The Oil Exchange & National Transit

- Judy Etzel

- September 30, 2022

- Hidden Heritage

- 9314

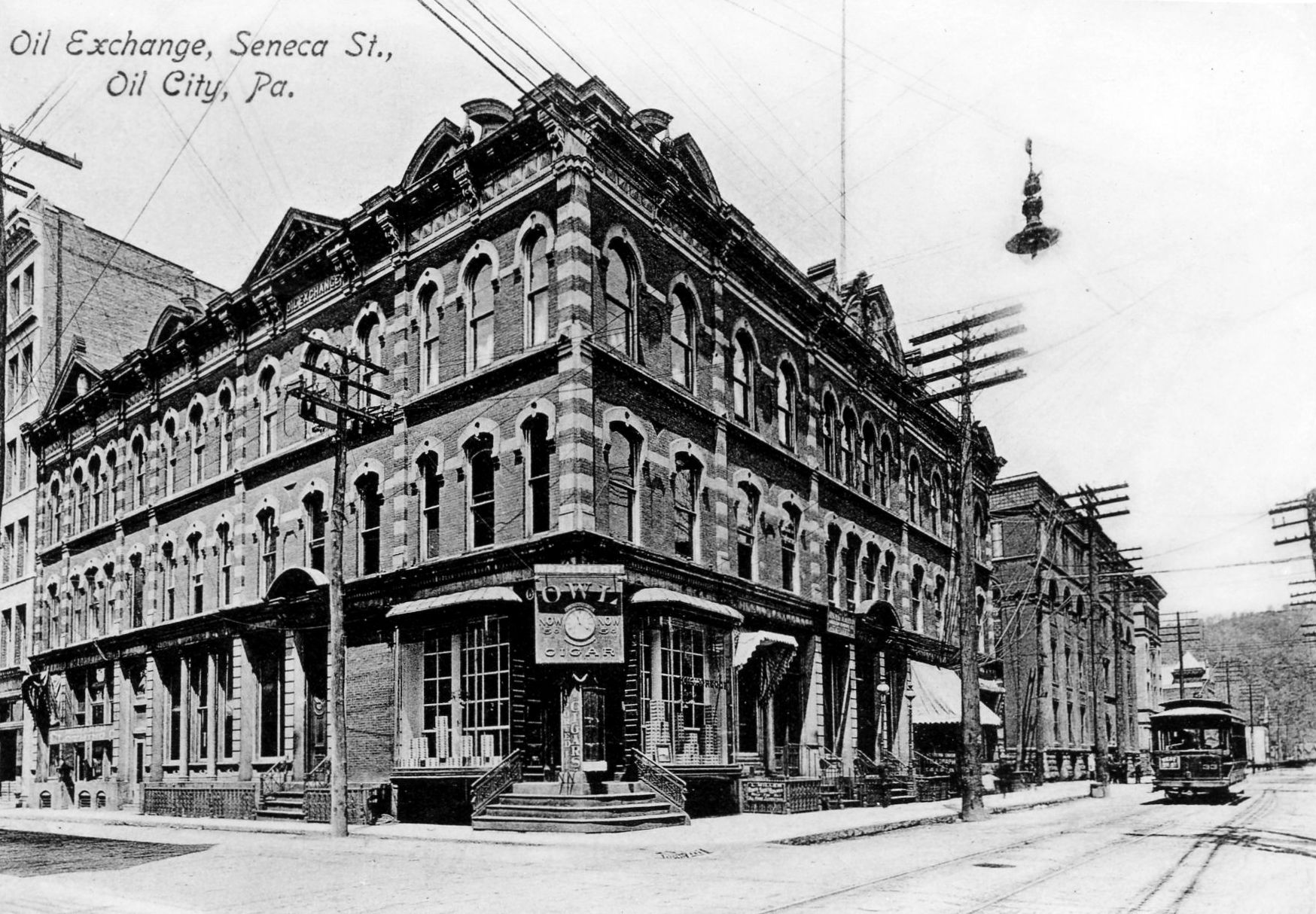

Two of Oil City’s most imposing and unique buildings once stood opposite each other in the city’s North Side business district.

The towering structures – the Oil City Oil Exchange and the National Transit Building – were a testament to the city’s immense wealth created by the early oil industry. The two enterprises gave considerable heft to the city’s claim as the Hub of Oil for the entire nation.

The Oil Exchange

When the petroleum industry was launched with Col. Edwin Drake’s successful oil well in 1859 near Titusville, speculators sold and purchased crude oil in informal settings.

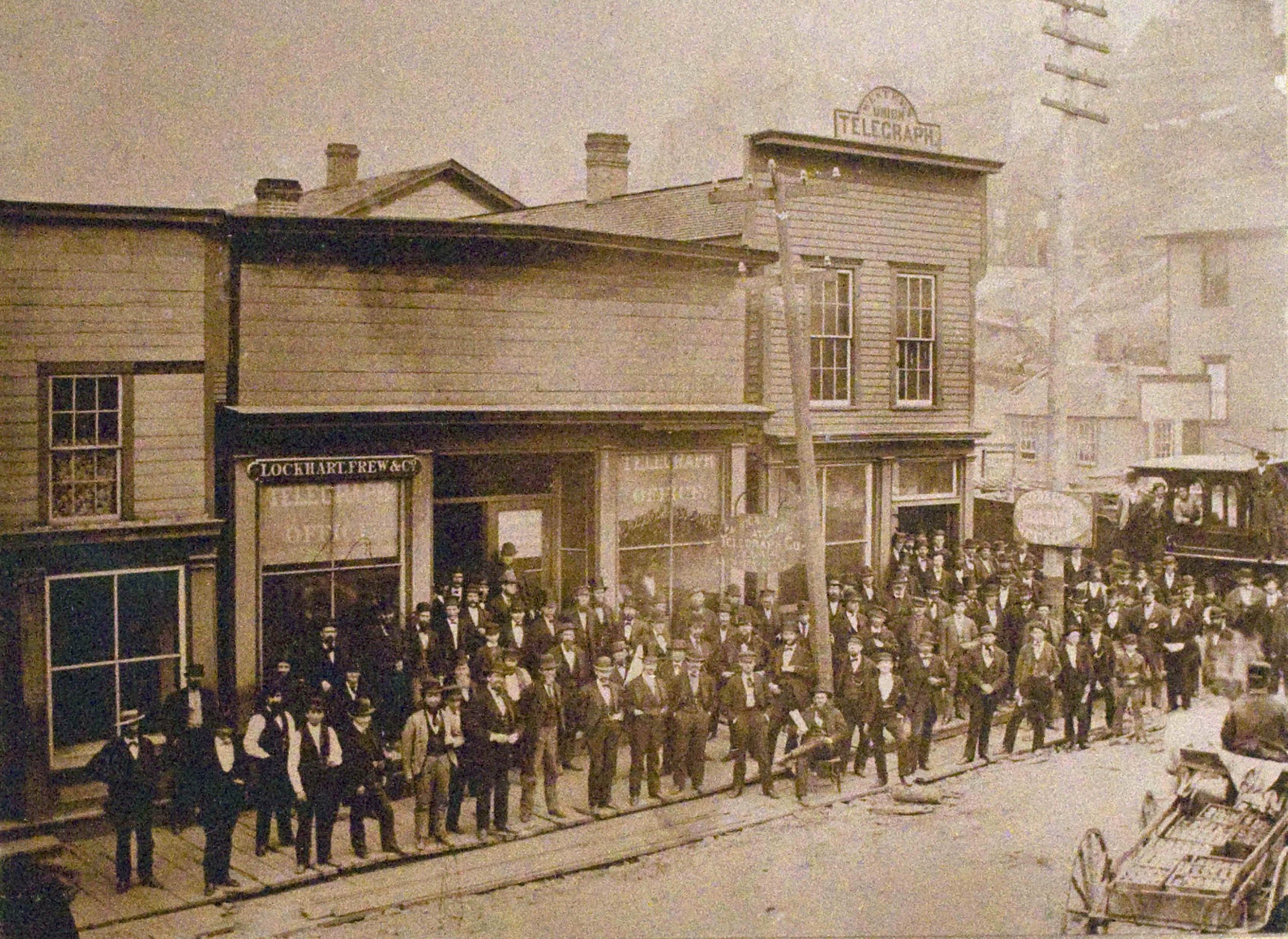

The headquarters of the oil men, according to one early report, was “in the saddle” until oil boomtowns offered curbstone exchanges, or the city street corners where groups of oil men gathered.

Soon, a custom-designed railroad car designed to be an oil exchange was added to the Oil Creek Railway. There were 13 daily stops between Titusville and Oil City and trading was informal and done on the honor system with no buy/sell certificates offered. One newspaper account noted that although informal, the trading was fair: “The word of an oil man is considered as good as his bond and, it may be added, there are yet many of this class in the oil country, though of course there are some black sheep – or bulls and bears.”

As the industry quickly grew, an oil exchange office was set up in the Collins House, later the Arlington Hotel, in Oil City. That led to an intense push to build a structure specifically to house an oil exchange. A more formal location to conduct oil business was necessary, insisted many involved in the oil trade, due to the expanding industry – daily oil transactions by 1874 averaged 10 to 14 million barrels of oil. The bulk of the U.S. production was in the Oil Valley.

In April 1874, a group of Oil City-based oil men received a charter from the state to organize an Oil City Oil Exchange. Construction started in July 1877 on a large lot at the corner of Center and Seneca streets. Members of the building committee – William Hasson, A.J. Greenfield, William Parker and John Mawhinney – chose J. M Budge of Meadville as the architect. He had also designed the nearby Derrick newspaper building along Oil Creek.

The three-story building, described as substantial and sturdy and constructed at a cost of $65,000, was owned by the 400 members of the Oil Exchange. It opened in April 1878 and was lauded by the local newspaper as “the largest and most elaborate structure ever erected in the Oil Region and fairly represents the magnitude which the speculative part of the petroleum trade has attained … the new Exchange is a source of much pride.”

The building, constructed in “the modern style of architecture, unadorned with gingerbread work”, was brick with stone trimming and iron cornices. Inscribed overhead was “Oil City Oil Exchange” and carved stone oil barrels were installed along the roofline. There were iron stairways at several entrances and lamp posts with gas lights at each entry. The building was surrounded with a decorative iron railing.

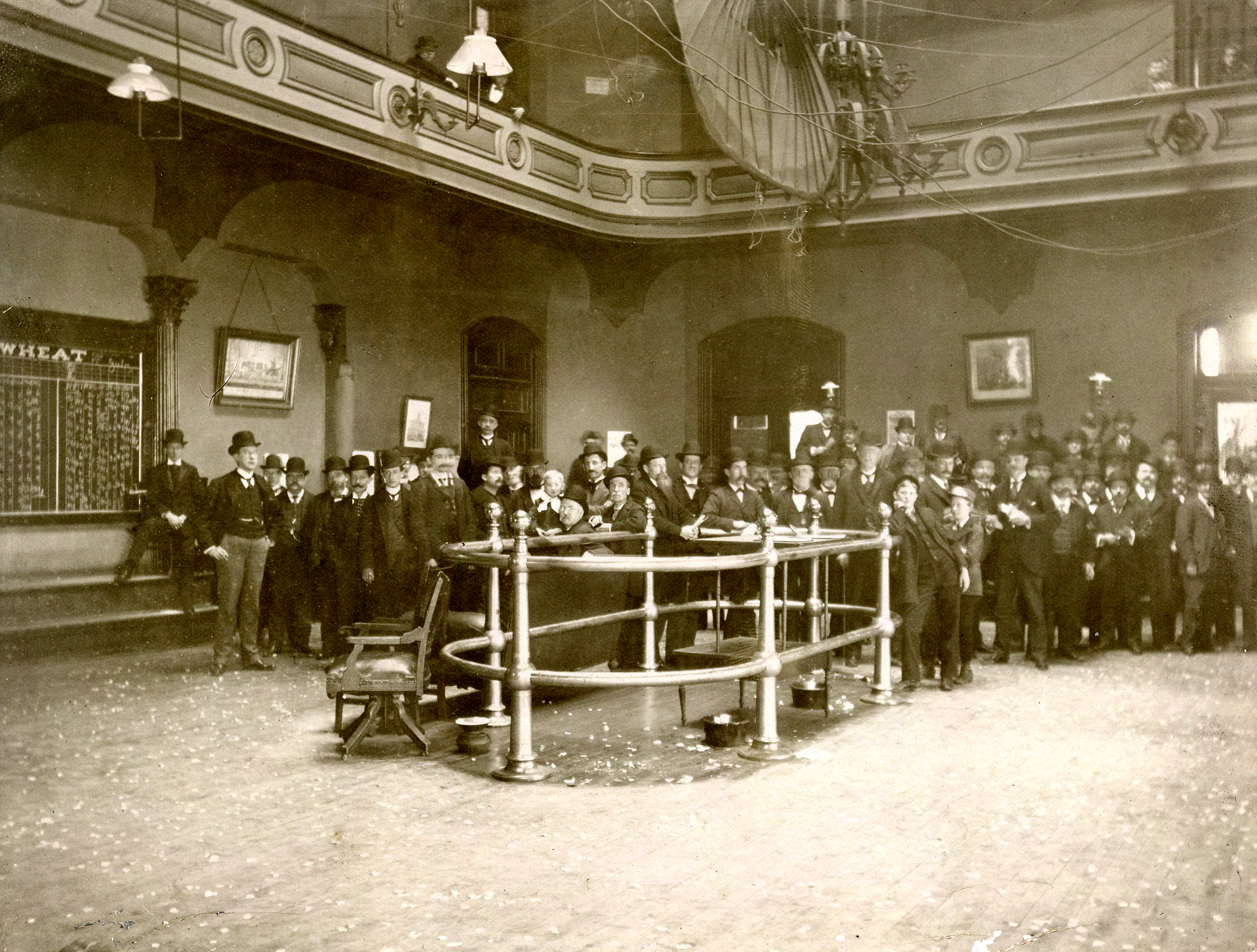

Each of the dozens of offices had a marble-topped washstand, bronze radiators, cold air ducts and transoms. There were reading parlors, conference rooms, a large telegraph office, a basement restaurant operated by Thomas Gent, a billiard hall and a barber shop in the building. Standard Oil, the nation’s largest oil concern and owned by John D. Rockefeller, had its own private offices in the Oil Exchange.

Upstairs, a water fountain called “the Aquarium,” was surrounded by a balcony featuring a nickel-plated circular railing made by Tiffany & Co. of New York City. It was called the bullpen. Skylights, two elaborate chandeliers and a bronze figure “in medieval costume holding aloft a gas lamp” completed the trading room.

Congratulations on the new exchange poured in from smaller oil exchanges in Titusville, Bradford, Warren, Petrolia and Parker as well as from dozens of oil companies. One poignant letter came from Col. Edwin Drake who was responding to an invitation to the grand opening. It read: “Due to infirmities, I have been unable to walk for more than four years, consequently am confined to my chair and to the house, only when a neighbor takes me to ride as I can’t afford to keep a horse and ride every day.”

At the opening dedication, Greenfield, president of the Oil Exchange, said, “The trade of the Oil City Oil Exchange ranks third in extent of business in the U.S., New York and San Francisco being only ahead.”

The Oil City Oil Exchange set the price of crude oil for the nation. Brokers working in the building earned a 10-cent commission per barrel from buyers and a 5-cent commission per barrel from sellers. Business was so brisk that the Oil Exchange members embarked on a second project and built an adjoining annex, similar in size to the original building, for $40,000 in 1883.

And while the Oil City Oil Exchange was “the heartbeat of the oil industry” for just over two decades and was responsible for fortunes made and lost, the extreme volatility in oil prices because of shifting transportation opportunities and wild swings in crude oil prices hit the exchange hard.

In addition, Titusville resident Joseph Seep, John D. Rockefeller’s prime oil buyer and purchasing agent, was cornering the market by 1895. In opting to pay cash directly to oil producers, Rockefeller was essentially setting the price for crude oil. There was no need for middle-men or an oil exchange.

In 1909, the Oil Exchange building was sold to the Oil City National Bank. It was razed in 1926 to make room for a new five-story bank building. The annex was demolished in 1956 to provide a parking area for the bank.

The National Transit Building

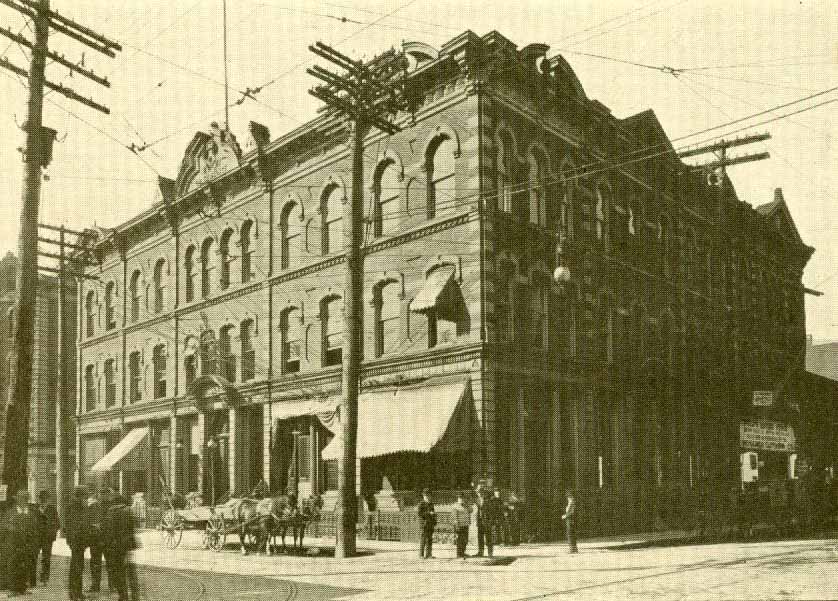

Just across the street from the Oil City Oil Exchange was the National Transit Co. building and adjacent annex. The five-story Transit building was constructed at a cost of $90,000 in 1890. The project originated with the organization of the National Transit Co. by oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller in the spring of 1881. The new company was founded to unite his trunk oil pipelines in Cleveland, New Jersey, New York City, Buffalo and Philadelphia. By 1882, National Transit came under the control of Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Trust. The company owned 13,000 miles of pipeline that could move 80,000-plus barrels of oil a day from Pennsylvania oil fields to refineries.

While National Transit had its main office at 26 Broadway (later Rockefeller Center) in New York City, the field management office was in Oil City with the general manager being Daniel O’Day. The Broadway location was described in media reports as “headquarters of one of the most powerful corporations in the U.S. in its time.” The Oil City building was the first in the world to be used exclusively to coordinate the transportation of crude oil via pipelines. Company reports indicate Rockefeller was encouraged to put the field office in New York City or Philadelphia but he deferred because of the proximity to the very busy Oil City Oil Exchange nearby and to the center of the oil producing district.

The building was completed in 1890 on land that previously was occupied by the Ohio House Hotel as well as small stores and shops. George Plummer had owned the tract but sold it in 1885 to IOOF Lodge representatives who eyed it for a new lodge. They turned around and sold it to Charles and Isabelle Lay for $10,000 in 1889 and the couple soon sold it to National Transit.

While the building was under construction, the local newspaper groused that “too many men are standing around watching and that is causing laziness among the spectators.”

The media also noted the National Transit Building “symbolizes the prosperity of the oil region and … represents the big, worldly, solid and successful oil industry.”

A June 1889 article described the new structure as “one of the more commanding edifices which grace our city – in an architectural sense the finest and by all odds the largest building devoted to the offices of a single company in Venango County or in Western Pennsylvania outside of Pittsburgh.”

The architectural firm was Curtis & Archer of Fredonia, New York. A partner, Enoch Curtis, also designed Christ Episcopal Church, Bradford City Hall and the McKinney home (now the main Pitt Campus building) in Titusville.

The National Transit building, built in the general design of the Chicago School of architecture, and its adjoining annex built in 1896, boasted some unique features. The large foundation stones came from the old Humboldt Refinery at Plumer which, when built in 1864-65, was regarded as the most expensive ever built in the oil country and one of the largest early ones. There were two elevators with one being a water-operated, wrought iron transport at the annex that was modeled after the Eiffel Tower elevator.

The hallways featured marble floors, oak woodwork and detailed frescoes. There were transoms above all the doors in the 100-plus offices to allow the free flow of air. Pneumatic tubes were installed inside the walls to allow for inter-office communications. A brick and concrete vault extended from the ground floor to the top floor with access on each floor. Many of the interior door knobs were Civil War cannonballs.

Just below the sidewalk surface was the well-known Seven Barbers Shop. One of the longest tenants in the building was Milady’s apparel shop which was in business for nearly 50 years. One area of the main building was dedicated to telegraph services and it boasted 20 to 25 telegraph operators on duty every day to track National Transit oil sales and purchases.

One window on the second floor of the main building has the initials HBR engraved on the glass. Horace B. Robinson of Oil City, the builder, etched the letters into the window with his diamond ring.

In 1911, a federal anti-trust case against Rockefeller’s Standard Oil resulted in putting National Transit out on its own. The company stock was eventually bought by Quaker State, Pennzoil, Wolf’s Head and others and offices in the two buildings were quickly filled by doctors, attorneys, real estate agencies and more.

In 1957, the National Transit Building and annex were sold to city residents Samuel Breene, C.E. Beck and Edward Stanley. Subsequent owners donated it to a local non-profit agency in 1993. Unable to fill it with tenants, the owners were forced to close both buildings in 1994. A year later, national consumer advocate Ralph Nader bought it and renamed it the Civic Renewal Center.

The property moved in and out of delinquent property tax sales until it was re-established as the Oil City Civic Center. It now houses private offices and various art studios.

Written by Judy Etzel with research by Kay Dawson and design by Natalie Cubbon.

HIDDEN HERITAGE IS SPONSORED BY:

Jack Eckert & Susan Hahn

— In Memory of Kay Ensle —

Support This Project

Donations to the library are appreciated to help offset printing costs & make this project possible! Want to become a sponsor? Email us at promotions@oilregionlibraries.org to get started!

Make a Donation