Oil Well Supply

- Judy Etzel

- January 6, 2023

- Hidden Heritage

- 12033

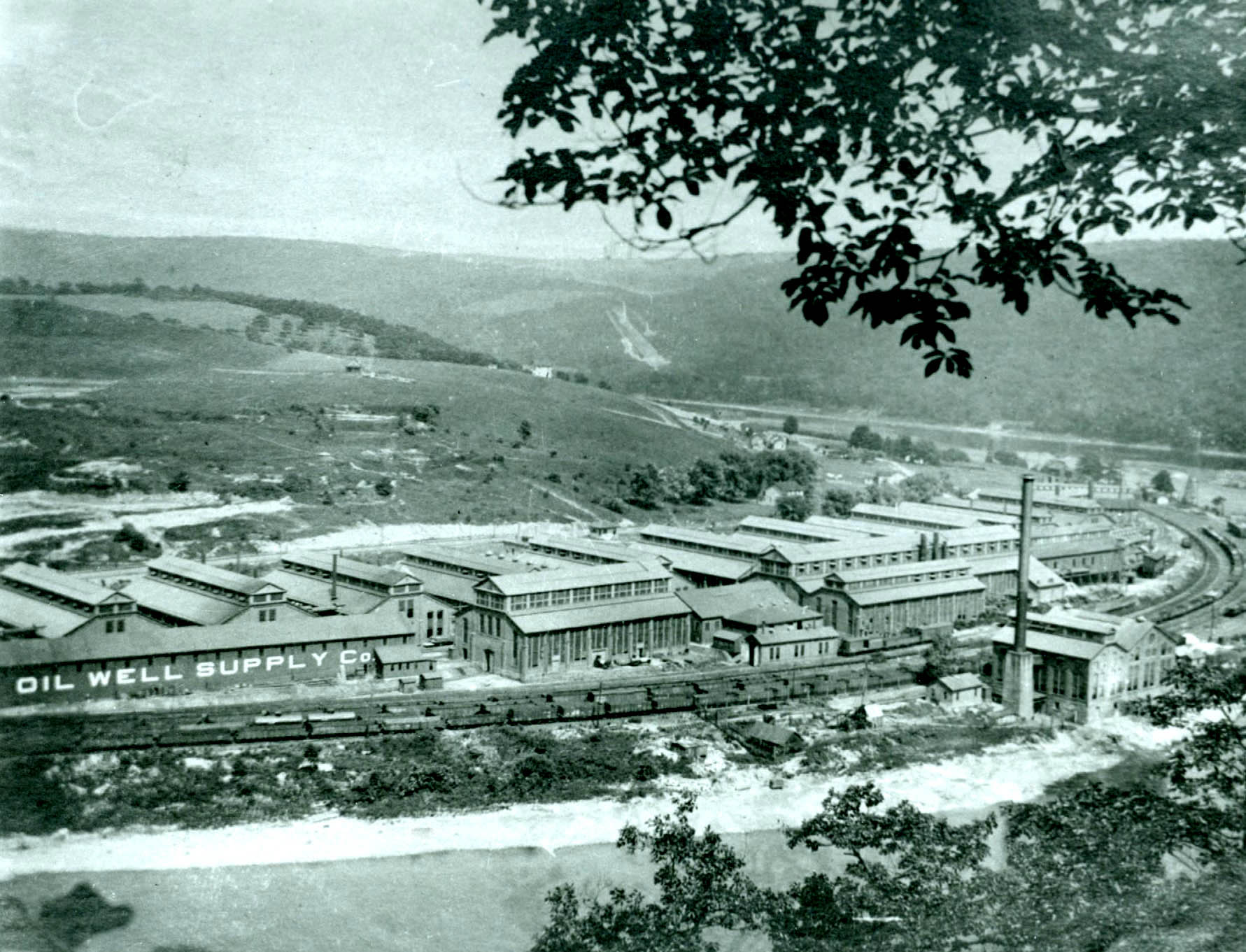

Oil Well Supply, located in a sprawling plant in Oil City’s Siverly neighborhood, was one of the city’s most unique manufacturing companies and a major economic force within the community.

No history of Siverly can be told without the story of Oil Well Supply being added to the mix. The company would take over, and later expand, the site of the former Imperial Refinery when it was shuttered and abandoned in 1894.

Oil Well Supply would provide a major claim to fame for the small neighborhood, both in a local and an international sense.

How It Started

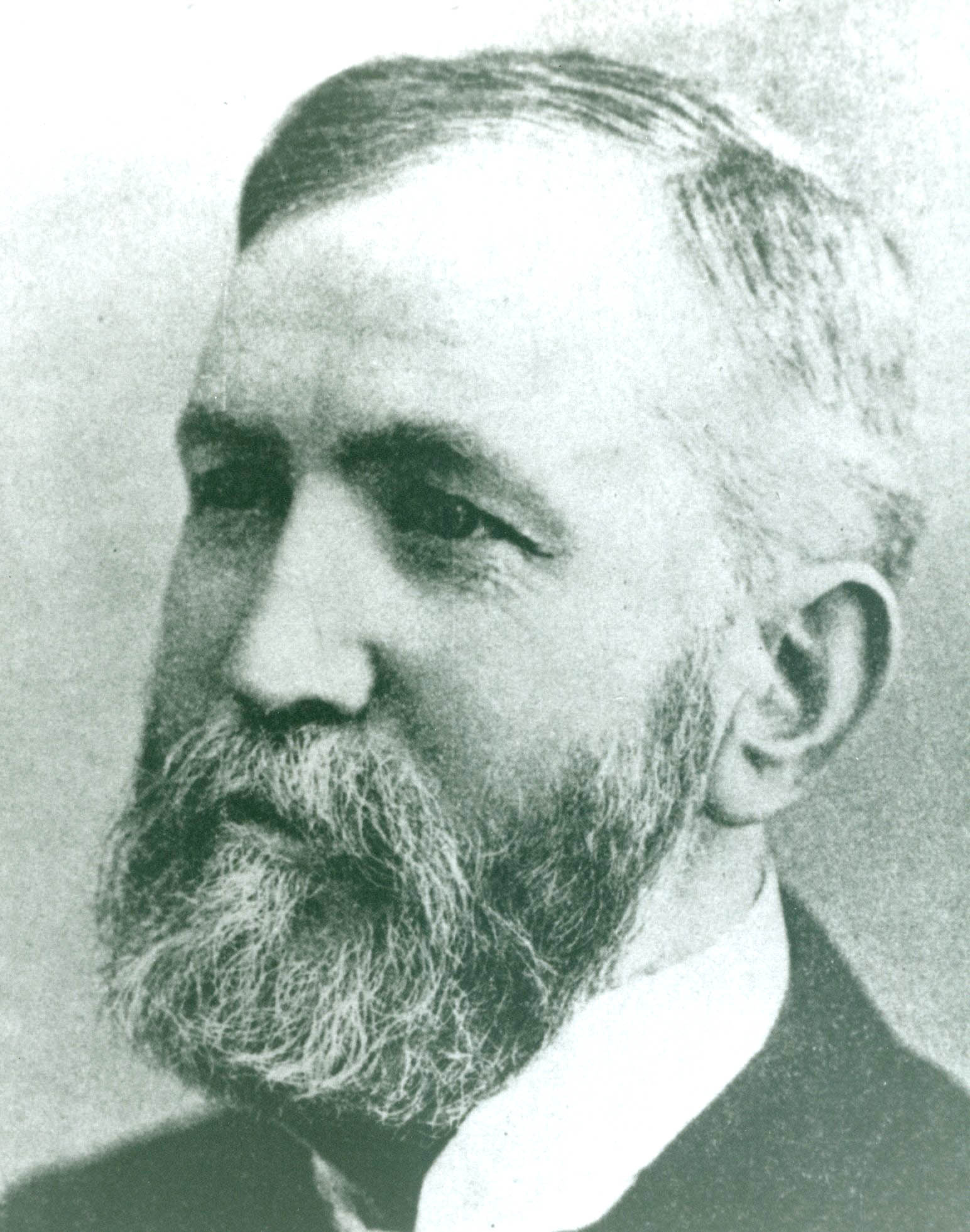

In 1862, John Eaton, a self-styled pig iron peddler who sold brass and iron steam engine parts throughout the early oil region, thought about becoming an oil prospector. However, he decided against that vocation and turned instead to become a supplier to the industry. His change of mind from prospector to supplier had profound implications for the oil and gas industry, as well as for Siverly.

That same year, Eaton opened up a small supply shop, like an oil country store, on Oil City’s Elm Street. His one-man operation was a brokerage-type of deal – he would trade one oil industry tool for another or have a blacksmith make one or fix a tool, then sell the items from his storefront. His shop was the first ever to produce equipment specifically and exclusively for the oil industry.

The inventory ranged from riveted sheet iron to drill bits and temper screws. Thanks to the flourishing oil boom, Eaton became quickly known as the “oil well supply man,” the first in the world.

As Eaton’s business grew, it attracted partners and new names – Eaton & Cole in 1869 and Eaton, Cole & Burnham in 1875. It was growing at such a fast clip that Eaton and his partners finally decided on a more descriptive name for their company – Oil Well Supply – in 1878.

By that time, the company had expanded its headquarters in Oil City, but had branches in Petrolia, Edenburg, Scrubgrass, Bradford and Karns City.

The Reputation Grows

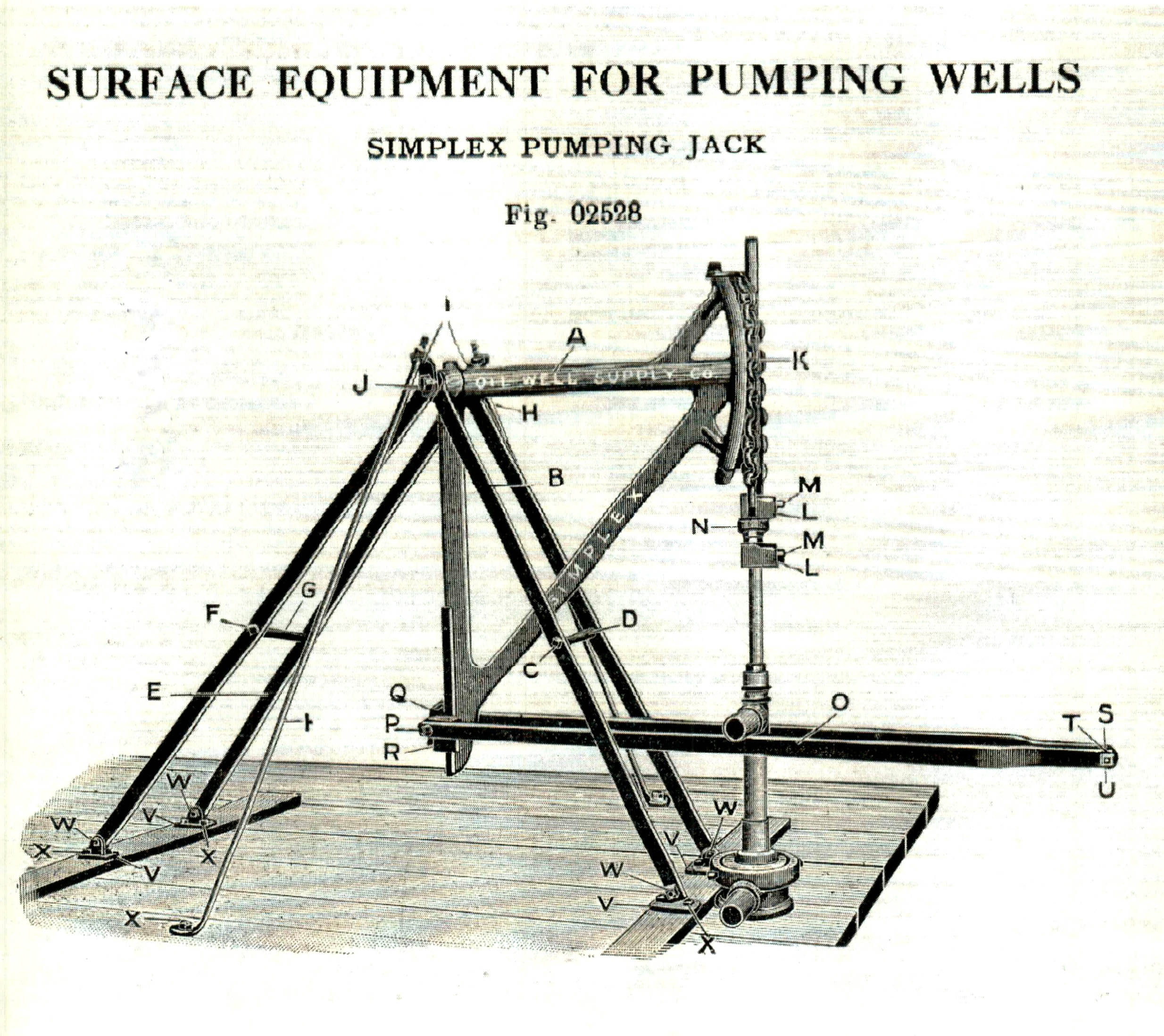

Oil Well Supply, the maker of all tools and other materials necessary to drill and pump an oil or gas well, had an international reputation by that time.

The business was so highly regarded that A.B. Nobel, a Swedish industrialist, inventor of dynamite and founder of the Nobel Prizes, came to Oil Well for machinery, men and technical advice to develop the oil fields in Russia. That arrangement marked Oil Well’s entry into the international market.

Part of Oil Well’s universal appeal was its practice of instilling uniformity in the oil industry. For example, Eaton launched specifications such as threaded tubing for pipe, a major change in the early practice of workers simply shoving pipe down a well hole like it was stove pipe.

And, Oil Well Supply adapted – the Bradford oil field came in at such a prolific rate in 1867 that Eaton invented threaded wrought iron pipe to handle the huge volume of oil. And, when the West Virginia oil fields were first tapped in 1889, Oil Well began manufacturing heavier equipment to facilitate deeper drilling in heavily coal-seamed regions.

The company’s business mantra was always – “If a tool to do a job was not available, Oil Well made one.”

In 1900, Oil Well Supply was the leader in oil field equipment worldwide. It had seven manufacturing plants – three in Pennsylvania, one each in Ohio, West Virginia, Missouri and New York – and 60-some stores in nine states and the Indian Territory out west. In effect, that made Oil Well an early operator of “chain stores.”

International business was brisk. As an example, Oil Well sent a complete drilling rig and crew to Paris for a demonstration in 1900. Orders for tools, equipment and crews were funneled into the Oil City office from throughout Europe.

Oil Well Grows

Oil Well Supply executives directed Kenton Chickering, vice president of the company, to find a larger tract to expand and consolidate the company’s Oil City operations in the mid-1890s. He was asked to scout out a 50-acre site in Siverly that had boasted the Imperial Refinery.

A key drawing point was the tract’s proximity to additional property that Oil Well already owned in Siverly. And, the land boasted natural gas wells, the fuel that would be used as the prime energy source for the plant. It was a move far ahead of its time as far as energy sources for heavy industry.

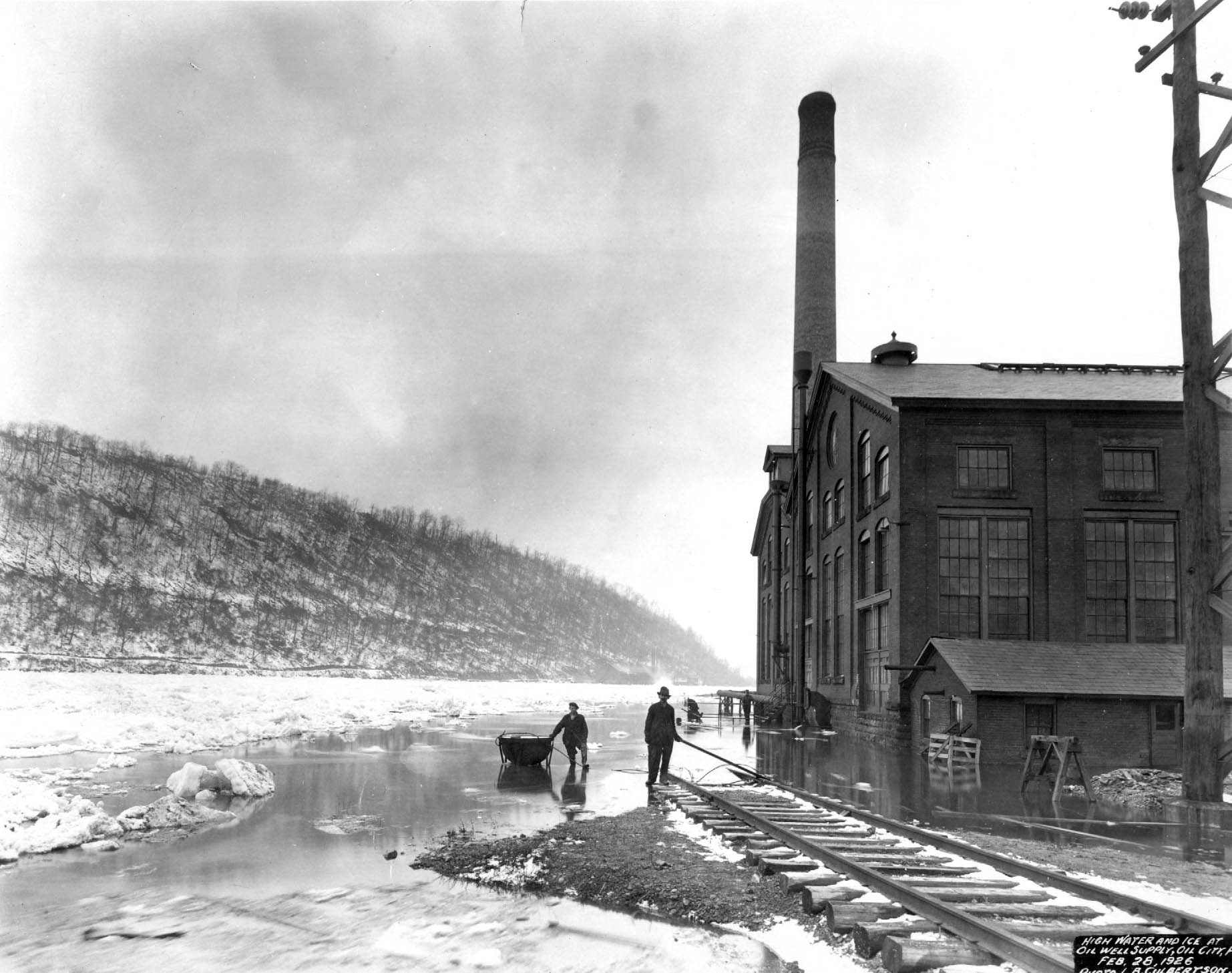

Oil Well bought the old refinery property and began constructing a huge factory along the Allegheny River. Under Chickering’s direction, the plant was completed in 1902 and named Oil Well’s Imperial Works. It immediately claimed the distinction as the largest manufacturing plant in the world for oil and gas equipment.

Neighborhood Changes

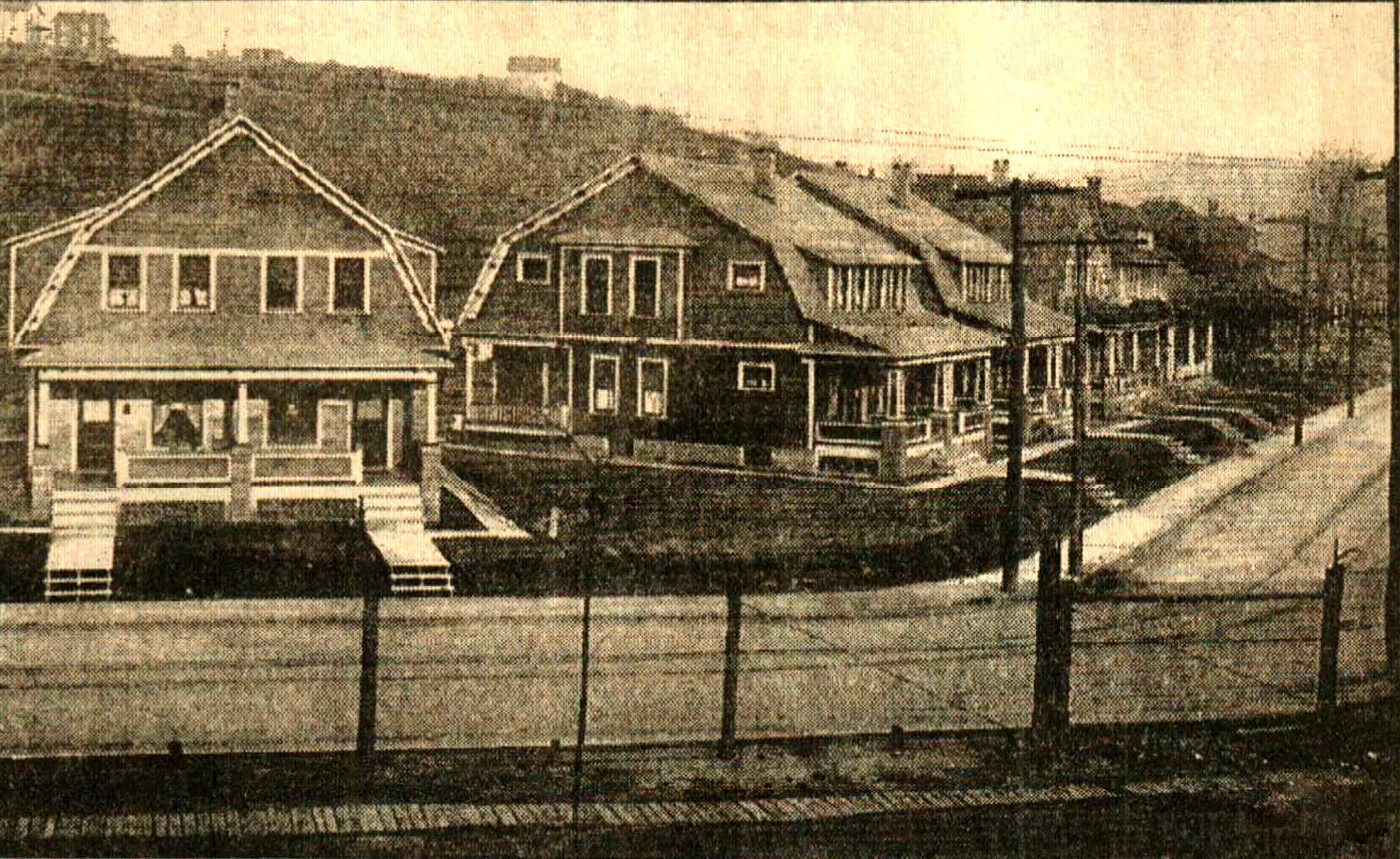

The new plant that stretched blocks along the river and included several sturdy, multi-story brick buildings, brought enormous changes to the small Siverly Borough, also known as Siverlyville.

For example, until the factory was built, Siverly residents depended on water wells and outhouses. The Oil Well project meant sewer lines and water lines were laid throughout the neighborhood. A volunteer fire department was organized and firefighting equipment was purchased. The jail and borough hall on Plum Street were refurbished.

By 1910, Siverly listed 1,616 residents. The community was booming as it claimed Oil Well Supply and the railroads as major employers. The commerce industry was well represented with dozens of grocery stores, beauty and barber shops, billiard halls, taverns, apparel shops and more doing business in Siverlyville. But it was Oil Well that offered the jobs of choice for Siverly residents. The litany of jobs included galvanizers, tinners, pipefitters, metal polishers, tool dressers, clerks, machinists, pattern makers, draftsmen, coremakers, carpenters, molders and more. Early in its history, the company would also approve a labor contract with the United Steelworkers, a move that provided employees with family-sustaining wages and benefits. Oil Well employees would comprise a large portion of the city’s middle class.

Product Line Expands

While Oil Well was inventing as it went, adapting and changing oil and gas field equipment and tools as the needs arose, the Siverly plant invented one product that would prove to be a major accomplishment. In 1908, Oil Well created a one-piece steel sucker rod to replace earlier ones that were wood poles fitted with iron couplings. The Siverly neighborhood took on an international flavor, even more than that represented by its ethnically diverse population. Oil Well was supplying equipment worldwide and so attracted representatives from numerous foreign countries that were interested in oil and gas production.

In 1905, Oil Well designed sectional oil well equipment to fit on burros’ backs in Bolivia. In 1907, Oil Well invented the first steel derricks for countries, like Egypt, where climate made wood impractical. In 1910, Oil Well opened offices in London, England, and in Tampico, Mexico. In 1925, it expanded its operations to include a store and plant in Romania. Meanwhile, Oil Well’s employee roster grew rapidly in the 1920’s and 1930’s as new production lines were added. When the gushing Spindletop wells came in Texas, Oil Well revamped one line to make rotary drilling rigs. The Seminole field in Oklahoma required more drilling speed, so Oil Well accommodated by manufacturing larger pumps that could handle a higher steam pressure. Another Oklahoma field needed higher power to drill deeper, so Oil Well bulked up the engines it made and produced a heavier version.

A Large Workforce

At each step, the bulk of those newly hired workers either came from Siverly or moved there shortly after to start work. By 1937, Oil Well had 37 buildings in Siverly where 1,300 employees worked. Its influence was substantial – in Oil City, 6 percent of the population worked at Oil Well. That meant about 20 percent of the city’s households depended on Oil Well operations. That same year, the company reported it had sent “several thousand men abroad as drillers, tool dressers, blacksmiths, machinists, rig builders, refinery operators, and pipe line men” to help establish drilling and production projects. Many of those representatives called Siverly home. In that time, Oil Well could boast of its overwhelming influence in the community – Siverly – where its largest plant was located. Its annual picnics, held at Monarch Park or Hasson Park, regularly drew more than 4,000 people. It held annual Shop Nights for fathers and sons that featured entertainment like speakers, movies, orchestras and “the Oil Well Hillbillies.”

Numerous classes, including industrial economics, petroleum engineering, and first aid, were offered at the Oil Well Plant. The company sponsored a community baseball team – the famous Oil Well Supply teams that played against the Pittsburgh Pirates and Cincinnati Reds on the company diamond at the corner of Colbert and Willow and a mushball team (it won the Northwest Pennsylvania championship in 1936) and a bowling league that listed more than 100 bowlers. Oil Well built and maintained a Siverly community playground on Wayne Street, complete with a supervisor. While Siverly was bustling in the 1930s, the real heyday would come in the following decade.

1940’s and World War II

Oil Well, and subsequently Siverly, played a pivotal role in World War II because of its manufacturing capabilities. The first big push came in December 1940 when a war-torn England ordered 50 diesel-driven pumping units, 150 miles of pipe, and accessories for water supplies. The stipulation was that it all must be manufactured and aboard a ship for transport within six weeks. Oil Well employees managed to design the special units, write the instructions for their use and manufacture the entire order on schedule. The order required transport on 38 railroad cars. Meanwhile, the company, now with an employee list of 1,600, began manufacturing hundreds of engine-driven pumping units for fuel lines and water supplies in preparation for the U.S. entering World War II. In all, the company manufactured 3,000 different items for the war effort, including oil and water drilling equipment, plus pumps, lines and compressors for both land and sea use.

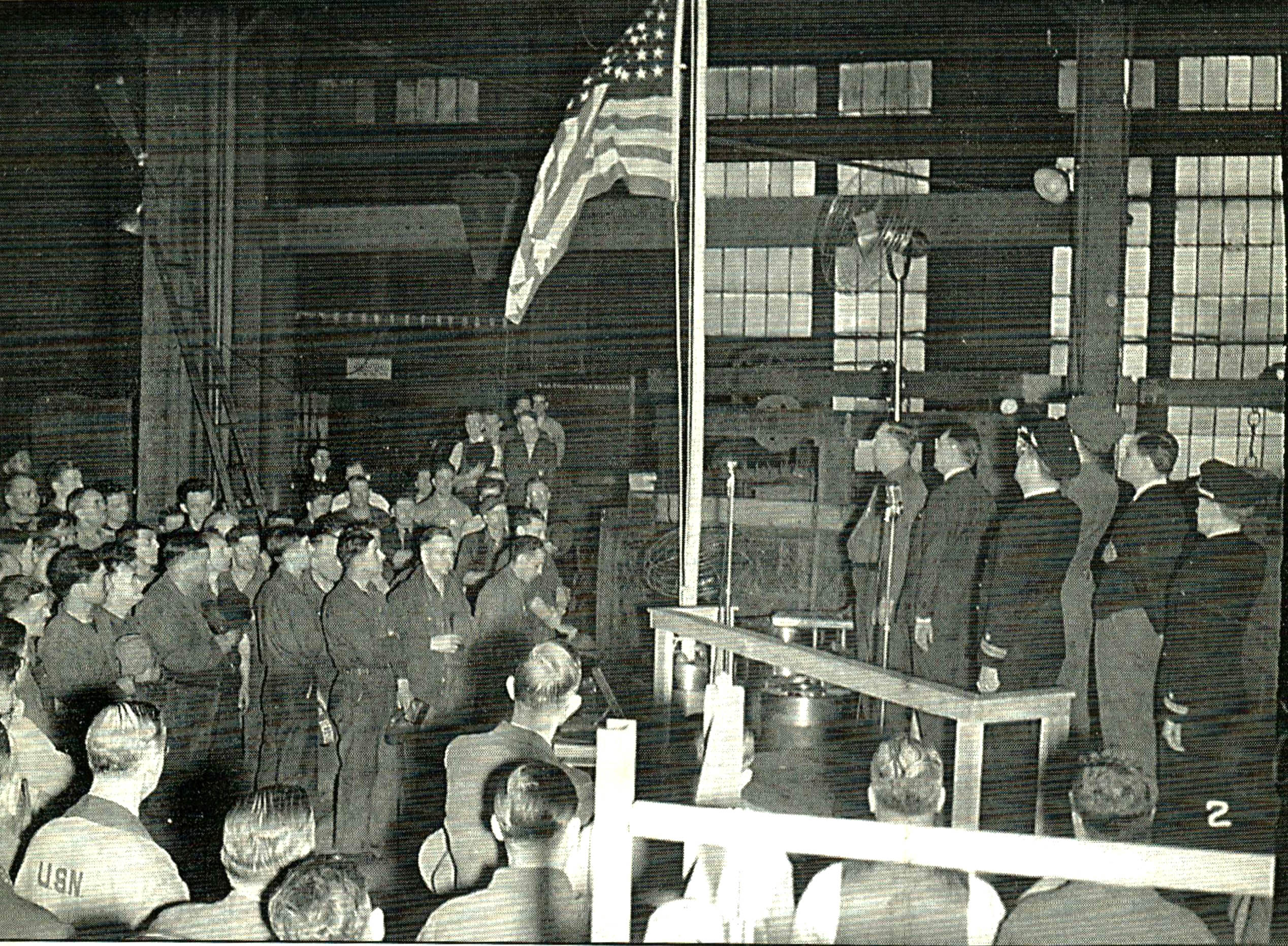

It was the armaments, though, that consumed Siverly’s Oil Well plant. The first U.S. war orders started in February 1941. The plant was the first in the nation to produce 8-inch explosive shells for the U.S. Army to use against the German defenses. It was a pilot plant for the manufacture of the breech and firing mechanism for the 155mm guns. And, the plant perfected a method of heat-treating the bars from which Tommy gun barrels were made. In addition, Oil Well handled contracts for the production of 37mm shells for the Army and 40mm anti-aircraft shells for the Navy. The Siverly plant also filled massive orders from Russia – it supplied several hundred pumps and engines to the embattled nation to help replace power at the Dneprostroi Dam wreck when the Germans invaded. Honored on a regular basis by the U.S. Secretary of War for making its production quotas, Oil Well was cited for “its long tradition of leadership” and lauded for “using its expertise and experience for Uncle Sam.” Oil Well, and thus Siverly, did more than just make equipment for the war effort – both sent their sons to war. As of Dec. 31, 1944, there were 607 Oil Well employees who had joined the armed forces to serve in World War II. As veterans returned, they were immediately put back to work at Oil Well.

Changes on the Way

In 1950, a change in the oil field manufacturing field would eventually have a dramatic influence on Oil Well and the community where it was located. U.S. Steel, which had purchased Oil Well Supply, opened a plant in Garland, Texas.

By the 1960’s, it had become the main plant for the manufacture of oil field drilling and production equipment to reflect the shift in oil production locales. Meanwhile, U.S. Steel moved to diversify its manufacturing at Siverly. The diversification included the production of continuous casting machinery, molds and gears. Employment dipped to the 900 mark at Oil Well in Siverly. In November 1981, Oil Well announced plans to expand its Siverly plant. However, the bottom fell out just one year later when U.S. Steel shifted its focus and moved some operations from Siverly to Texas. By mid-1982, Oil Well employment was down to 135. Within a year, the local plant closed.

In 1988, the City of Oil City bought the Oil Well property, by then empty and abandoned, and reconfigured it as an industrial park.

Written by Judy Etzel with research by Kay Dawson and design by Natalie Cubbon.

HIDDEN HERITAGE IS SPONSORED BY:

Jack Eckert & Susan Hahn

— In Memory of Kay Ensle —

Support This Project

Donations to the library are appreciated to help offset printing costs & make this project possible! Want to become a sponsor? Email us at promotions@oilregionlibraries.org to get started!

Make a Donation