Wharfs & Steamboats

- Judy Etzel

- June 9, 2023

- Hidden Heritage

- 14121

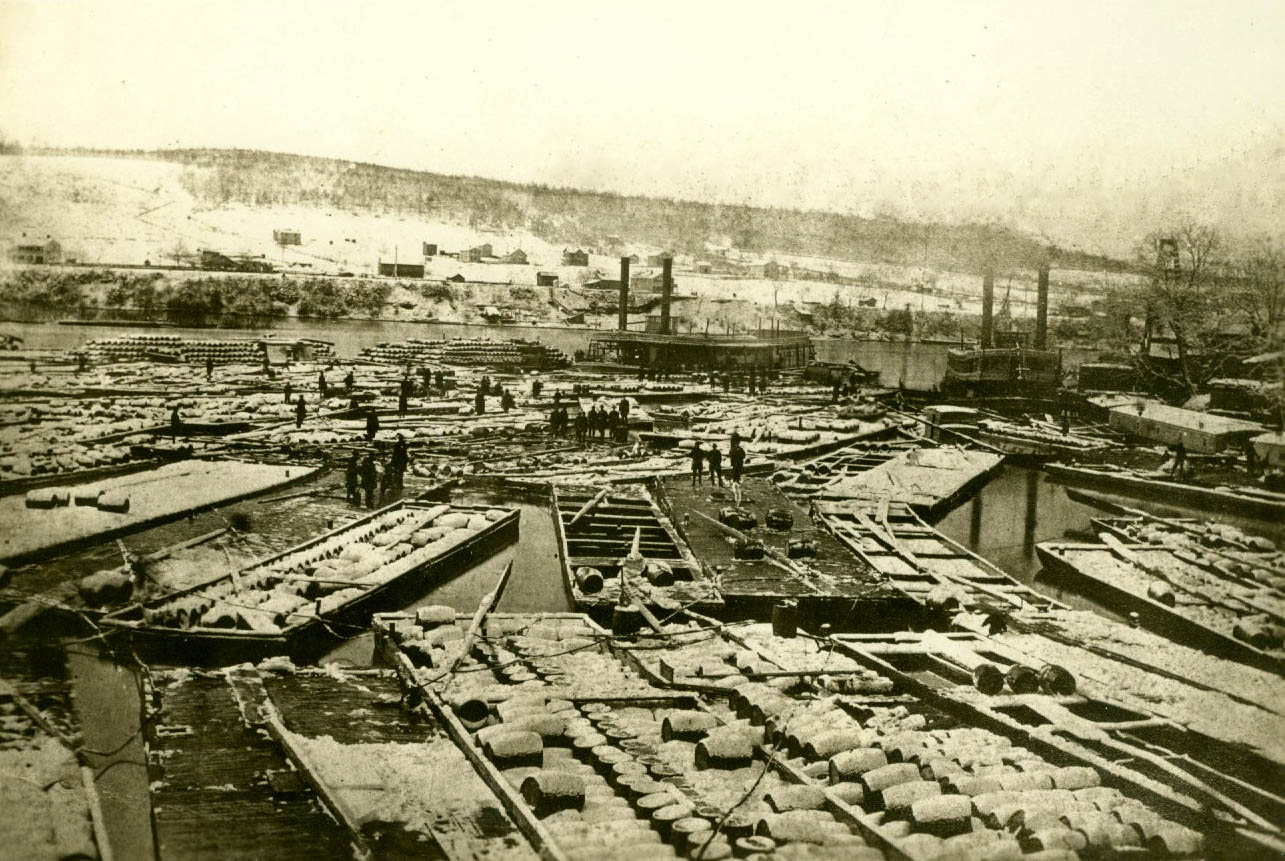

The Allegheny River was a prime transportation route for all manner of goods for more than 200 years.

The original river traffic focused on cut timber that was loaded in communities up and down the river and sent south to the larger cities, especially Pittsburgh, to meet consumers’ needs.

Then came the iron ore industry that shuttled iron from the region’s many iron furnaces to smelting operations downriver.

Barges laden with those goods were often tied up to large iron rings drilled into large rocks along the river banks. Rafters would tie up at those spots for the night and then resume their passage the next day. The oil industry fueled the largest boom in river traffic as flatboats and barges hauled oil-filled barrels from oil fields to refineries.

The river also boasted an array of steamboats that plied the waters to bring visitors and business representatives to the bustling Oil Valley. Two-way commercial traffic between the headwaters of the Allegheny River south to Pittsburgh was hefty. The fare for the Pittsburgh-to-Oil City run was set at $5 in 1887. The 135-mile trip took between 30 and 36 hours.

Oil City was a key location for river traffic. Wharfs lined both sides of the Allegheny River in Oil City and the owners enjoyed a lucrative trade.

A colorful telling of Oil City’s steamboat and barge business was written by Walter J. Johns in 1866. It was recounted in a June 28, 1890, newspaper column entitled “Oil City Chroniclings”. It offered, noted the author, a “brief description of the bustling oil industry.”

“Until the start-up of railroads and pipelines, the systematization of the Allegheny River oil transportation had already attained such vast proportions.

Prominent among these, who were both dealers and shippers and warehouse men as well, were Capt. J.J. Vandergrift, Hanna Bros, the Mawhinneys (John and James), the Fishers (John J., Henry and Fred); Dilworth and Ewing, T. B. Porteous, Pat Tiernan and others.

The best route to the Oil Country, via Oil City, was by steamboat from Pittsburg in seasons when the stage of water was admitted. This varied, but the general average was several months of the year. The Bridge over the Allegheny at Emlenton was an obstacle when, owing to high water, steamboats could not pass under it. And occasionally on account of low water the boats were forced to return to Pittsburg when their voyage was only partially completed.

In such cases the unfortunate passengers, unless they were fortunate enough to secure the services of a farmer and his team along the route, ‘footed’ it over the almost continuous hills of Clarion and Venango counties to Oil City. Such inconveniences were regarded merely as incidental to the trip. True, there were other routes by which the traveler came to the nearest station of the main railroad lines traversing this portion of the state. But from thence to their destination- the Oil Country – an overland journey of from 30 to 40 miles was requisite. So the advantage, as far as comfort went, was in favor of the Pittsburg route.

The principal passenger steamers of 1862 were the Allegheny Belle, Capt. William Hanna; the Leclaire, Capt. Kelley; and the Echo, Capt. Zeke Gordon.

To those who were so fortunate as to have taken a trip with either of these worthy gentlemen, no comment is necessary. Staunch boats, perfect service, thoroughly experienced gentlemen for commanders, and the finest natural scenery in the country to pass through, was among the inducements offered. But when one wearied of these, the comfortable appointments of the cabin were available. Then the table fare, and the clean, comfortable state-room made a sum total of enjoyment sufficient for the requirements of average mortals. We confess to a human weakness for something good to eat, and a clean, comfortable bed to rest our frame when courting Nature’s balmy restorer.

By no other mode of travel have we found the same excellence of cuisine and of a restful couch as were provided on those passenger steamboats. And this, too, at a price moderate enough to suit the ordinary purse.

The shrill and not unmusical whistle sounding just below Moran’s Island, announcing the arrival of a steam boat ‘from below’ was ever most welcome to our residents.

Of course such mode of travel is not suited to the present time. Now the trip is made in an ill-ventilated railroad car where one only catches a glimpse of the country passed through while flying along at the rate of 30 to 40 miles an hour. The fare to be had at the average railroad restaurants is not always inviting and seldom tends to healthful digestion. As to the comforts of the modern palace car – well, we, for one, fail to realize it in comparison with our favorite mode of steamboat travel.

The steam boat and the oil boat passed away soon after the completion of the Allegheny Valley Railroad to this point in 1868. The pipeline relegated the teamster and his team back to the farm or to the ordinary uses of trade and traffic. It required but a brief time to rid the shores of the river and creek of the hundreds of oil boats and their picturesque surroundings. The final disposition of these has ever been as puzzling a problem to us as that of ‘where the pins go to.’

An occasional length or so of piling is all that is left of the old steamboat landings, and the extensive shops of the National Transit cover a large portion of the olden oil yards.”

– By Walter J. Johns

Early Oil City records show the city boasted numerous wharfs to handle a variety of river traffic. All were located along the Allegheny River with the primary wharf locations situated just off Main Street. The 1866 city directory had a listing of steamboat and barge landings in the city. They included:

- Bushnell’s Landing, foot of Chestnut St.

- Benny, Baylis & Co., 244 Main St.

- Cochran’s, 298 Main St.

- Dilworth & Ewings, foot of Robson St.

- Ellison & Baxter’s, foot of Walnut St.

- Fisher’s, foot of Hanna St.

- Fisher’s, No. 2, foot of Chestnut St.

- Fawcett Bros., foot of Chestnut St.

- Gallagher & Danver’s, foot of Walnut St.

- Haldiman & Murray’s, 242 Main St.

- Jackson’s, 290 Main St.

- Lucesco Oil Co., foot of Oak St.

- Munhall’s, foot of Chestnut St.

- McKelvey & Miller’s, foot of Walnut St.

- Mawhinney’s, 262 Main St.

- Oil City Storage Co., foot of Oak St.

- Parker & Castle’s, foot of Parker St.

- Porteous, foot of Walnut St.

- Phillips & Co., foot of Hanna St.

- Vandergrift’s, foot of Chestnut St.

Sarah Gayle

The obituary of an Oil City woman in 1952 offers a glimpse into commercial river traffic in earlier times.

Sarah E. Gayle of 412 Second Street died at the age of 105. She was the oldest person in Venango County and believed to be the oldest person in Pennsylvania.

She was born in September 1847 in Blairsville, Indiana County. Her father, Adam Turner, was a merchant. The family moved to Worthington, Armstrong County, where he worked as manager of the Buffalo Iron Furnace.

In November 1861, the Turner family decided to move to Oil City to take advantage of the oil-fueled boom.

They left Kittanning aboard the 127-foot-long steamer LeClaire, and traveled up the Allegheny River to Oil City. Their household goods came by a later boat, but were carried away when the river rose overnight while the boat was docked at Hanna’s Wharf off Main Street.

In remembering the trip, she noted the excellent food and service aboard the boat and said she had “never in her life seen as many cream pitchers as she did at the tables aboard the LeClaire.”

The family lived on a farm slightly above what would become Siverlyville. Sarah’s father went into oil production.

They later had a house built on Colbert Avenue and the residence became known as the first house with plastered rooms in Oil City.

The family lived on a farm slightly above what would become Siverlyville. Sarah’s father went into oil production.

They later had a house built on Colbert Avenue and the residence became known as the first house with plastered rooms in Oil City.

During the administration of President Lincoln, Turner was appointed to be an internal revenue assessor for the Oil City area. He had a busy job as taxes were levied on the petroleum industry.

In a newspaper account about her birthday, she recalled that when her father was a revenue collector, Coal Oil Johnny and a companion galloped up to the door of the Turner home one night around midnight.

The entire family was awakened as the young millionaire, Johnny “Coal Oil” Steele, demanded a correction on his income return.

Gayle said she remembered that Race Street (now Seneca Street) was so called because of mill races along Oil Creek.

Dams to the races had to be opened for freshets bringing oil barges down the creek.

She remembered how in August 1862, Capt. Hasson and departing Civil War soldiers were given a dinner in a beautiful grove of trees on West First Street near the old mansion, once known as the Venango Club.

She also recalled how in 1883 she carried food and linen for bandages to those injured in the old Cranberry train wreck near East Second Street.

Gayle noted in the interview that cars, coal and human beings were strewn everywhere. A heavily loaded coal train had become unmanageable upon the steep grade and ran wild. Several persons were killed and a number injured. The City Hotel was turned into a hospital.

She married Archie Gayle who worked as a baggage agent for the Pennsylvania Railroad. They had one daughter, Bess, who later taught at Innis Street School.

Archie died in 1919.

At age 100, she walked from her home to a Fourth Ward polling place to cast her ballot in 1947.

The article also noted that Sarah attributed her original, full set of teeth to using “plain table salt” as her tooth powder.

She was a charter member of Second Presbyterian Church.

DID YOU KNOW?

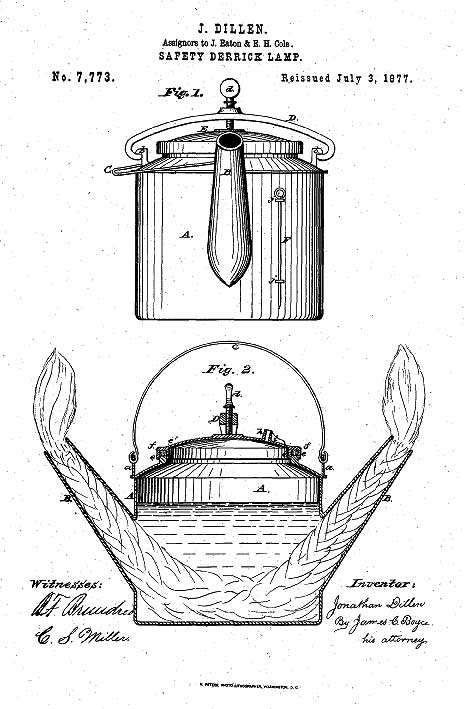

The famous Yellow Dog Lantern, a two-wicked lamp used in the early oil fields, was first patented by inventor Jonathan Dillen of Petroleum Center in 1870.

The design, according to the inventor, was to provide illumination “in and about the (oil) derricks.” The patent was eventually assigned to John Eaton and E.H. Cole in 1877 and they redesigned it to use crude oil directly out of a well.

A year later, the two men founded Oil Well Supply Co. in Oil City and included the manufacture of the Yellow Dog Lanterns in their catalog. In 1884, the catalog price for an Oil Well-made iron Yellow Dog Lantern was $1.50 each.

Two reasons for the yellow dog name: legend says the burning wicks looked like a dog’s glowing eyes in the dark, while other folklore suggests the lantern’s shadow on the floor resembled a dog’s head.

Written by Judy Etzel with research by Kay Dawson and design by Natalie Cubbon.

HIDDEN HERITAGE IS SPONSORED BY:

Jack Eckert & Susan Hahn

— In Memory of Carole Eckert —

Support This Project

Donations to the library are appreciated to help offset printing costs & make this project possible! Want to become a sponsor? Email us at promotions@oilregionlibraries.org to get started!

Make a Donation