Contagion

- Judy Etzel

- July 30, 2021

- Hidden Heritage

- 2592

The threat of health scourges from polio to influenza, cholera to coronavirus, is a topic that finds its way into municipal codes that oversee everything from parking violations to natural disasters.

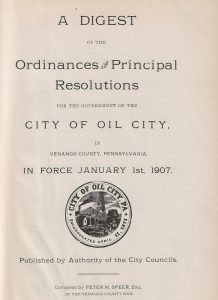

The Oil City 1907 Digest of Ordinances and Resolutions includes a detailed section on “communicable diseases”. The entry sets out the rules and regulations for all phases of a health emergency and they range from anti-contagion measures to burial procedures.

Here’s a Look at the City’s 1907 Rules:

- The following diseases are declared to be communicable and dangerous to public health: smallpox, cholera, scarlet fever, measles, diphtheria, typhoid fever, yellow fever, cerebral-spinal meningitis, epidemic dysentery, rabies, leprosy, whooping cough and mumps.

RULES

- No child can attend public schools who has not been vaccinated. If poverty does not allow vaccination fees by the doctor to be paid, present the bill to the city and it will be paid.

- A patient with a communicable disease who is confined to the premises must not be removed from the premises for fear of exposure. That applies also to items owned by that person.

- No person recovering from a communicable disease is permitted to ride in any conveyance without first notifying the owner of the facts. If a person does ride, the owner must disinfect it first before anyone else can ride.

- The same applies to rooms or buildings that are leased. They must be disinfected before they can be leased again.

- Animals with a communicable disease cannot be buried within 500 feet of any residence.

The City of Oil City had a comprehensive list of regulations pertaining to contagious diseases. The city’s 1907 ordinance book outlined what detailed health procedures must be followed.

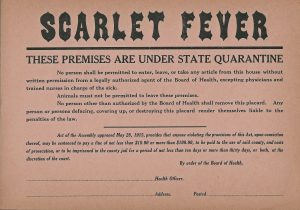

QUARANTINE

- No child living in a home with a communicable disease can leave to go to school, church or any gathering (public or private), to ride in any vehicle used by the public, to mingle or play with other children. The time limits are: three weeks from onset of chickenpox (or when every scab falls off); six weeks for small pox and scarlet fever.

- The same rules apply to adults.

- The loaning by libraries of any book, paper or periodical to any person sick with a communicable disease or to persons in whose families that has occurred is strictly prohibited for fear of spreading contagion.

- All clothing, bedding and any rooms, including furniture, of a person sick with a communicable disease must be thoroughly disinfected under the supervision of a health officer.

- There shall be no public or church funeral service of any person that has died of a communicable disease. The family of a deceased member must limit attendance to as few persons as possible at any memorial service. The death of any person from a communicable disease shall have the name of that disease that caused the death appear in the public notice.

- In the case of a victim of a communicable disease, the body must be completely enveloped in a sheet thoroughly saturated with a strong solution of bi-chloride of mercury in the appropriate proportion. The body must then be placed in a cotton-lined coffin. Cemetery associations are prohibited to receive bodies unless prepared that way. No body of a person dead from a communicable disease shall ever be exhumed or removed.

One specific ailment drew special attention from health authorities in Oil City during the early 20th century.

Oil City had specific health regulations regarding tuberculosis. Physicians were ordered to report to the city board of health, in writing, the name, age and address of any patient they were treating for TB. The same reporting requirements were levied on any proprietor of a boarding house or hotel in which a tenant was suffering from the disease. Extensive disinfecting measures were to be taken and those included a full fumigation of the dwelling, furniture and other belongings. Penalties included hefty fines and possible jail time.

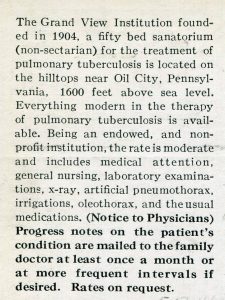

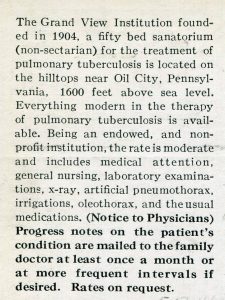

The Oil City area was served by a facility designed specifically to house and treat individuals diagnosed with TB. It was the Grand View Sanitarium, started in 1904 on the former Folwell Farm in the city’s Hasson Heights neighborhood. The initial project was founded and endowed by oilman S.Y. Ramage and was described across the U.S. as “one of the first sanitariums in the U.S. for the treatment of tuberculosis.” Incorporated in 1905, the facility was “to be used for the purpose of maintaining thereon a hospital for the care and treatment of those suffering from tuberculosis.”

The Grand View Sanitarium opened in the former Folwell Farm in 1904 in what would become Oil City’s Hasson Heights neighborhood.

In 1924, a campaign led by L.H. Gavin of Oil City raised nearly $34,000 to pay off the sanitarium’s indebtedness, improve the property and “carry on the work.”

A newspaper article noted: “This institution is now doing splendid work among those suffering from tuberculosis but more can be helped. Money would make it possible for the institution to accept advanced cases. These constitute a great menace to other people as the danger of contagion is greatest from them.”

A newspaper article noted: “This institution is now doing splendid work among those suffering from tuberculosis but more can be helped. Money would make it possible for the institution to accept advanced cases. These constitute a great menace to other people as the danger of contagion is greatest from them.”

In exhorting the public to chip into the campaign, the news story noted, “You owe it to the patients at this institution and to those who will be admitted in the future. Some of these patients are former servicemen. They contracted tuberculosis as a result of the things they were exposed to during the war. They served us then, now we have the opportunity to serve them and surely we will respond in the manner which these young men deserve.”

In 1943, an acute shortage of nurses due to World War II caused the sanitarium to close its doors. That same year, a proposition was put forth to convert the property, which included dormitories, a lab and an administration building, to the Edith C. Justus Orphans Home. However, that eventually went by the wayside as the county court broke up the Justus Trust “because there is no longer a need for this type of orphans’ home.” The property was eventually purchased by Dr. T.S. Gabreski and changed to a nursing home.

Written by Judy Etzel with research by Kay Dawson and design by Natalie Cubbon.

The threat of health scourges from polio to influenza, cholera to coronavirus, is a topic that finds its way into municipal codes that oversee everything from parking violations to natural disasters.

The Oil City 1907 Digest of Ordinances and Resolutions includes a detailed section on “communicable diseases”. The entry sets out the rules and regulations for all phases of a health emergency and they range from anti-contagion measures to burial procedures.

Here’s a Look at the City’s 1907 Rules:

- The following diseases are declared to be communicable and dangerous to public health: smallpox, cholera, scarlet fever, measles, diphtheria, typhoid fever, yellow fever, cerebral-spinal meningitis, epidemic dysentery, rabies, leprosy, whooping cough and mumps.

RULES

- No child can attend public schools who has not been vaccinated. If poverty does not allow vaccination fees by the doctor to be paid, present the bill to the city and it will be paid.

- A patient with a communicable disease who is confined to the premises must not be removed from the premises for fear of exposure. That applies also to items owned by that person.

- No person recovering from a communicable disease is permitted to ride in any conveyance without first notifying the owner of the facts. If a person does ride, the owner must disinfect it first before anyone else can ride.

- The same applies to rooms or buildings that are leased. They must be disinfected before they can be leased again.

- Animals with a communicable disease cannot be buried within 500 feet of any residence.

The City of Oil City had a comprehensive list of regulations pertaining to contagious diseases. The city’s 1907 ordinance book outlined what detailed health procedures must be followed.

QUARANTINE

- No child living in a home with a communicable disease can leave to go to school, church or any gathering (public or private), to ride in any vehicle used by the public, to mingle or play with other children. The time limits are: three weeks from onset of chickenpox (or when every scab falls off); six weeks for small pox and scarlet fever.

- The same rules apply to adults.

- The loaning by libraries of any book, paper or periodical to any person sick with a communicable disease or to persons in whose families that has occurred is strictly prohibited for fear of spreading contagion.

- All clothing, bedding and any rooms, including furniture, of a person sick with a communicable disease must be thoroughly disinfected under the supervision of a health officer.

- There shall be no public or church funeral service of any person that has died of a communicable disease. The family of a deceased member must limit attendance to as few persons as possible at any memorial service. The death of any person from a communicable disease shall have the name of that disease that caused the death appear in the public notice.

- In the case of a victim of a communicable disease, the body must be completely enveloped in a sheet thoroughly saturated with a strong solution of bi-chloride of mercury in the appropriate proportion. The body must then be placed in a cotton-lined coffin. Cemetery associations are prohibited to receive bodies unless prepared that way. No body of a person dead from a communicable disease shall ever be exhumed or removed.

One specific ailment drew special attention from health authorities in Oil City during the early 20th century.

Oil City had specific health regulations regarding tuberculosis. Physicians were ordered to report to the city board of health, in writing, the name, age and address of any patient they were treating for TB. The same reporting requirements were levied on any proprietor of a boarding house or hotel in which a tenant was suffering from the disease. Extensive disinfecting measures were to be taken and those included a full fumigation of the dwelling, furniture and other belongings. Penalties included hefty fines and possible jail time.

The Oil City area was served by a facility designed specifically to house and treat individuals diagnosed with TB. It was the Grand View Sanitarium, started in 1904 on the former Folwell Farm in the city’s Hasson Heights neighborhood. The initial project was founded and endowed by oilman S.Y. Ramage and was described across the U.S. as “one of the first sanitariums in the U.S. for the treatment of tuberculosis.” Incorporated in 1905, the facility was “to be used for the purpose of maintaining thereon a hospital for the care and treatment of those suffering from tuberculosis.”

The Grand View Sanitarium opened in the former Folwell Farm in 1904 in what would become Oil City’s Hasson Heights neighborhood.

In 1924, a campaign led by L.H. Gavin of Oil City raised nearly $34,000 to pay off the sanitarium’s indebtedness, improve the property and “carry on the work.”

A newspaper article noted: “This institution is now doing splendid work among those suffering from tuberculosis but more can be helped. Money would make it possible for the institution to accept advanced cases. These constitute a great menace to other people as the danger of contagion is greatest from them.”

A newspaper article noted: “This institution is now doing splendid work among those suffering from tuberculosis but more can be helped. Money would make it possible for the institution to accept advanced cases. These constitute a great menace to other people as the danger of contagion is greatest from them.”

In exhorting the public to chip into the campaign, the news story noted, “You owe it to the patients at this institution and to those who will be admitted in the future. Some of these patients are former servicemen. They contracted tuberculosis as a result of the things they were exposed to during the war. They served us then, now we have the opportunity to serve them and surely we will respond in the manner which these young men deserve.”

In 1943, an acute shortage of nurses due to World War II caused the sanitarium to close its doors. That same year, a proposition was put forth to convert the property, which included dormitories, a lab and an administration building, to the Edith C. Justus Orphans Home. However, that eventually went by the wayside as the county court broke up the Justus Trust “because there is no longer a need for this type of orphans’ home.” The property was eventually purchased by Dr. T.S. Gabreski and changed to a nursing home.

Written by Judy Etzel with research by Kay Dawson and design by Natalie Cubbon.

Donations to the library are appreciated & make this project possible!