So You’ve Landed a Headquarters Job…

- Judy Etzel

- March 3, 2023

- Hidden Heritage

- 9848

Oil City was in the national news on April 10, 1984, and the local reaction was anything but positive. The page one story was in the prestigious Wall Street Journal newspaper and was titled “So You’ve Landed A Headquarters Job? Don’t Smile So Fast.”

Susan Carey, a staff reporter for the Journal, a daily newspaper with the largest circulation in the U.S. at that time, wrote about the tribulations facing top Fortune 500 company executives assigned to small, out of-the-way towns.

While referring to a few other large companies that had their headquarters in small communities, Carey specifically focused on Quaker State Oil Co. and Oil City. The article began with a quote from a Quaker State advertising executive, one of several top managers who have been recently assigned to the company’s headquarters in Oil City.

“Oil City is great if you like beer and four-wheel-drive trucks and cliquish natives,” said Tom Neil, a Pittsburgh transplant who complained that no one ever invited him to a party and rumors spread that he, owner of a large house and sporty car, might be a narcotics agent.

While acknowledging that “working at a corporate headquarters is the dream of many ambitious managers and executives,” Carey pointed out the lifestyle change can be dramatic if the move is from a metro area to a small town.

“Oil City is particularly isolated … it is two hours from Pittsburgh and a long hour from Erie and Youngstown, neither of which is regarded as a center of culture and entertainment.”

The wife of one Quaker State executive complained about the lack of restaurants, shops and things to do while a company public relations manager, who was divorced, found limited “opportunities for romance” in Oil City.

Carey wrote that many of the 300-plus corporate employees grew up in Oil City and enjoyed the community. “It is neighborly, good for raising children, set in idyllic countryside and full of real estate bargains,” she wrote.

After briefly citing the earlier successes in Oil City, Carey noted the petroleum industry soon relocated to Texas and Oklahoma and that resulted in a further shrinking of local companies that supported the oil business.

One older Quaker State executive said the transition to small-town life can be difficult for younger singles and couples. “If I were young and single, I wouldn’t be caught within 10,000 miles of here,” he said.

The Dramatic Outcry

The response from the community about the Journal’s depiction of Oil City was swift and brutal. The Journal was sold out within 30 minutes at McNerney’s in downtown Oil City and the topic was discussed at lunch counters, offices, and street corners nearly non-stop all day. Relatives and friends across the U.S. called back home to comment on the story.

U.S. Congressman Bill Clinger of Warren hit back first, noting, “If it were not for places like Oil City in the last century, there would be little need for organizations like Dow Jones and Co. (owner of the Wall Street Journal) in the present century.

“Your story did a good job of belittling Oil City … and its people,” Clinger wrote to the Journal. “I think your attitude that small communities spawn small minds and boring lifestyles is unfair.”

Small towns, he said, produce in many cases “our greatest war heroes, inventors, discoverers, educators, corporate giants, religious leaders.”

Joe Barr, former Oil City manager and then vice president of the city’s Economic Development Corp., called the Journal editor to “review the article and to consider what should be done about it.”

While cautioning that city residents not respond to the article in the same “deflating and dispiriting tones of the article,” Barr said, “But, a response must and surely will be made in measured terms of the community’s self-confidence and a generous spirit toward the aberrant Wall Street Journal reporter.”

Ron Black, executive director of the Oil City Area Chamber of Commerce, said he chose to live and work in Oil City and added, “And the other people who come here will grow to like it – beer drinking, four-wheel drive trucks and all.”

Oil City Mayor Leonard Abate hit back, too, and said the Journal’s front page story “can do harm to the efforts of all those who have worked so hard to promote the economic well-being of the city.” He also rapped some Quaker State employees who were quoted and said “they should have had the intelligence and discretion to keep their personal opinions to themselves.”

The public relations manager at Quaker State said he didn’t believe the Journal writer was “looking to knock Oil City” but rather to call attention to the difficulties of moving from a large city to a small town.

As for the oil company, a prepared statement in reaction to the story was “The company regards Oil City as the best place in the world to be.”

Local newspaper columnist Ed Sehon, who with his family had lived in Oil City for two years, said living here was “special.” Sehon wrote, “The superb educational opportunities, the distinctive neighborhoods, the strong work ethic, the parks and recreational facilities, the churches and the charities combine to make our community a place where young people can grow up, middle-agers can grow comfortable and senior citizens can grow closer together.

“If you are one of those who choked at the Journal article, don’t feel ashamed. It was merely your sense of civic pride getting caught in your throat.”

Steve Szalewic, a local writer, said the Journal story didn’t upset him because “I’m a small-town dandy, born and raised in the shade of Hogback Hill.” He wrote that small town living offers him readily accessible golf courses and trout streams, no traffic jams, no worries about walking through town at night, a doctor and dentist who are friends, immediate home and related repairs, ample hunting opportunities, a garden and more.

“And as for operas and other so-called social distinctions (the lack of which was lamented by the company executives), the ‘fat lady’ had not sung of Oil City’s demise yet,” he wrote.

Carolee Michener, editor of The News-Herald newspaper in Franklin, described the Journal story as “single-dimensional” because it did not “offer any quotes from families who have made the transition from large cities to a smaller community and are happy with the change. … There is no effort to balance the criticism with any positive reaction from some satisfied workers and their spouses.”

Backlash is Fierce

The chatter continued and the area media was bombarded with letters and interviews objecting to the Journal story. T.G. Williams of Oil City wrote “the article was not news, it had no bearing on the national economy, it proved nothing and improved nothing – it only hurt and embarrassed a lot of pretty fine people and caused immeasurable damage to a proud community.”

Kenneth Miller of Seneca wrote, “I would like to see Oil City accept this threat on her character as a challenge to show her true colors – let’s stand tall, help promote her and strive to be more outwardly friendly.”

Noting the article was “a slap in our face,” Tim Thompson wrote, “…Despite all the setbacks we’ve suffered, let it not be said that our pride in our community has been tarnished in the least.”

Richard Cotter of Franklin noted, “If you find you don’t like our situation, change it. Get involved in your community, get involved in your job, get involved in your family, or get out.”

T. Gray of Oil City suggested, “If you don’t like this type of living then perhaps you had better ask for a transfer” and added, “By the way, I don’t drink beer or own a four-wheel drive truck – I prefer 7 and 7’s and Grand Prixs.”

Lee Caplan, who had recently been hired as general manager of Brody’s apparel store and had turned down a similar position at a much larger store in Boston, wrote that his experience in moving to Oil City has “revolved around intelligent and warm people.”

James McGrath, a resident of New England who moved to Franklin, wrote, “In New England, it was assumed that if you were a nice person, sooner or later you’d prove it. Here, I was astonished to learn that you are given the benefit of the doubt. Almost everyone is accepted, warmly and evenly. We were and I don’t even own a four-wheeler.”

“I’m fairly certain that Russian intelligence translates each edition of the Journal. … They probably conclude that Oil City, Pa., isn’t worth a bomb. At least I hope so. Thanks, Quaker State,” wrote Tony Bianchi of Franklin.

Jean Marvin of Tionesta wrote, “These men have my sympathy and should indeed be pitied. Life is so brief and to have to live it in such misery is truly a shame.”

And in what has been a premonition, West Hickory resident William Bossert wrote, “The Journal article looks like an inside job from one or ones at Quaker State. Is Oil City being conditioned for a corporate headquarters move?”

Living in the ‘Boondocks’

It didn’t take long at all for another bombshell quote to spawn a whole new public reaction.

Within a few days of the Journal publication, Carey was interviewed by The Derrick and said she wanted “to write a light, enjoyable, humorous feature story about something we all joke about – living in the boondocks. I thought it was rather harmless.”

The Oil City Junior High School immediately stepped up and scheduled “Boondock Day” on April 13. Organized by teacher Barbara Smutek, the event was to be “a fun day” as students and faculty were encouraged to dress as “rednecks”. There were school parking slots blocked off especially for four-wheel drive vehicles.

An assembly to choose a student as Boondocker of the Year was held with the award including a case of soft drinks, a t-shirt, and “crown of straw.” There would also be displays throughout the school.

Smutek’s students were assigned to write a composition on why Oil City is a nice community in which to live. Teachers wrote a “special menu” for the day that featured dandelion greens, puree of possum, venison steaks and squirrel pie. Chris Emanuele won the Boondocker of the Year costume award.

Another Article

Oil City was featured in another national news story just days after the Wall Street Journal article.

The National Geographic Society distributed a report to the media in mid-April 1984 about unusual newspaper names. The Oil City-based Derrick newspaper was listed as one of only a few U.S. newspapers that had names that were unusual and different.

“Some newspapers get their unusual names from the industry of their hometowns,” noted the article. “These include the Oil City (Pa.) Derrick, the Hereford (Texas) Brand and the Crystal Falls (Michigan) Diamond Drill.

The Derrick, a newspaper that marked its 150th anniversary in 2021, was also known as the Organ of Oil because of its extensive, first-hand reporting on the early petroleum industry.

A Muddy Mess

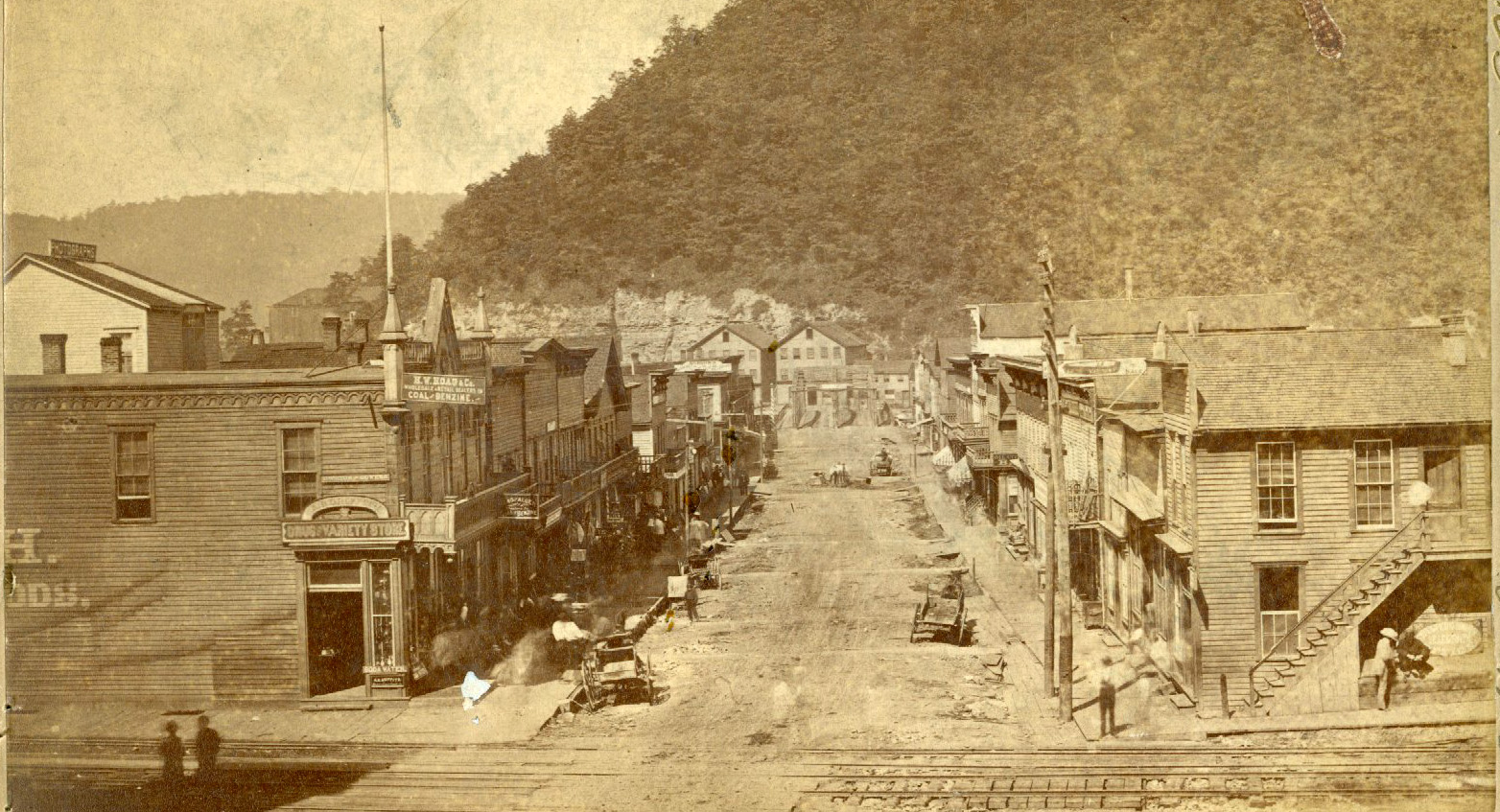

In its early days, Oil City was a vibrant, bustling and expansive community. It was also a muddy mess where shanties, oil derricks and old river barges were in profusion throughout some parts of town. That was evident even as entrepreneurs in the oil industry as well as those in supporting industries were making barrels of money.

In December 1864, a mere five years since the petroleum industry was launched near Titusville, a writer for the Philadelphia Press newspaper wrote this:

“How can I describe this place? Do you imagine a city of banks and highways, and dwellings, and rushing men and women eager to be rich, a city of chestnut trees and Broadways and Pennsylvania avenues?”

“If so, abandon the idea, for Oil City is nothing more than a long, narrow mud flat that seems to sprawl at the feet of high shale rocks. … It lives in newspapers as a city and as a habitation for men but is nothing more than a collection of houses, low-roofed, dirty shanties, hastily put up, without much regard to cold and rain.”

“A city of hotels and offices, filled with booted, muddy, heavily-clad men, surrounded by tall derricks that look like the shipping yards of New York or Philadelphia.”

The city, wrote the newspaper reporter, appears as “a nest of moles burrowing in the mud.”

“If you wish to live in mud, to walk in mud, ride in mud, to see nothing but mud, to have the color of your clothing obscured by mud, to inhale nothing but an air burdened with gas and petroleum, and to see what a livid, hungry, anxious genus animal of men are when they are bitten by this money-setting tarantula, by all means, come to Oil City.”

In that same time period of the winter of 1864, J.H.A. Bone, a writer for the Cleveland Herald, visited Oil City and described the community as “worthy of its name.”

“Oil City, with its one long, crooked and bottomless street; Oil City, with its dirty houses, greasy plank sidewalks and fathomless mud; Oil City, where horsemen ford the street in from four to five feet of liquid filth and where the inhabitants wear knee boots as part of indoor equipment.”

“Oil City … the air reeks with oil. The mud is oily. The rocks hugged by the narrow street perspire oil. The water shines with the rainbow hues of oil. Oil boats, loaded with oil, throng the oily stream and oily men with oily hands fasten oily ropes around oily snubbing posts.

Still, wrote Bone, “everything at Oil City is bustle and confusion. As many people are in the principal street as frequent Third Street in Philadelphia.”

Written by Judy Etzel with research by Kay Dawson and design by Natalie Cubbon.

HIDDEN HERITAGE IS SPONSORED BY:

Jack Eckert & Susan Hahn

— In Memory of Carole Eckert —

Support This Project

Donations to the library are appreciated to help offset printing costs & make this project possible! Want to become a sponsor? Email us at promotions@oilregionlibraries.org to get started!

Make a Donation