during World War II to collect data about airplanes flying through the area. Local men and women voluntarily manned it 24 hours a day.

Across the Pacific

A Titusville man, grandson of oilman and industrialist John J. Carter, was one of a two-man team who made aviation history in 1931.

Hugh Herndon Jr., a Titusville native, joined with Clyde Pangborn of Douglas County, Washington, to make the first non-stop flight across the Pacific Ocean. The Oct. 3-5 crossing covered 4,500 miles from Japan to the U.S. in 41 hours and 15 minutes. The time was almost double Col. Lindbergh’s crossing of the Atlantic Ocean in 1927.

Pangborn, a decorated World War I pilot, founded the Standard Aircraft Corp. where he served as chief test pilot. Herndon joined him as the pilot who demonstrated the company’s planes.

When a Japanese newspaper offered $25,000 in prize money to the first pilots to fly non-stop across the Pacific, they signed up. Pangborn offered the aviation expertise while Herndon supplied $100,000 to buy a plane, customize it and arrange for 930 gallons of fuel.

In Japan, their quest was temporarily delayed when Japanese authorities arrested them and charged them with spying. After several days, the pair was released after they paid a $1,000 fine.

Their aircraft was called Miss Veedol in honor of Veedol Lubricants made from 100 percent Pennsylvania Grade Crude Oil. The Veedol choice reflected the name of the aviation fuel produced by the Tide Water Oil Co. which used PennGrade crude but refined it in New Jersey. Herndon’s mother was heiress to the Tide Water fortune.

The plane was destined to land in either Spokane or Seattle on the West Coast but heavy fog diverted the flight to the small town of Wenatchee, WA.

While the Pangborn-Herndon team set a record, their fame was fleeting due to attention focused on the Great Depression. They were, however, honored at a banquet held at the Titusville YMCA.

“The Queen City was in gala attire, doing the honoring in impressive style,” noted The Derrick newspaper on Oct. 29, 1931. “It is one of the greatest celebrations ever held in Titusville.”

More than 2,000 cheering fans, including many from Oil City, greeted the two fliers as they landed their plane at the Titusville airport.

Later, both men continued their aviation careers in World War II. Pangborn delivered military aircraft to England. Herndon served as a captain in the Royal Canadian Air Corps and later worked for TWA airlines.

Herndon is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in Titusville. The Miss Veedol airplane was eventually sold. The plane and its pilot were reportedly later lost at sea.

Only Wolf’s Head

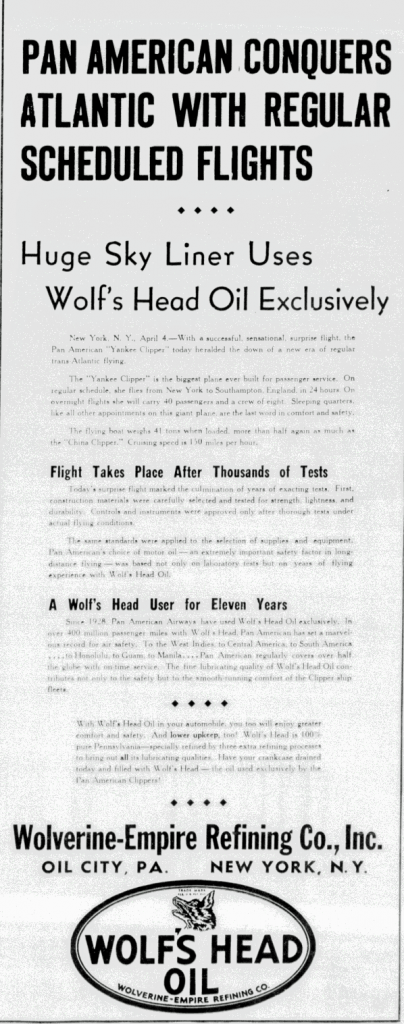

Pan American Airlines launched its trans-Atlantic Clipper passenger service in March 1939. It was considered the largest plane ever built for passenger service and could hold 40 passengers and 8 crew members.

The Clipper could fly from New York to Southampton, England, in 24 hours and was considered “the last word in comfort and safety.” Its cruising speed was set at 150 miles per hour.

When the U.S.-to-England flights debuted, newspaper ads touted the PanAm Clipper service as well as its lubricant of choice: Wolf’s Head.

“PanAm’s choice of motor oil is Wolf’s Head: 100 percent pure Pennsylvania oil is used exclusively by Pan American Clippers.” The printed advertisements were paid for by the Wolverine-Empire Refining Co., maker of Wolf’s Head.

Oil City Air Mail

The wealth in the Oil Valley produced some interesting footnotes, not least of which is the advent of air mail service.

The Oil City Glider Club was organized in 1931. Members used the Splane Memorial Airport in Oakland Township. It boasted a paved runway and several plane hangars and was the site of air shows and a flying school.

Club members were keen on expanding services and projects and on May 18, 1938, the club, then renamed the Oil City Aero Club, arranged the first air mail flight from Oil City to Pittsburgh.

The pilots were H. Douglas Brown and Richard Lobaugh, who co-piloted one plane, and D.V. Summerville, Clyde Thompson and Walter Foust. In all, four planes provided the service.

Howard Hughes Saved

An Oil City man drew national headlines when he saved the life of millionaire movie producer and pilot Howard Hughes on July 7, 1946, in Beverly Hills just outside Los Angeles.

He was William “Red” Durkin, son of Thomas and Ethel Durkin. The couple and their five children lived on Washington Avenue in Oil City.

Durkin joined the Marine Corps at age 20 in 1936.

His involvement with Hughes came a decade later.

Hughes was flying an $8 million prop-driven prototype plan, the Hughes XF-11, on its maiden voyage. Less than an hour into the flight, the plane went into a nosedive and struck three homes in Beverly Hills.

William Durkin, a Marine sergeant from Oil City who was stationed at the El Toro Marine Air Station, was napping after working at the air base all day. He heard the roar of plane engines less than a block away and knew the plane would crash. He ran outside, saw the aircraft hit the ground and explode into flames.

Durkin rushed to the fuselage, grabbed Hughes, whose clothing was on fire, by the shirt, pulled him out of the wreckage and dragged him away from the plane. Medical personnel quickly responded and transported Hughes, who was badly injured, to a hospital. Durkin suffered only what he described to the news media as “singed hair.”

There were rumors that Hughes, who recovered but remained addicted to the painkillers he was given after the accident, offered $100,000 to Durkin for saving his life. Durkin refused, saying that he was only doing what anyone else would have done in the same circumstances.

Durkin was honored, though, by the Marine Corps for “non-war heroism.” He was presented the Navy and Marine Corps Medal and had an extra $2 added to his monthly service pay.

Shortly after the accident, Hughes sailed with his Marine unit to China. He served in the World War II battles at Guadalcanal and Okinawa and later earned a battlefield commission for a captain’s rank in Korea.

Durkin served 30 years in the Marine Corps, retiring in the mid-1960s. He and his family moved to Palm Springs, CA. He gave his engraved officer’s sword to his nephew, Chris Nelson of Oil City, who was in the Marine Corps. Chris, a 1979 graduate of Venango Christian High School, did graduate work at the University of Chicago and was employed as a faculty member at the University of North Carolina.

Chris described his Uncle Bill in a later newspaper interview as being “a real Marine’s Marine.”

Piper Cub

The popular Piper Cub airplane, a two-seater lightweight aircraft, was designed and manufactured in Bradford.

William T. Piper, a multi-millionaire from Bradford, was an industrialist and inventor. In 1930 he formed Taylor Aircraft to produce an airplane that was designed “to encourage greater interest in aviation.”

The popular Piper J-3 Cub was produced until 1937 in Bradford until a fire destroyed the plant. The operations were then moved to a former factory in Lock Haven.

The aircraft could hold two people and boasted a maximum speed of 88 miles per hour.

It was affordable, simple and lightweight, attributes which lent a comparison to Ford’s Model T version of a car meant for the general population.

HIDDEN HERITAGE IS SPONSORED BY:

YWCA of Oil City

Michael Schneider

Mary Ann & Jim Brown

Support This Project

Donations to the library are appreciated to help offset printing costs & make this project possible! Want to become a sponsor? Email us at promotions@oilregionlibraries.org to get started!

Make a Donation