The Glass Industry

- Judy Etzel

- September 2, 2022

- Hidden Heritage

- 6154

Oil and gas fueled Oil City’s early economy. The extraction, production and refining processes prompted an array of other industries such as those that specialized in drilling equipment, pumps, barrels and much more.

There was another business, though, that helped prime the city’s economic fortunes and that was the glass industry. It was a big time enterprise from the 1930s through the mid-1980s when hundreds of local residents worked in the glass plants.

In 1929, the Oil City Chamber of Commerce launched an intense effort to lure a glass manufacturing concern to the city. The lobbying effort focused on what the city could offer: a hefty labor market, excellent railroad transportation access, modern power facilities, prime banking facilities and “a friendly, co-operative spirit towards incoming industries,” boasted the chamber.

The business organization raised $100,000 in capital stock, all subscribed to by local residents, to help promote the project. Leon Gavin, president of the chamber, and R.R. Underwood, president of the booming Knox Glass Bottle Co., labored to seal the deal.

The Plant is Built

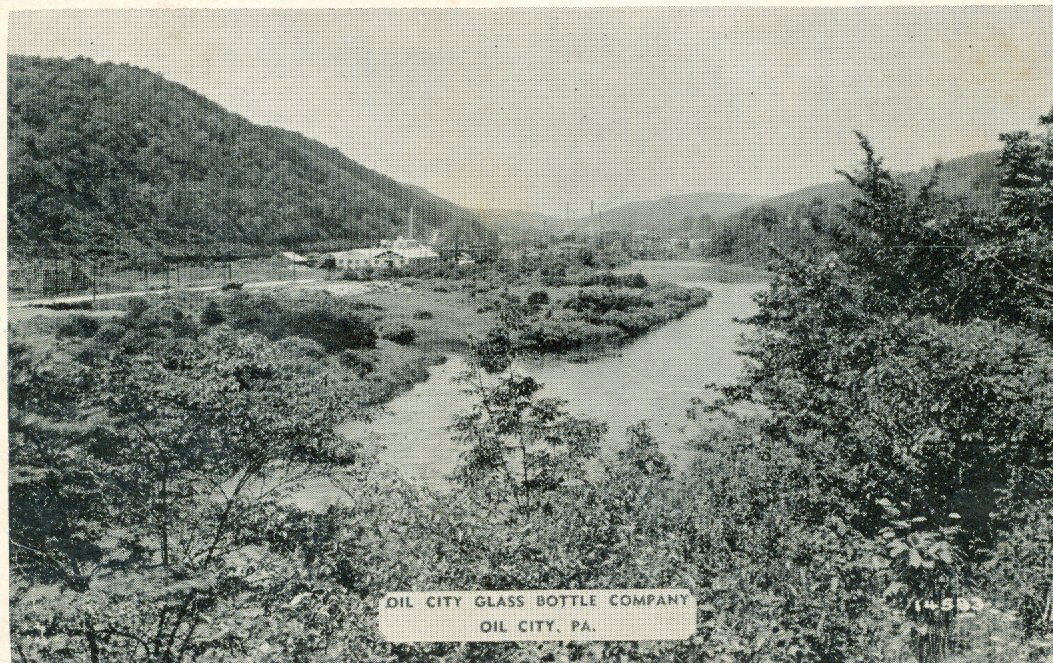

Construction of a modern glass plant began on a two-acre tract near Manion Steel Barrel on the Oil City-Rouseville Road.

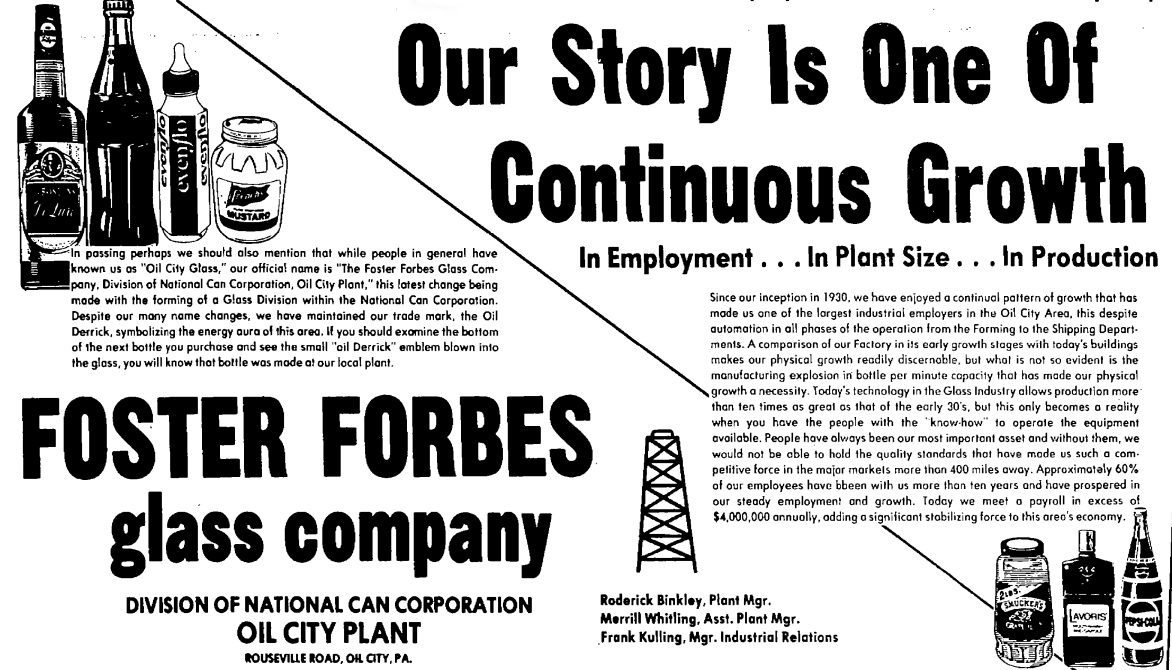

On Sept. 30, 1930, the new manufacturing facility opened with a workforce of 60 people. The plant, known as the Oil City Glass Bottle Corporation, was part of the Knox Glass Bottle Co. The new company boasted an oil derrick as its trademark logo.

The Oil City plant prospered and listed gross sales of $830,508.50 for 1936.

Its specialty glass bottles were prescription and soda bottles. Later on, the company expanded and began producing glass containers for Pennzoil outboard motor oil, Air-Wick deodorizers, French’s mustard bottles, Pepsi bottles and more.

According to information in the “Venango County 2000 – The Changing Scene” book, the Oil City plant was “in 1952 the sole supplier of the world-famous Evenflo nursing bottle.”

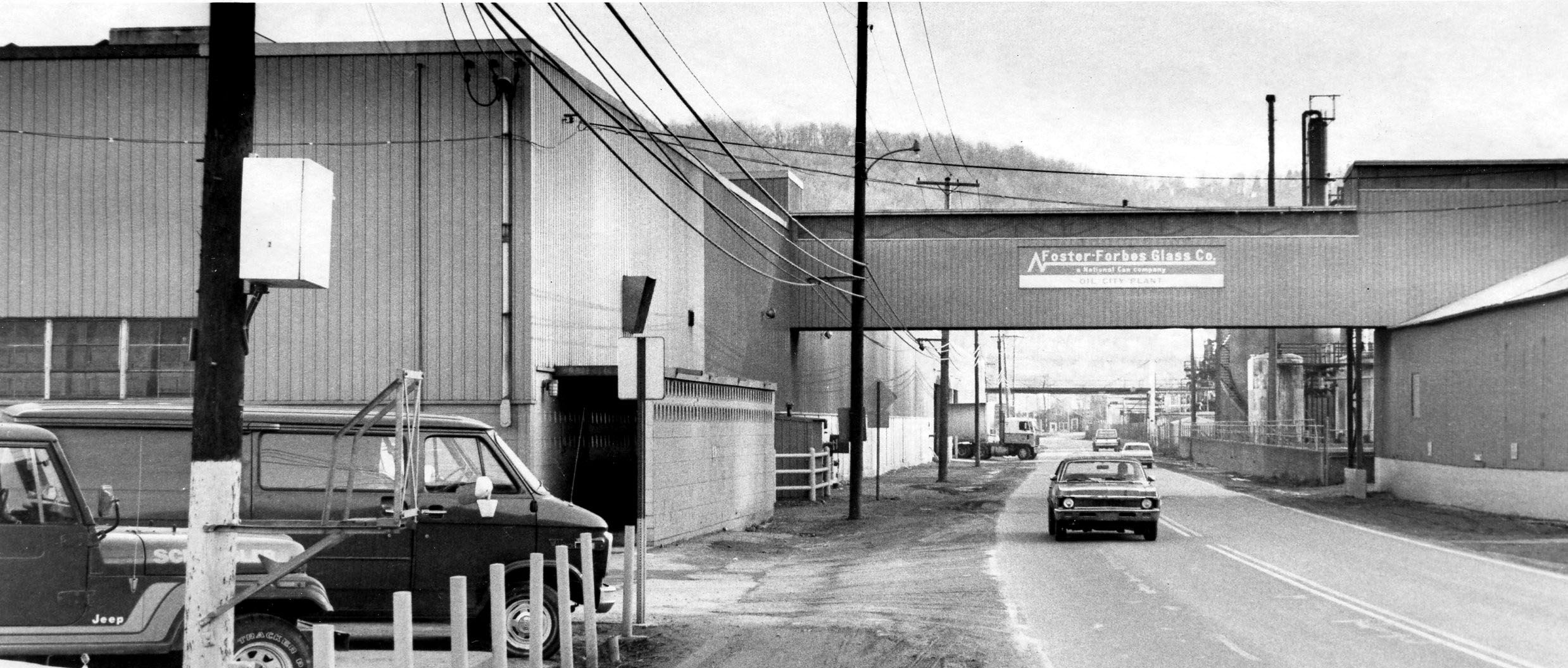

That same year, the business name was changed to the Oil City Glass Company. It was bought by Pyramid Rubber Co., which would later merge with Questor Corp. The new owners installed an electric melt furnace and built a sprawling warehouse. Two warehouses were built and they were connected across Route 8 by an elevated conveyor belt. Employment rose to 250 with all but a few represented by the Glass Bottle Blowers Association Local 123. Dean B. Hunt served as general manager and president of the Oil City Glass Co. plant in the 1960s.

Employment Hits 450

In 1969, the National Can Corp. bought the local plant and merged it into its Foster-Forbes glass division. More than $1.5 million was invested in modernizing the plant. Sales continued to grow and employment grew to 450 workers by 1972.

In that period, the newly named Foster-Forbes plant began a glass recycling project focused on cutting back on litter and solid waste problems. Donors would be paid a penny per pound for their empty glass bottles and jars. The public responded and, at the end of three years, the company had taken in 3,350 tons of glass, the equivalent of about 13.5 million bottles, for reclamation.

The local glass plant continued to thrive. About five railroad cars a day shuttled raw materials to the site. That material was then manufactured into 20 truckloads and eight boxcars filled with finished glass containers. According to the company’s 1972 annual report, the plant, operating at 24 hours a day and seven days a week, was manufacturing 3.5 million finished glass containers every year. The products ranged from whiskey bottles to jelly jars.

The sizes varied from small perfume bottles to half-gallon beverage jugs. The plant also made its own paper cartons for shipping. In the following years, a truckers’ strike and modernization affected the plant’s workforce but the number still remained high.

Bad Times Ahead

In 1977, about 431 employees were on the job and that made the Foster-Forbes plant one of the area’s largest employers. The crew was putting out about 750,000 glass bottles and jars a day. Trouble began in the early 1980s as glass inventories built up in reaction to a surge in the plastic container industry. Fuel costs were up and equipment was outdated, too. Still, the Oil City glass plant continued to produce and was honored by its parent company for “exceptional production standards.” Average annual wages were between $26,000 and $35,000, according to the plant’s 1982 spreadsheet. The 1982 annual payroll exceeded $5 million. However, furloughs began and continued through 1983.

On Feb. 22, 1984, the National Can Corp. announced it would close its glass manufacturing plant in Oil City. The shutdown affected 225 people still on the job and another 125 who had been furloughed just two months earlier.

The news came just weeks after Oil Well Supply, another major local employer, announced it would shut down. It also coincided with similar glass plant shutdowns – Glass Containers Corp. plants in Marienville and Parker, both in 1982. The Oil City plant closing, said the company, was the result of reduced production volume due to “inroads by other packagers (plastic), obsolescent furnace capability and distance from high-volume demand sources.” Renovations to update the plant were estimated at between $7 million and $9 million, a cost that was further complicated because of high trucking costs, escalating prices for natural gas that powered the plant, and lack of room to expand the plant.

The plant closed April 13, 1984. Despite intense civic efforts, no buyers were found and the plant was demolished a few years later.

Glassylvania

A second smaller but very distinctive glass business carved out an original niche in Oil City. It was Glassylvania Co., located in the former Saltzmann Brewery building at Union and Charlton streets on Oil City’s North Side.

Founded in 1928, the company was organized by Archie Steck and Richard Fry. The company specialized in decorative glasses, mugs, ashtrays, plates, ice containers, paperweights and more. It did not manufacture the glass but offered a silk-screen painting process that customized the glassware with logos, mascots and more.

The customers were corporations, tourist agencies and universities and colleges. The designs were imprinted on the glassware which was then fired and baked. The customer lists included hundreds of companies as well as universities eager to have their own promotional materials. One key customer base involved groups having high school or college reunions. Later owners were Sheldon and Barry Lang, brothers, and husband-and-wife team Tom and Cathy Daugherty.

The business closed several years ago.

Written by Judy Etzel with research by Kay Dawson and design by Natalie Cubbon.

HIDDEN HERITAGE IS SPONSORED BY:

Oil Region Alliance

Gates & Burns Realty

Support This Project

Donations to the library are appreciated to help offset printing costs & make this project possible! Want to become a sponsor? Email us at promotions@oilregionlibraries.org to get started!

Make a Donation