Rich and Famous

- Judy Etzel

- February 3, 2023

- Hidden Heritage

- 8641

Many Oil City residents earned high recognition as well as enormous wealth. Others, meanwhile, have shared ties with those individuals who had both fame and money.

The relationships included leading U.S. businessmen, company founders, and philanthropists.

Here’s a quick look at some of those brushes with fame and fortune:

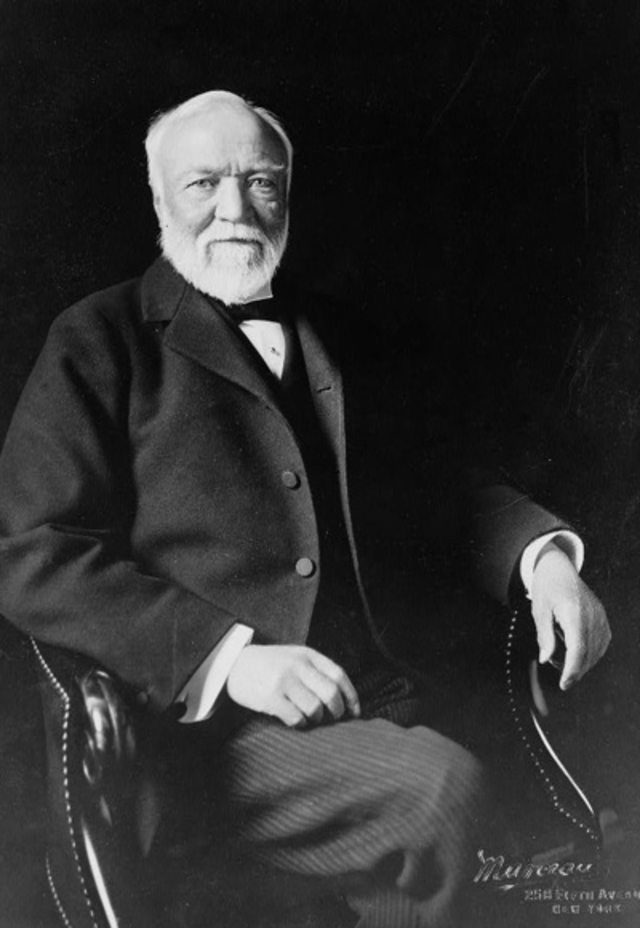

Andrew Carnegie

In 1900, public library enthusiasts, including the Belles Lettres Club members, were eager to establish a free-standing library in Oil City. The club formally asked steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie of Pittsburgh for assistance.

Carnegie, then in the process of helping fund public library projects across the U.S., agreed to help and donated $44,000 to help build a library in Oil City. Additional money was raised and construction began in 1902.

The Carnegie Library, later renamed the Oil City Public Library, opened on July 6, 1904.

In the process of sealing the Oil City Library deal, Carnegie met at one time or another with Belles Lettres Club members. He had a previous connection to the area, too, as he was listed as the largest stockholder of the Columbia Oil Co. in Rouseville in 1861.

Frank J. Mooney

Las Vegas, Nevada, legalized gambling in 1931 and, as the industry grew, a local man played a key part in that business.

Frank Joseph Mooney, born in Oil City in 1909, worked as a messenger for the National Transit Pump and Machine Co. on Main Street. He eventually was promoted to assistant controller at the plant.

In 1952, he moved to Las Vegas and was hired as an accountant for the Sands Hotel. Over the next several years, Mooney served as secretary-treasurer for the parent company that owned the Alladin, Stardust, Fremont and Hacienda hotels and casinos until he retired in 1979.

In that time, he served as a member of a special task force under Gov. Paul Laxalt that helped establish new Nevada gaming regulations. He died at the age of 83 in Las Vegas in 1993.

Rollin Rice Richardson

A local man who made a fortune in the oil industry eventually turned it into a lucrative mining company and cattle-raising business in Arizona.

Rollin Rice Richardson, born in 1846 in Shippenville, was the son of a pioneer crude oil buyer at the Tarr Farm. The elder Richardson was in partnership with William Hasson of Oil City.

Rollin, who served as a colonel in the Union Army during the Civil War, returned home and made even more money in the oil fields.

In 1880, Rollin sold his oil interests for $200,000 and migrated to Arizona to engage in raising cattle. He soon became the owner of the biggest ranch in Arizona.

A drought in 1893 wiped out his herd and forced Rollin to find another business venture. He founded the Three R Mine which shipped high-grade copper, as well as some gold and silver, to several smelters. It became one of the most profitable mining businesses in the U.S.

The area around his mine quickly filled with residents and Rollin decided to organize the community in 1896. At first called “Rollin” in his honor, the town was later changed to “Patagonia” in tribute to the nearby hills that were called by that name. It is located in Santa Cruz County.

The Three R Mine grew even bigger and Rollin began searching for more mining equipment. He reportedly offered a Franklin citizen one-third interest in his company for $20,000. The buy-in offer was declined, so Richardson sold the entire mineral claim for $550,000 in cash in 1913. To celebrate his big sale, his sister, Mrs. O.D. Bleakley of Franklin, visited him in Arizona.

“It is one more example in a splendid list of Venango County boys who have hit the trail leading to achievement and reward,” noted the local newspaper in learning of the sale.

Rollin, who died in 1923 in Arizona, is buried in the Franklin Cemetery.

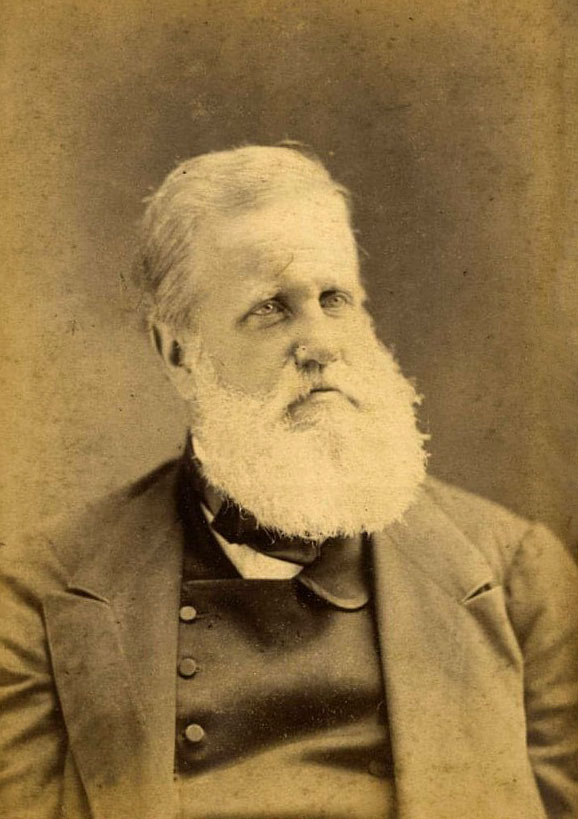

Emperor Dom Pedro

Dom Pedro d’Alcantara, Emperor of Brazil, arrived on a special train in Oil City on May 6, 1876.

The emperor, the guest of oilman John J. Vandergrift of Colbert Avenue, came to the city to tour the Oil Region. On hand to greet him was Andrew Cone, a local resident who had recently been named U.S. Consul to Para, Brazil.

Dom Pedro was described by the local newspaper reporter as being a man between the ages of 55 and 60 years, of medium height and build, light complexion, large blue eyes, long white hair and whiskers. He was wearing a white hat.

Horse-drawn carriages pulled up to the train depot to transport the guest and others to the Imperial Works refinery at Siverlyville. In the first carriage were the emperor, who carried with him a book on petroleum that he said he had been studying, Cone and a Derrick newspaper reporter. The book may have been an edition of “Petrolia,” written in 1870 by Cone and Walter R. Johns.

A second carriage accommodated local officials, as well as a reporter from the New York World newspaper.

Many years later, one observer, local resident Isabel Kuhns, recalled the visit. She and her family lived a few doors down from the Vandergrift home on Colbert Avenue. She said she and other children went out to the curb to see the emperor pass by in his carriage.

“He was a fine looking man and so gracious. When he saw us peering at him, he stood up in the carriage and took off his big white hat to us and bowed deeply,” she told a reporter.

The Imperial Refinery was at the time considered the largest inland refinery in the world.

At the refinery, company officials took him on a tour through the plant and explained the petroleum refining process. They then walked a short way to watch an oil well being drilled. An adjacent pasture filled with grazing cows also caught the emperor’s attention and he went over to inspect them.

Back at the refinery office, Dom Pedro was shown oil specimens taken at various stages of refining. He was presented with small samples to take home.

Enroute back to the station, the emperor and his official party stopped briefly at the Cone residence and then proceeded to Palace Hill to see some producing oil wells.

A large crowd awaited him at the railroad station. Frank Robbins, photographer, gave the emperor a set of stereoscopic views of the Oil Valley.

According to newspaper accounts, Dom Pedro’s special train consisted of an engine and a personal coach which he had bought in New York to use in his U.S. tour and then take back to Brazil.

Leaving Oil City, the train traveled through Parker, stopped briefly at Foxburg and then continued on to Philadelphia so he could attend the Centennial Exposition.

The emperor’s train did not stop at Pittsburgh and that drew an observance from local newspapers:

“Pittsburg(h) feels bad. The Emperor gave the place what they consider the ‘dirty shake’ and proceeded forthwith to the more congenial clime of Oil City … The general impression among all was that the action of the Emperor savored very much giving Oil City the cream and Pittsburg(h) the skim milk.”

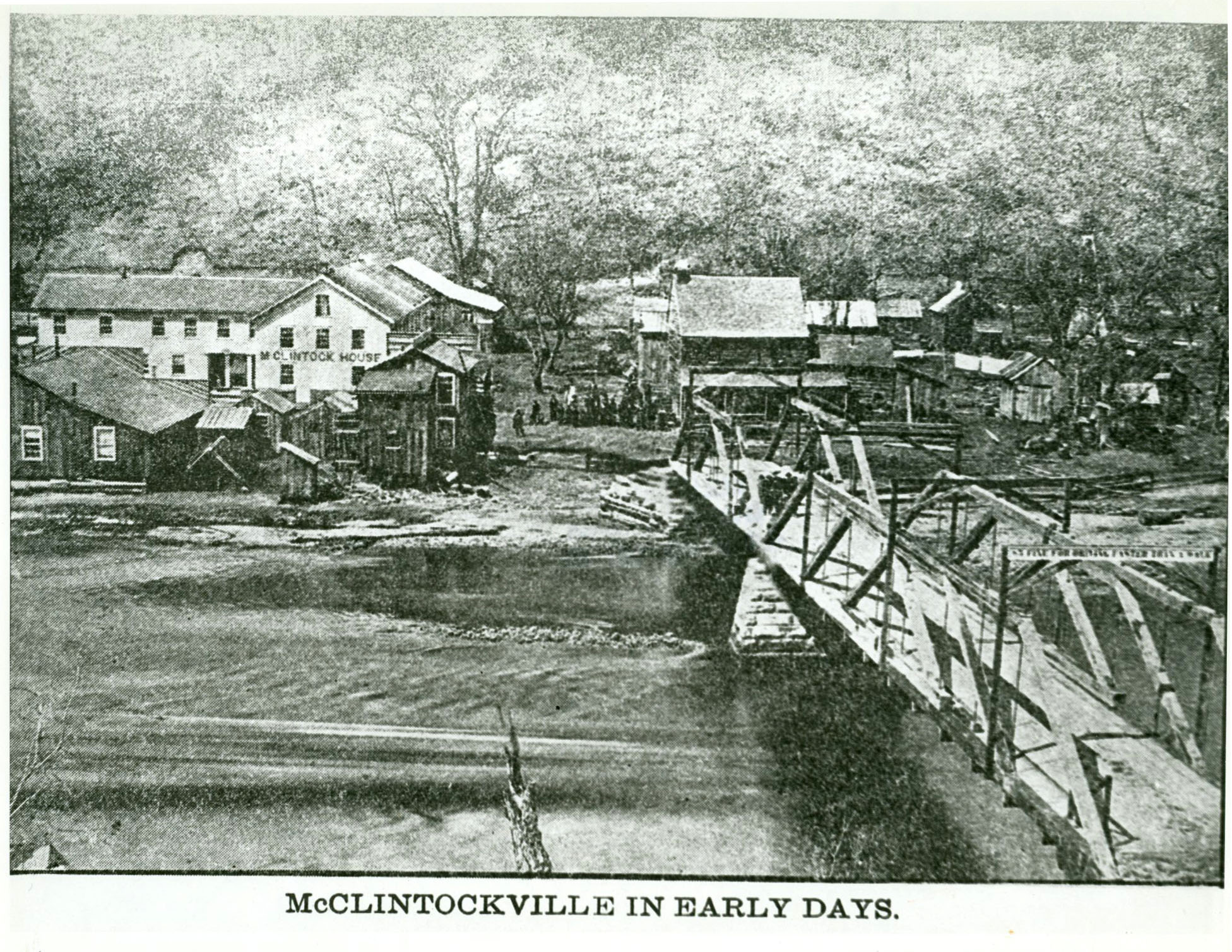

John Washington Steele

Born in 1843, John W. Steele became an orphan as a young child and was adopted by Culbertson and Sarah McClintock of Rouseville.

Later known as Coal Oil Johnny, Steele would become one of the world’s first get-rich-fast oil millionaires. He would also be known as a prime example of a riches-to-rags saga.

In 1859, Sarah McClintock, by then a widow, leased her property to oil speculators roaming the valley soon after Col. Drake’s successful well near Titusville.

When she died as a result of injuries from a fire only a few years later, young Johnny inherited the McClintock farm and the lucrative oil leases. He became very wealthy almost overnight.

In 1864, Steele moved to Philadelphia, leaving his wife and young son in Oil City, and began spending lavishly.

Dubbed “the oil prince” by newspapers following his exploits, Steele was believed to be making, and spending, about $2,000 a day that was earned from his oil-related holdings.

His fortune was soon squandered and he was forced to return to his family in Oil City. In 1867, he filed for bankruptcy which ended a host of lawsuits filed against him for failure to pay his debts.

Steele took on odd jobs for the next several years. He died in Nebraska in 1920.

DID YOU KNOW?

The Venango County Genealogical Club ran this item in one of its monthly newsletters:

The following appeared in the Oil City Semi-Weekly Derrick on Sept. 9, 1904.

FRANKLIN – A curiosity in the way of an instrument of conveyance was filed for record in the office of Register and Recorder Buchanan on Monday, Sept. 5. The property transferred is nothing more or less than a human being – the son of the party of the first part.

The instrument is an ordinary quit-claim deed and is from E.A. Albaugh of Hickory Township, Forest County, to J. George Schmidt of nearby Pleasantville.

The deed conveys Mr. Albaugh’s “right, title and interest as father in my son Clifford Albaugh, born March 13, 1900, whose mother is now dead, to the said J. George Schmidt, to be hereafter his adopted son and heir.”

It further set forth that “the said J. George Schmidt is to care and provide for the said Clifford Albaugh, to be known as Clifford Albaugh Schmidt, as his own son, to clothe and give him a home and send him to school, according to law, and do for him, in all things, as a father should and is by established usage and common kindness in such cases expected to be done.”

The “valuable considerations” for which the transfer is made are not given.

The deed was received by Mr. Buchanan by mail last week. That official recognized its invalidity and wrote to Squire Hume informing him of the fact and suggesting that the child be adopted in the regular way but Mr. Hume replied that Mr. Schmidt insisted that the deed be filed.

Written by Judy Etzel with research by Kay Dawson and design by Natalie Cubbon.

HIDDEN HERITAGE IS SPONSORED BY:

Jack Eckert & Susan Hahn

— In Memory of Kay Ensle —

Support This Project

Donations to the library are appreciated to help offset printing costs & make this project possible! Want to become a sponsor? Email us at promotions@oilregionlibraries.org to get started!

Make a Donation