Join the Club

- Judy Etzel

- April 15, 2022

- Hidden Heritage

- 3328

Oil City enjoyed a vibrant social atmosphere during its early heyday that yielded dozens of clubs, scores of community projects and plentiful services to its residents.

While many of the organizations were fraternal, military or religious in nature, others focused entirely on having a good time.

Two of the more outstanding clubs of that nature boasted their own buildings and listed membership rosters of hundreds of local and prosperous men.

They were the Ivy Club on Seneca Street and the Venango Club on West First Street.

The Venango Club

Edward Hopkins, general manager of the United Pipe Lines in Oil City, began the construction of a huge and elaborate family home at the corner of West First Street and Division Street on the city’s South Side in 1879. Near its completion, Hopkins became ill and unexpectedly died at the age of 34 in January 1880.

When the home was finished, his widow and their two young daughters moved into the house. The three-story residence boasted nine fireplaces, each with its own customized Minton Stoke-on-Trent decorative tiles. It had 14-foot high ceilings and an open stairway in the center of the building. A skylight some 50 feet above the first floor provided illumination for the fancy staircase.

In 1886, the Hopkins family moved out and the house was sold to Charles F. Hartwell, employed as general manager of the Brady’s Bend Mining Company. He, too, found the large residence challenging and the property eventually wound up at a sheriff’s sale in 1902.

John B. Smithman, an oilman and owner of the city’s public transit system, bought it at the behest of several Oil City men who wanted to form a social club.

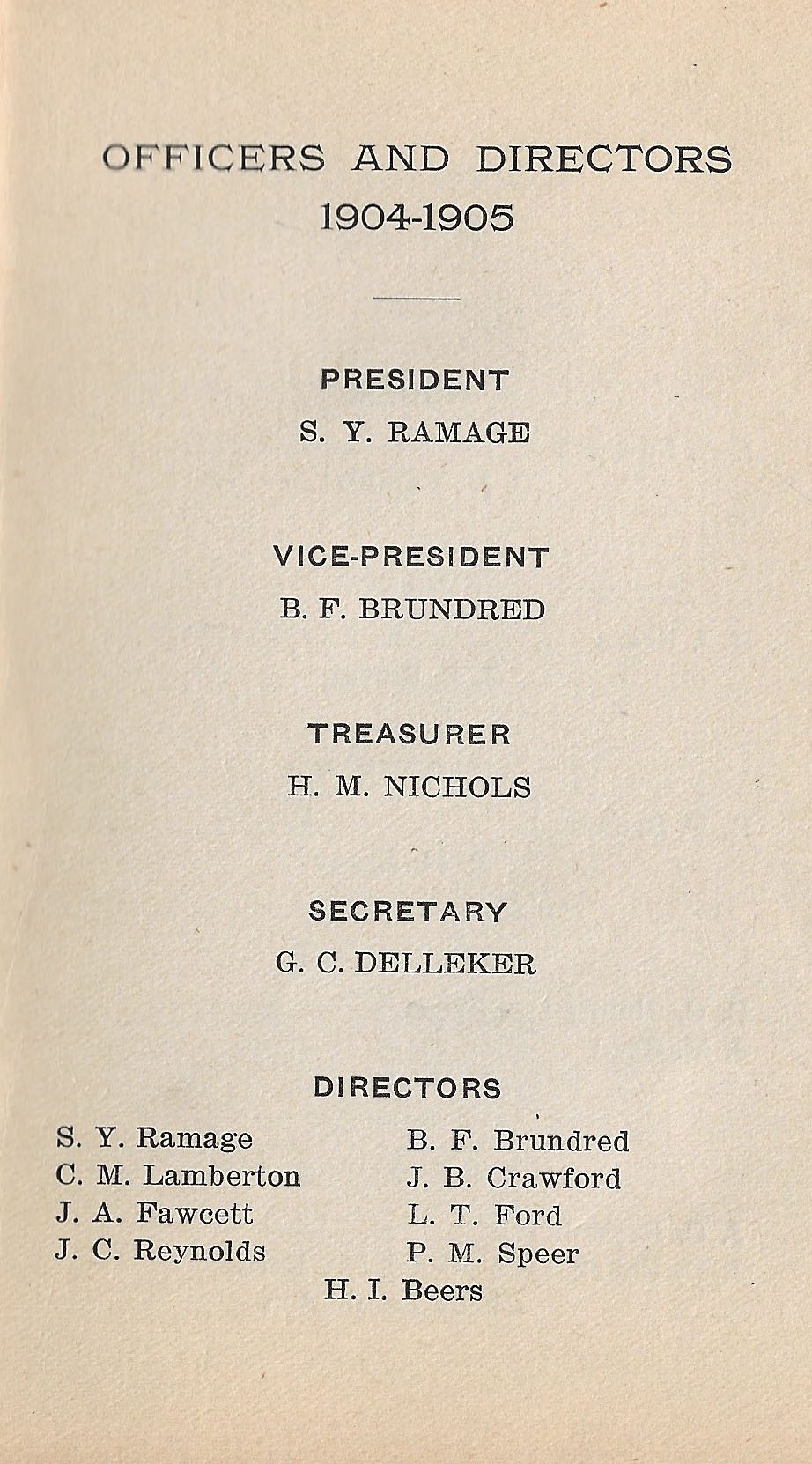

The Venango Club was incorporated on Sept. 14, 1903, and took title to the former Hopkins home. The initial board of directors included S.Y. Ramage, president, and C.M. Lamberton, J.A. Fawcett, J.C. Reynolds, B.F. Brundred, J.B. Crawford, L.T. Ford, P.M. Speer and H.L. Beers. Financing consisted of the selling of stock in the new club.

Eligible for membership were men “of good character, at least 25 years of age and owner of two or more capital stock of the club.” A potential member must live in the city or within five miles of the city. Endorsements must come from three members in order to be considered. Dues were $3 a month.

One of the club rules noted that if a member was thrown out, “the fact and reasons therefore shall be posted upon the bulletin of the club for 30 days.” Guests of members were strongly warned “not make themselves obnoxious to club members.” And, there was to be no gambling at any time and no table games or billiards from midnight Saturday to Monday morning.

City resident William Bowen was quoted in a newspaper article that “the club felt little impact during Prohibition … (and there) were wonderful stories of narrow-escape raids as liquor supplies were whisked out the back door and stashed in the homes of nearby members.”

During World War I, the Venango Club served hundreds of free roast chicken lunches to local soldiers preparing to deploy for service overseas.

The Venango Club was considered a center of social life in Oil City until hard times leading up to the Depression, plus competition from other clubs in the area, forced it to close in 1927. Two years later, the club building and its contents were sold at auction.

The house was leased to Florence McFadden who opened a dance studio in part of the building. She also lived there. However, news accounts show that enterprise ended abruptly in 1936 when McFadden married a student of hers who was still in high school.

While some tenants continued to live in the house, divided into apartments, the building rapidly deteriorated. Police were often called to the property to catch vandals as well as escort young boys off the site when they were spied crawling out of the third-floor windows and running around a ledge just below the roof line.

The building was sold in 1952 to the Tree of Life Synagogue members who would demolish the house and construct a new worship center on the property.

The Ivy Club

In the same 1879 year that the Hopkins family was building its new mansion on the South Side, a group of local businessmen across the river were forming a new social club. On May 15 of that year, 57 members of what would be called the Ivy Club received their charter. Charles Lay was elected president.

The name, according to reports, was suggested by member George H. Cronyn who claimed the Ivy Club title would reflect “the clinging together of its members.”

The first Ivy Club quarters were located on the third floor of the Reynolds, Lamberton and Company building on Seneca Street. It had been a gymnasium club that had gone out of business. Club members ponied up money to buy the gym equipment and lease the space for an organization that would be “a gentlemen’s association with a social life of high ideals.”

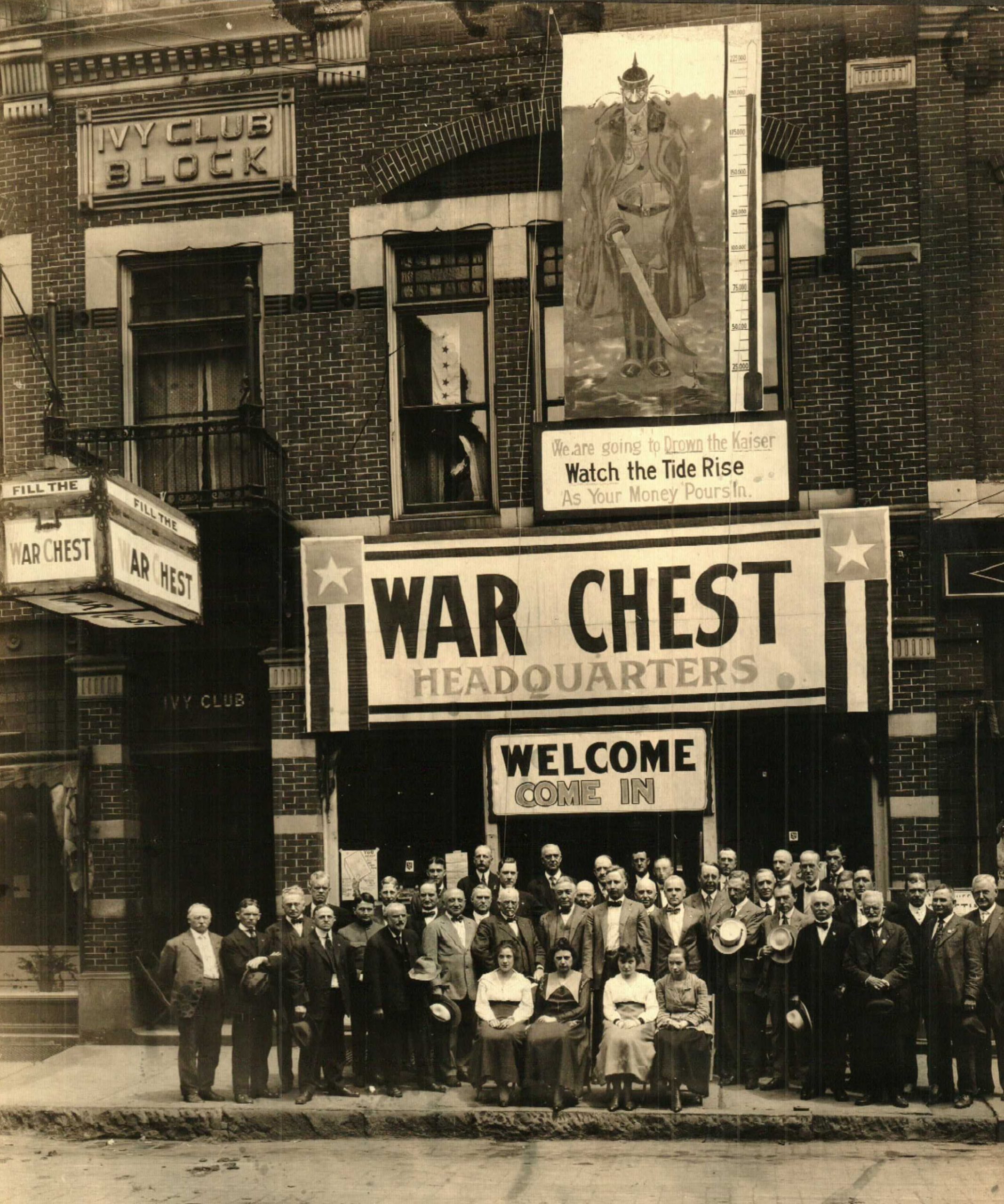

In 1887, a move was made to a new building, one that featured a granite stone chiseled with Ivy Club high atop the multi-story structure, constructed by Robert Lamberton and C.H. Duncan at 27 Seneca St.

Included in the new setting were a library, piano, card and billiard tables and a well-equipped gymnasium. The rooms, noted the newspaper, were “beautifully appointed.” The bylaws were short and to the point: “Liquors, gambling or anything unworthy of a place in homes of refinement are excluded.”

Described in promotional materials as a “fashionable gentlemen’s recreation center,” the Ivy Club became well known for its lavish parties. It was the location for many debutante balls and young ladies’ coming out parties. “The cream of Oil City society belonged to the club” claimed its membership brochures. Dances at the club were considered social events of the city.

In its early days, the Ivy Club listed a roster of about 400 male members. However, the advent of other top-drawer social venues in the early 1900s put a dent in the Ivy Club’s stature. Competing for the same members were the Oil City Boat Club, the Venango Club and the new Wanango Country Club.

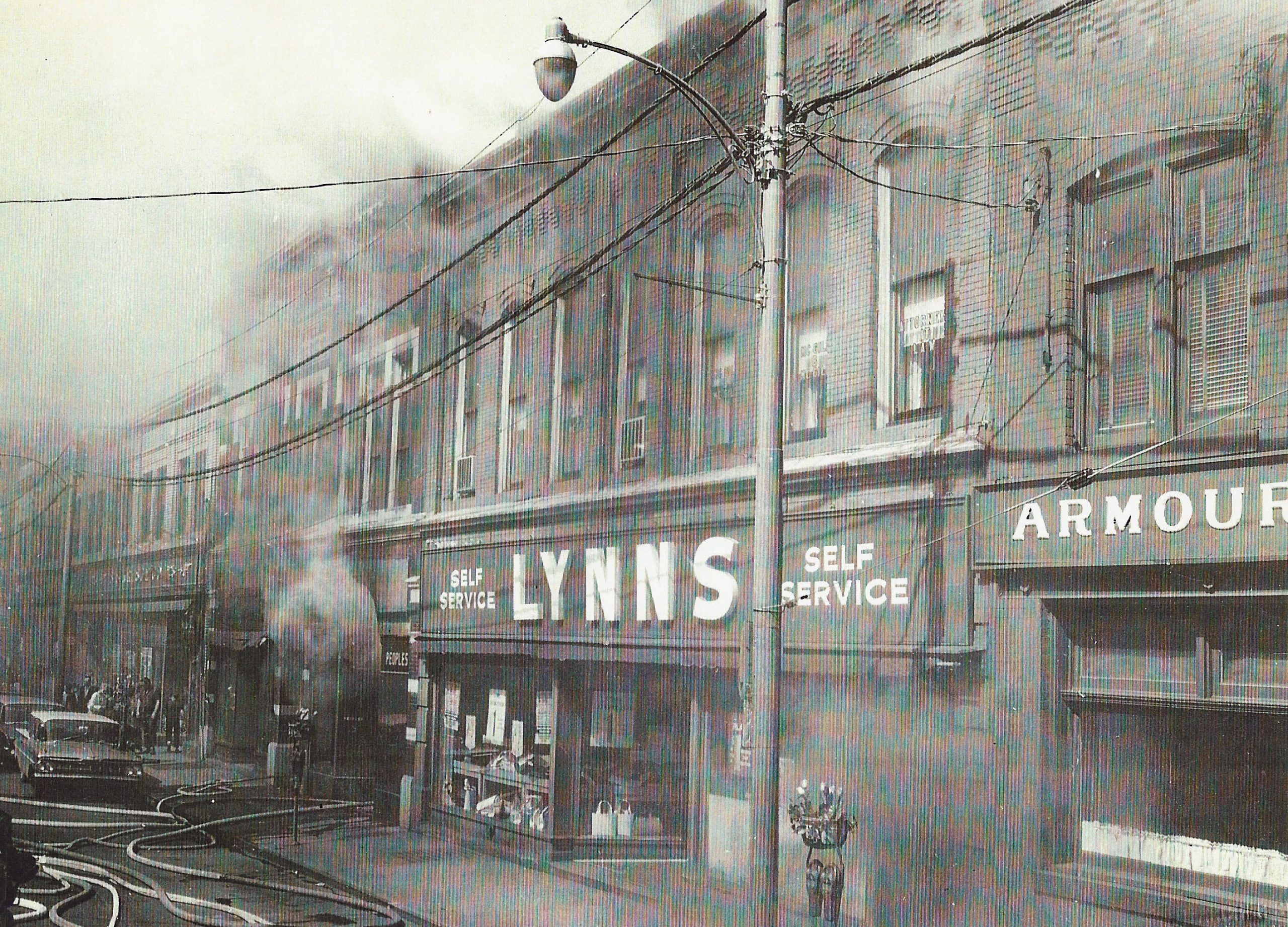

In 1920, the Ivy Club disbanded and the space it leased in the building that bore its name was later rented to a variety of businesses that ranged from apparel stores to a meat market and teens’ club.

On May 2, 1964, the downtown landmark, then vacant and due for demolition in the city’s redevelopment plans, caught fire. The blaze was suspected to have started with an overheated electric hot plate on the first floor.

A City Loaded With Clubs

As the Venango Club and Ivy Clubs were eyed as the social centers for what their members insisted was “the cream of the crop” in Oil City, more than 100 other clubs were functioning within the city limits.

Early Oil City directories listed the social organizations in several categories, including Secret Societies, Semi-Military, Social and Trade groups. In 1925, there were 102 organizations that fell under one of those categories.

The trade organizations reflected the wide diversity of occupations thriving within the city. There were labor groups for dozens of professions, including musicians, tailors, moving picture operators, railway signalmen, paperhangers, street/railway workers, switchmen engineers, barbers, bricklayers, masons, blacksmiths, locomotive engineers, iron moulders, hod carriers and many others. The entries also included the Oil City Lawyers Club and the Oil City Medical Club.

The Secret Societies included the Knights of Columbus, IOOF and the Masonic organizations and their numerous affiliates. Among those entities were Patriarch Militants, Philae Sanctorium, Maccabees, Ancient Order of Hibernians, Knights of Pythias, Protected Home Circle and others.

The Moose, Eagles and Elks clubs were flourishing as were political clubs that over the years would range from the Roosevelt Young Democrats to the John Birch Society. There were recreational groups such as the Riverside Canoe Club, YWCA and YMCA, Oil City Trapshooting Club, Oil City Tennis Club and Oil City Motor Club.

Some organizations’ purposes have been lost to history. Oil City club entries in the mid-1920s include the Eureka Club, Daughters of Isabella, Athene Club, the Hub Club, Home Watchmen of America, LOOM Lodge, MWA Camp, Twentieth Century Club, Quoto Club and more.

A few city clubs focused on ethnic heritage, such as the Polish National Alliance and the Pulaski Club and the Ukrainian National Aid Association headquartered on Standard Street. Some were specific in their goals, most particularly the numerous Women’s Christian Temperance Union branches in most of the city’s neighborhoods.

Service organizations also included the Oil City Business and Professional Women’s Club, Rotary, Kiwanis, Lions, South Side Businessman’s Association, Oil City Garden Club and others.

One club, though, gained a measure of fame for its creed. In a special women’s edition published by The Derrick in February 1896, the Oil City Thimble Club offered this: “The club is justly proud of one thing, and that is that no scandal is ever talked at the meeting.” The mission was simply “to sew.”

DID YOU KNOW?

The first complete wireless outfit in Oil City was successfully installed by the National Transit Telegraph Company in late February, 1914. A preliminary test showed that telegraph operators were able to read “with distinctness”, noted a public report, messages from Key West, FL, Long Island, NY, and Roanoke, VA.

The poles, each 40-feet high and 158 feet apart, were erected on the top of the National Transit Building at Center and Seneca streets.

Written by Judy Etzel with research by Kay Dawson and design by Natalie Cubbon.

HIDDEN HERITAGE IS SPONSORED BY:

Oil Region Alliance

Gates & Burns Realty

Support This Project

Donations to the library are appreciated to help offset printing costs & make this project possible! Want to become a sponsor? Email us at promotions@oilregionlibraries.org to get started!

Make a Donation