Clark’s Summit

- Judy Etzel

- January 21, 2022

- Hidden Heritage

- 5327

The first permanent settlers in what would become Oil City were Frances and Sarah Halyday who bought 400 acres that spanned an area from the confluence of Oil Creek and the Allegheny River up over the nearby hill. The year was 1803.

It is the oldest section of the city and would eventually acquire the name Clark’s Summit and Lover’s Leap. Much of the property would become the centerpiece of what two entrepreneurs hoped would evolve into an elaborate neighborhood layout atop the hill. It was destined to fall short.

Transfer of Property

In 1860, the Michigan Rock Oil Co. bought a large swath of the Halyday property with the intent to drill wells along an area at the foot of the hill. Land on the hillside and hilltop remained untouched.

That changed in 1871, the same year that the City of Oil City was incorporated. Local residents Philo M. Clark and Thomas Porteous, both lured to the region by the oil boom, bought land from the Michigan Rock Oil Co. with an eye to develop a residential area on the hill.

The newly incorporated city had room to grow, believed the business partners, and they could offer a prime location for new housing. In the year of incorporation, the city boasted a population of 7,000 and the need for housing was keen.

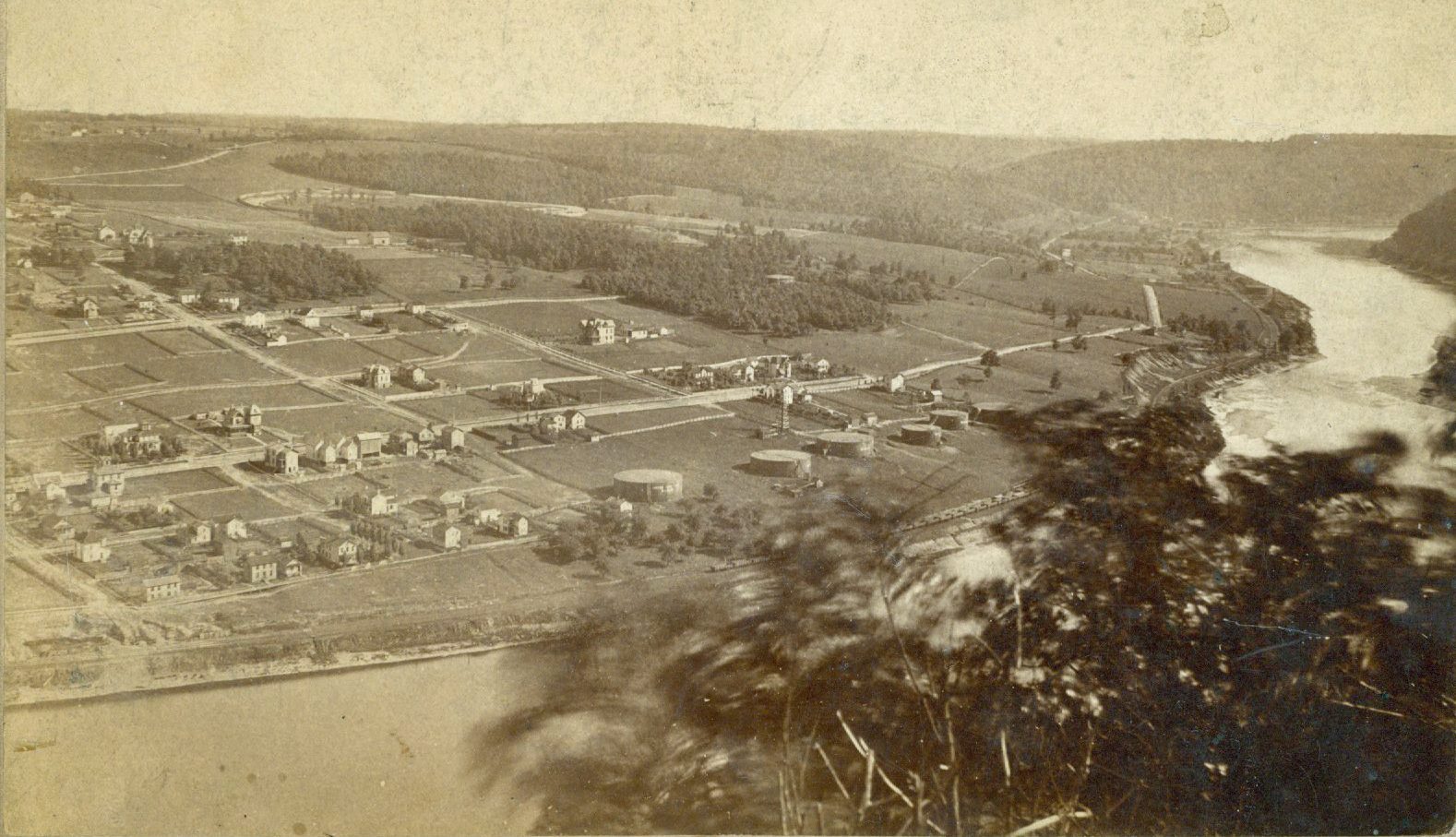

In 1872, the two businessmen laid out neat, rectangular lots on the summit, named Clark’s Summit in honor of Philo Clark. The project was described by the newspaper as “one of the most ambitious and grandiose housing project plans in the Oil Region.”

Since the development coincided with the city’s new stature as an incorporated city that included the South Side and North Side communities, Porteous and Clark decided to name the future streets after the first mayor, William Williams, and leading city officials, including councilmen. They were John Mawhinney, John Evans, William Duncan, Charles Shepherd, William Dwyer, George Parker, T. H Williams, Samuel Irvine, Joseph Bates, R.D. McCreary and Joseph McElroy. Porteous, too, had a street named after him since he was a member of the first council.

The property was divided into 50-foot lots and each was offered for sale at $365. However, only a few named streets would ever have homes built on them. Most of the building was on Dwyer Street and newly labeled streets Tiernan and Cornwall.

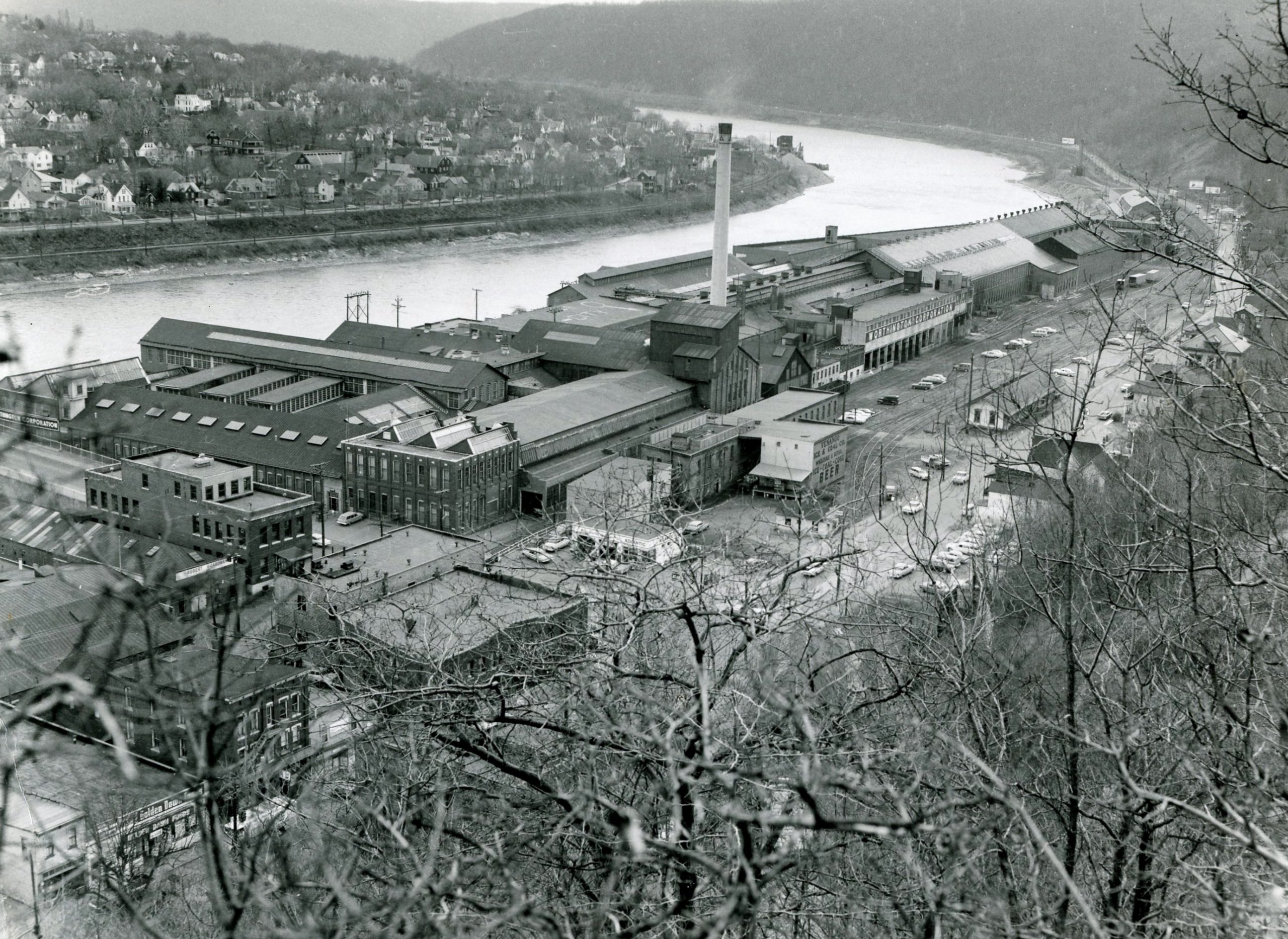

As the City of Oil City quickly grew, most of the housing attention was aimed at the South Side and that drew interest away from the Clark’s Summit development.

That was accelerated when the Allegheny Valley Railroad set up a major operation in the city’s East End and that prompted businesses to flow to the South Side. It became the favored residential building site. In addition, the Cottage Hill neighborhood on the North Side was quickly expanding.

While the efforts to lure homebuilders were falling short, Clark’s Summit still drew large crowds for three amenities: a horse racing track, a ballfield and an incline railroad.

The hilltop’s one-mile long race track was a key attraction within the city. In a 1904 column in the Weekly Derrick newspaper, the writer recalled the racetrack and noted, “In its day it was the scene of speed and betting contests which had a national interest.” The expansive ballfield drew both local and out-of-town baseball teams and frequent games drew large crowds.

However, neither the race track or the ballfield remained in operation longer than a few years. Competing on the race circuit were tracks at what would become Bouquin Circle and the Hasson Heights ballfields. Meanwhile, baseball fields were numerous throughout the city and more accessible to fans.

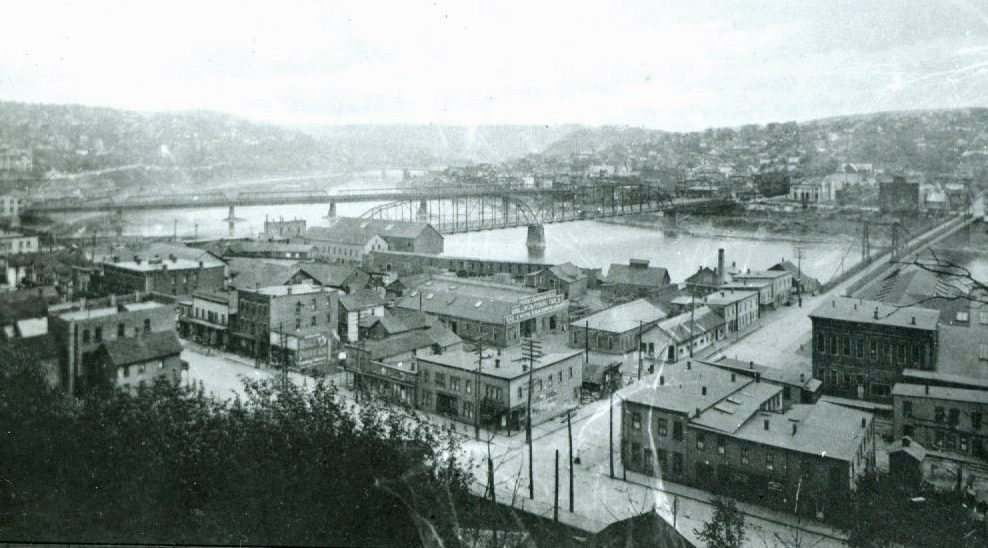

Still, the panoramic view of the city sprawled along the Allegheny River was spectacular from Clark’s Summit and it drew a steady stream of people. “The view from the summit is a veritable map of historical landscape right under one’s eyes, a vast stage on which were played the storied events of a time and a valley that changed the nation,” wrote former Oil City Mayor Joseph Barr to a hilltop property owner in 1987. It was the incline, though, that was the attention-getter for the Clark’s Summit development.

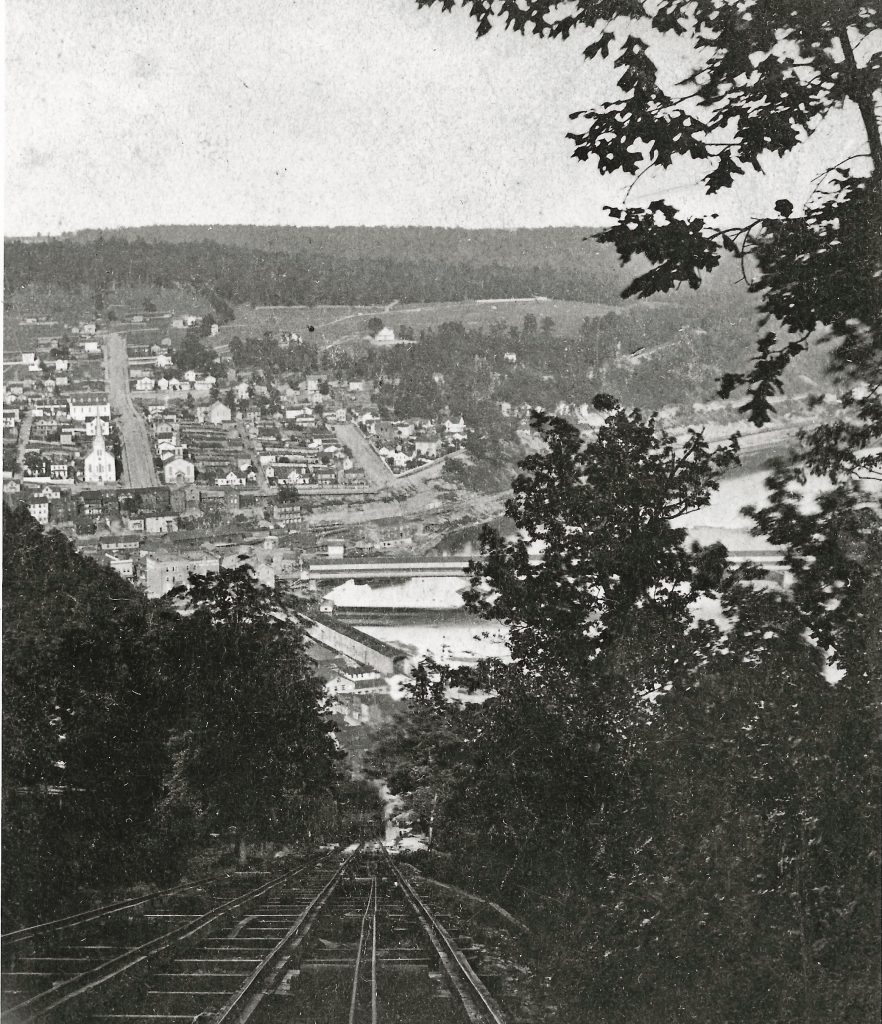

In 1872, Clark and Porteous had a 1,660-foot-long, two-car incline built from Main Street at the foot of the hill to the very top of Clark’s Summit. It rose 450-feet above the city and cost $35,000 to build. The double track was laid at a pitch of 16 degrees, a pitch described in a news account that was “not so steep as many city streets and no more difficult.” The grade was uniform because deep cuts were made into the rocks on the hillside.

There was an upper landing and a lower landing, each manned by an operator. Stationary steam engines were installed at each landing. Heavy wire cables were attached to each of the cars with one car being raised while the other was being lowered. The system had so many safety features compared to the winding road up the hill that a news reporter wrote, “No one … who rides over the road once will ever feel the least ‘skeery’ on that line.”

“As the inclined railway to Clark’s Summit approaches completion, the magnitude of the enterprise begins to force itself on public attention,” wrote the newspaper. “The event is of such epochal importance in the history of our onward march that it deserves special mention herein.”

The cable cars ran every three minutes during the day. The cost was 10-cents per round trip. The car capacity was 10 passengers. The conductor did not travel with the car but remained at the lower depot to collect fares. He ran the trains by signals via telegraph and a bell in the engine house at the top.

A newspaper advertisement plugged Clark’s Summit as an educational tool: “Strangers visiting the Oil Region can in no way obtain a knowledge of the geological formation and general features of the oil country than by taking a trip on the incline.”

Within just a year or two of its opening, the incline’s ridership was soaring. Clark’s Summit was visited by an average of 6,000 people each month during the summer as patrons attended ball games, horse races or simply wanted a ride on the incline.

However, hard economic times and the shift of interest to other areas within the city soon resulted in a lack of incline rail patronage and declining attendance at the ballfield and racetrack because of competition elsewhere within the city.

In addition, there were continuing issues related to defective rights-of-way and land titles on the hilltop. The city was also feeling the effects of the 1873 national economic malaise with the dramatic drop in oil prices.

The incline was dismantled in 1880 and that soon led to the demise of the race track and ballfield activities.

Lack of access to the hilltop created a controversy in the late 1920s when mill workers whose jobs were in plants along Main Street went to city council and demanded that city steps leading up the hill to the summit be built.

When council balked, the residents said they would stay at city hall until council took action. In addition, they threatened to “start throwing councilmen out the windows.” Under duress, Mayor Thomas Blair agreed to the request and the steps were constructed.

The city steps again were in the news in 1976 when the city ordered the 365 city steps leading to the summit be closed because they were in such poor shape. Residents insisted they be replaced because they were frequently used by school students. The passageway continued to disintegrate and the steps were finally removed.

In 1971, there was an effort to revitalize the Clark’s Summit area. City officials applied for funding through the Pennsylvania Project 70 program under former Gov. William Scranton. The idea was to use a grant to buy 261 acres on Clark’s Summit and along the Allegheny River frontage to build hilltop camping grounds, picnic sites, a skiing facility and an observation point. The riverfront acreage was earmarked for hiking trails, boating, docking and fishing.

The grant funding was not approved and the plans were scrapped.

Incline Accident

One of the most spectacular rail-related incidents in Oil City happened on a short and distinctive track leading straight up and down a hill.

The double-track incline railroad was put up for sale shortly after it closed due to economic misfortunes. In the winter of 1880, a Schuylkill County coal company bought the iron tracks with the intention to move them to one of their mines at Tamaqua.

They decided on an unusual way to dismantle the tracks as a result of the cold, icy weather. Workmen removed the spikes from one track so they could drag off an entire track at one time rather than remove it in sections.

The track came loose and rushed down the hillside. The rails became disconnected and went airborne. It was, described one news account, as if “the world’s largest javelin spear” had been thrown. Pieces of heavy track went everywhere and many landed on buildings along Main Street at the bottom of Clark Summit. One large piece slammed through the kitchen wall in the James Hotel. Several young women were working in the kitchen at the time and, reported the local newspaper, “if the line of iron had kept straight on there would have no doubt been four or five funerals.”

Some pieces flew as far as 300 feet through the air. One beam went right through the Kay family’s barn. Also damaged by the rail sections was the Atlantic House, the McKim and Lindesmith homes. An outhouse was leveled on another property while a piece of iron plowed up a garden. Shingles were torn off rooftops and chimneys were knocked down.

No one was badly injured or died in the mishap but a horse, according to reports, had to be shot because of its injuries when hit with a piece of iron. The coal company changed its plans and took the second set of rails off in sections.

DID YOU KNOW?

The Oil City Police Department once had its own police dog, but it was an unusual breed for such a tough job. It was a little Scotch Terrier named Fannie and she was used by police officers to scare away stray dogs. “It may be seen at any hour of the day or night with some member of the force, often entering downtown businesses as the force makes its rounds,” noted the local newspaper in 1888.

Clark & Porteous

The two men who launched the Clark’s Summit project were successful businessmen prior to becoming property developers.

Thomas Porteous, born in Scotland, came to the U.S. in 1855 with his wife, Annie. He was listed as an oil dealer in the early Venango City directory and also owned landing and storage sheds at the foot of Walnut Street.

Active in the community, Porteous was a member of the first city council serving the newly incorporated Oil City in 1871. At that time, he was described in the press as “one of the most successful and prominent men in the oil region.”

Porteous was one of the backers of the President and Pithole Railroad. He lost a lot of money, though, when the venture collapsed.

When the Clark’s Summit land development effort collapsed, Porteous again lost money but he shouldered the burden. He assumed most of the debt for the incline railroad in order “to prevent loss to others,” he said. While urged to file for bankruptcy as well as launch a lawsuit against his fellow investors, Porteous refused and said, “He would leave (earth) with a clean sheet.”

Later stories noted Porteous paid off all his debts and still managed to leave a small fortune to his family.

Philo Clark, born in Massachusetts, had a soda water bottling business in Memphis, TN, and later Louisville, KY, where he supplied soda water to Union troops during the Civil War.

He came to Oil City with his wife, Annie, in 1865 and established a soda water bottling operation in the city. While operating that, as well as serving as a real estate agent, Clark joined with Porteous to develop Clark’s Summit. He died in Kansas in about 1918.

Written by Judy Etzel with research by Kay Dawson and design by Natalie Cubbon.

HIDDEN HERITAGE IS SPONSORED BY:

Oil Region Alliance

Belles Lettres Club of Oil City

Gates & Burns Realty

Support This Project

Donations to the library are appreciated to help offset printing costs & make this project possible! Want to become a sponsor? Email us at promotions@oilregionlibraries.org to get started!

Make a Donation