Monarch Park

- Judy Etzel

- April 1, 2022

- Hidden Heritage

- 7088

One of the area’s most intriguing places was Monarch Park, a sprawling tract located midway between Oil City and Franklin. Extremely popular, the venue drew thousands of summertime visitors who could dine, dance, play and more.

The history, though, was fleeting and the park would close less than three decades after its founding.

Central to both Monarch Park’s debut and closure was the streetcar.

How It Started

In 1886, Oil City resident John B. Smithman received a charter from the state of Pennsylvania to form the Oil City Railway Co. Three years later, the City of Oil City granted him the right to build and operate an electric street railway within the city.

On Thanksgiving Day, 1893, Smithman launched his trolley service in Oil City.

While the public transportation service was thriving, Smithman had an idea on how to increase revenue for the Oil City Railway Co. He bought 500-plus acres of forest land in Cranberry Township. The site was at the midpoint between Oil City and Franklin.

Smithman then extended the rail lines – one from Oil City in 1896 and another to Franklin in 1900 – to his newly acquired property. He called it Smithman Park and began to convert the acreage into a public park.

However, Smithman decided to get out of the trolley business and sold his company as well as 60 acres in the Cranberry Township tract to Daniel Geary’s rival Citizens Traction Co. of Oil City.

The business deal changed the park’s future as well as its name.

The Park Blossoms

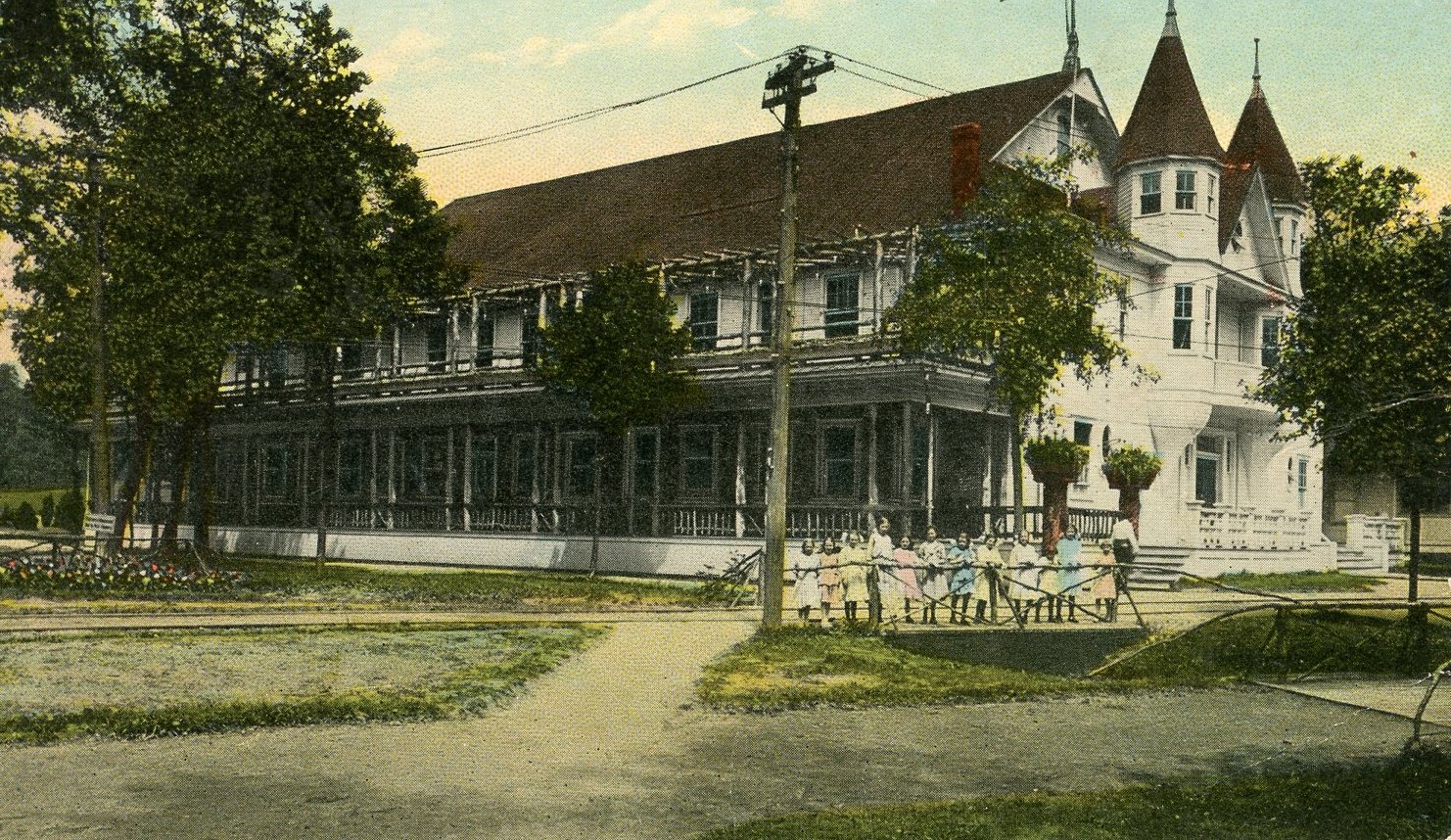

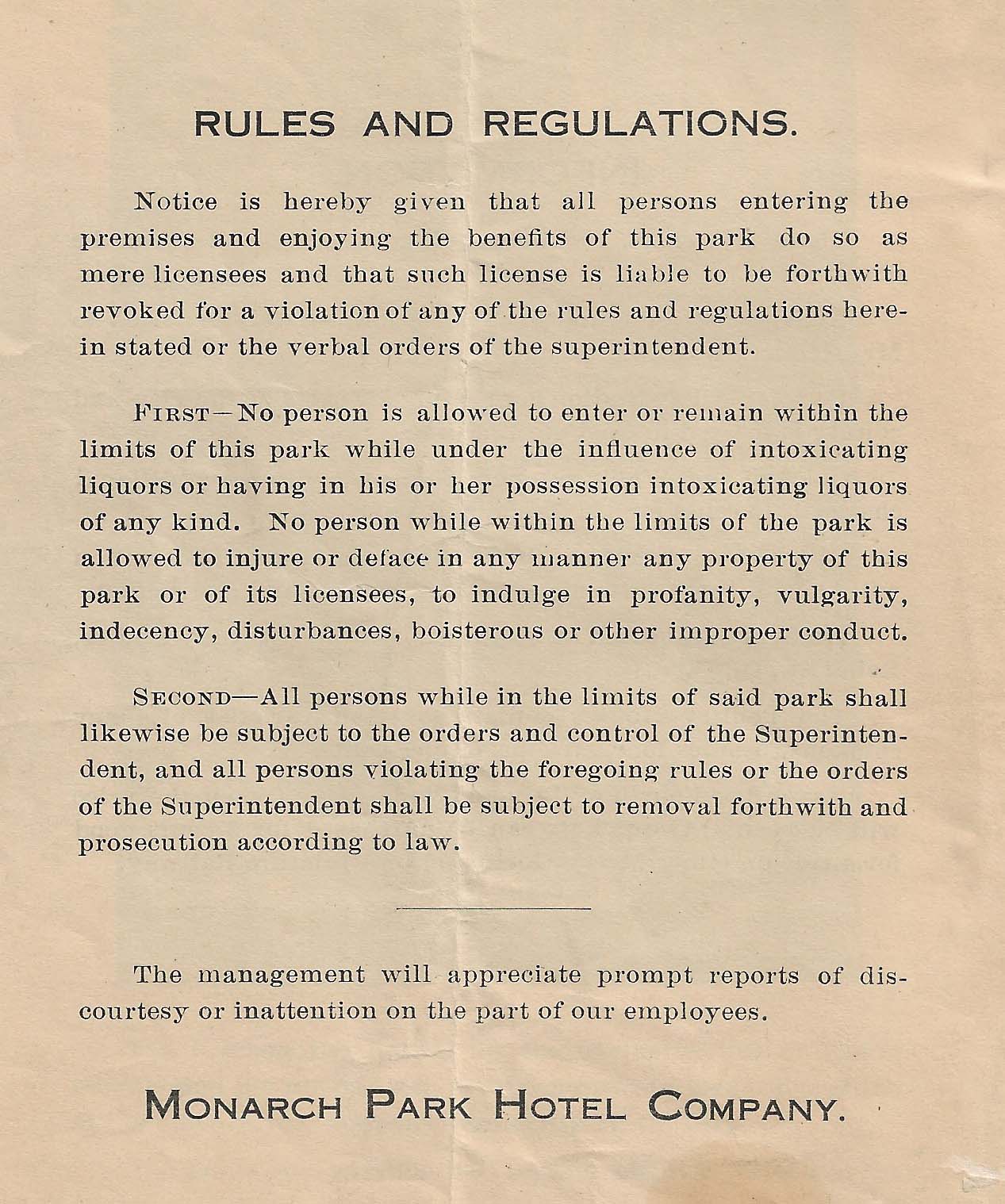

Daniel Geary, the new owner, promptly changed the name of Smithman Park to Monarch Park to celebrate his wife whose maiden name was Monarch. He operated the park under the name of the Monarch Park Hotel Co.

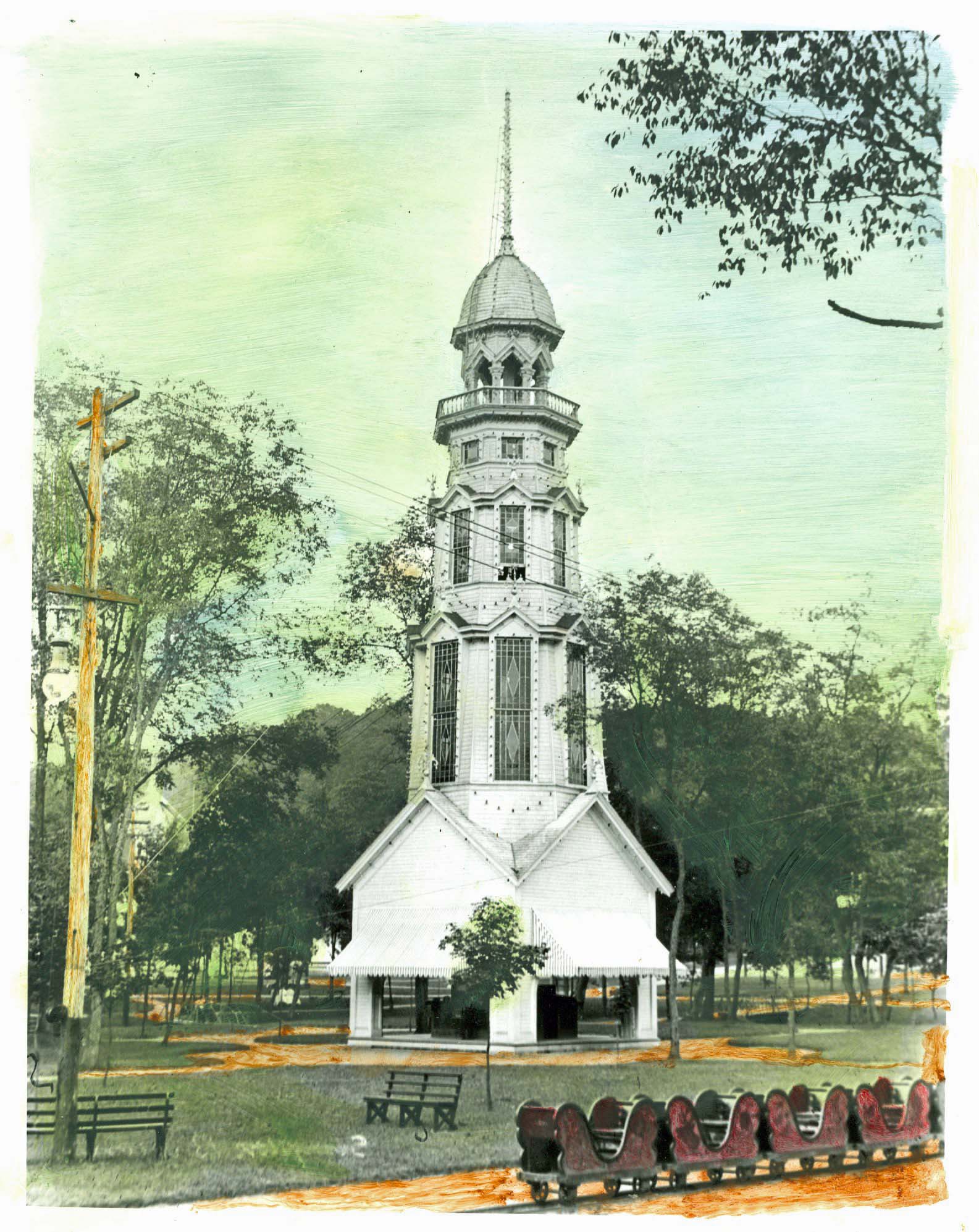

The Citizens Traction Co. featured 70 trolley cars, each of which would seat 90 patrons on benches. The streetcars bound for Monarch Park from both Franklin and Oil City had open-air sides for the summer transits. Each streetcar weighed 23 tons and traveled at a speed of 50 miles per hour when in the countryside.

Even more park-bound visitors traveled by hanging on to the running boards along the street cars. The cars made trips to and from Monarch Park at 20 minute intervals.

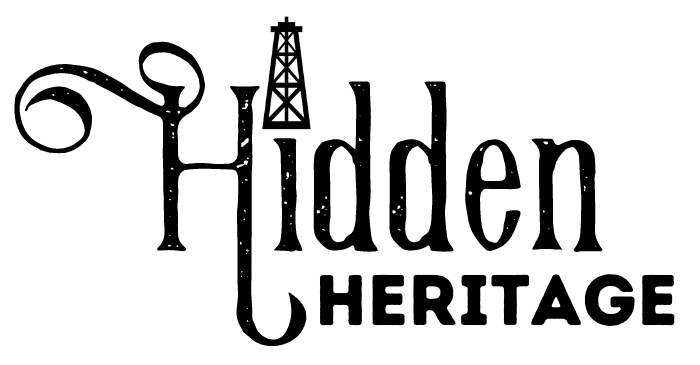

Geary hired Guy J. Hecker, a former baseball star with the Louisville Sluggers, to work summers at the park. The park superintendent was Bernard “Barney” McCue who took great pride in the elaborate flower gardens and gravel walkways, plus a few wood boardwalks, within the park. McCue and his wife lived in an apartment above the picnic pavilion.

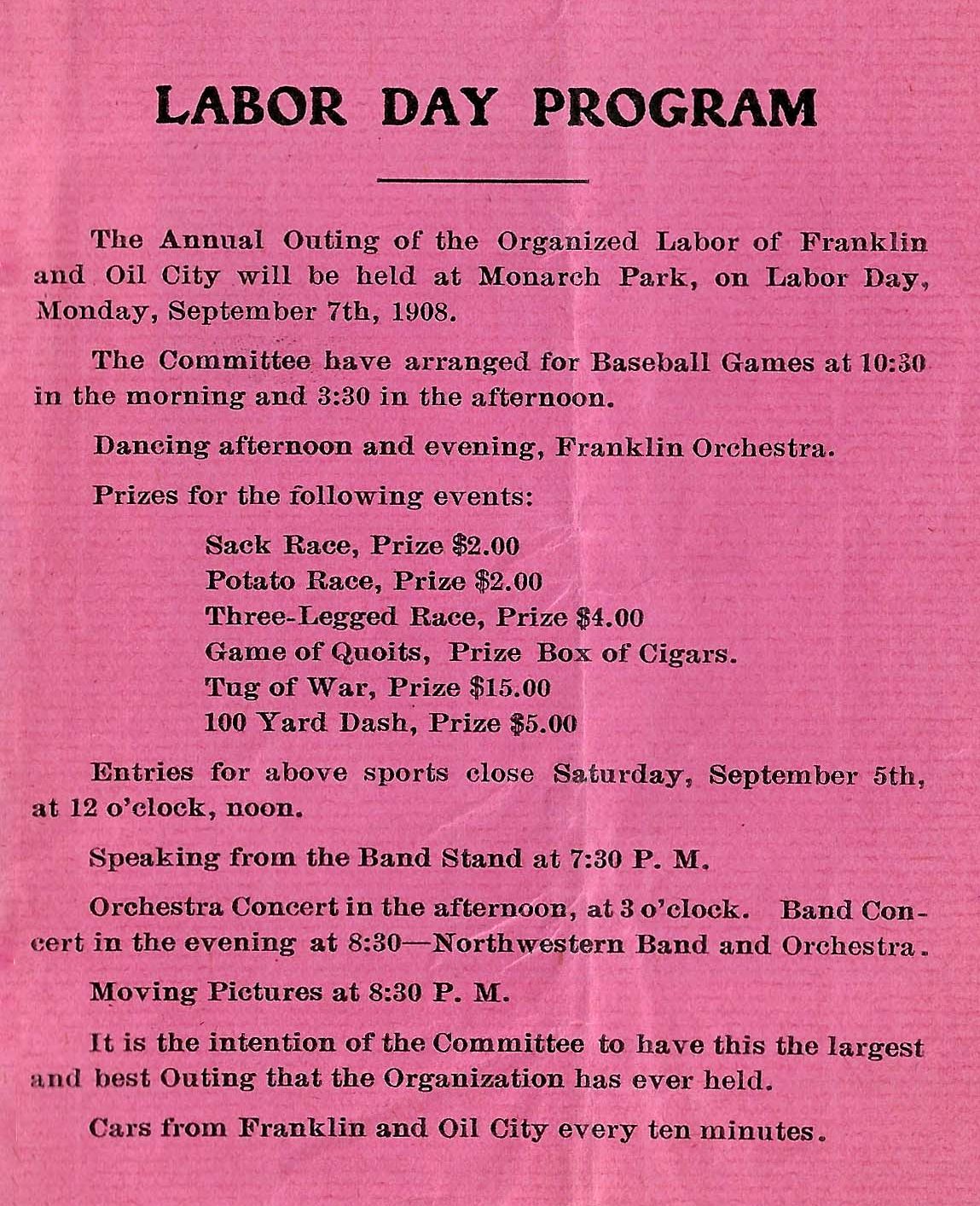

In the peak summer weekends, up to 15,000 visitors traveled to Monarch Park. The Memorial Day, July 4 and Labor Day attendance would hit records at 20,000 to 30,000 patrons.

The crowds were even larger during times when the park was rented out to groups for veteran and class reunions. Companies, too, often held their annual picnics at the park.

One large gathering was held Aug. 1, 1917, when more than 5,000 people attended a day-long picnic to honor Co. D, 16th Pennsylvania Regiment. It was comprised of National Guard members from Oil City and Franklin who were preparing to ship out to Camp Hancock, Ga., for military training before being deployed to the World War I battlefields in France. The picnic was arranged by the South Side merchants who contracted for special trolley runs to shuttle the soldiers and their families back and forth to the park. Crowds were also large for special events such as the annual Baby Contest at which mothers and their toddlers flocked to the park. There were also athletic contests for those wishing to win at track and field events and baseball.

Each weekend featured a full orchestra, including many top tier national groups, playing for concerts and dances. Area bands performed during the weekdays.

Unfortunately, the growing popularity of automobiles plus a public preference to travel to other resorts, including the sea shore, cut dramatically into park attendance by the mid-1920s. The trolley company tried to revive the operations by adding a swimming pool but it was filled with water from several natural springs in the park and proved too cold for bathers.

Adding to the drop in attendance was the loss of the Big Rock Bridge. The span across the Allegheny featured a second level designed exclusively for trolley traffic. In 1926, an ice gorge heavily damaged the bridge which had been a main route for Franklin residents traveling to Monarch Park. Meanwhile, what is now Deep Hollow Road was at that time a narrow and twisting roadway that was not conducive to heavy traffic.

The last Citizens Traction streetcar to Monarch Park was on May 31, 1928. The park was briefly leased to a private developer but operations were soon shut down and the property put up for sale.

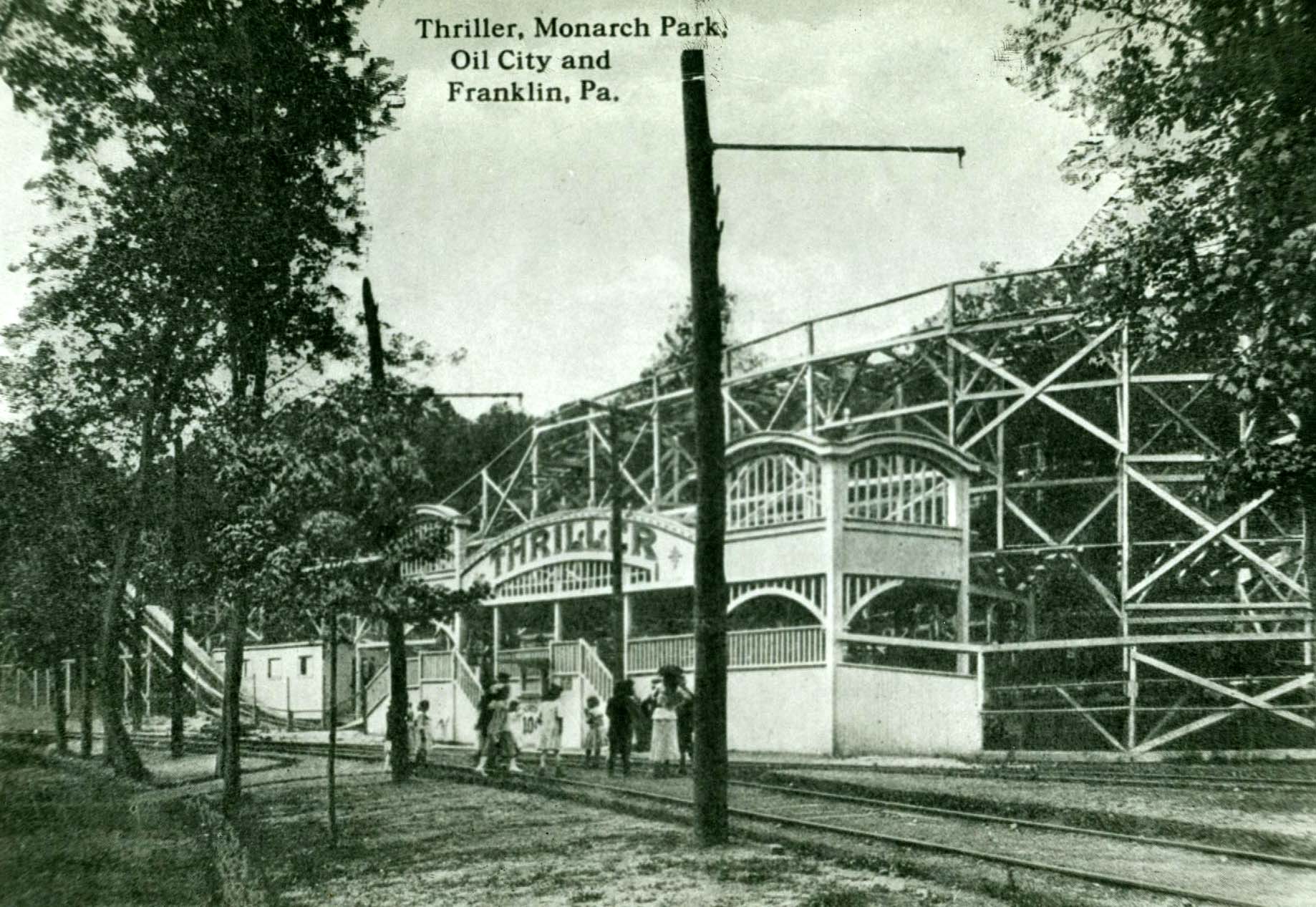

All of the buildings were dismantled and sold for scrap. The Brundred Oil Co. of Oil City bought the wooden portion of the roller-coaster Thriller, the merry-go-round shelter and the streetcar depot. The wood was used to build a warehouse on Cornplanter Run and a number of power houses on oil leases.

The maple flooring in the huge dance hall as well as other wood throughout the building were bought by Harry Manheim of Oil City who used the materials to build three houses near the corner of Grove and Harriott Avenues.

In 1939, the Waltonian Park Association bought the park, by then devoid of buildings, and continues to use the property.

Park Amenities

Monarch Park, a sprawling tract along Deep Hollow Road between Oil City and Franklin, flourished from the late 1890s until it shut down in the late 1920s.

In that brief span, the trolley company-owned park boasted amenities that made it one of the most spectacular small parks in a tri-state area. Patronage in the summer months soared into the thousands as local residents as well as out-of-towners took advantage of all the park had to offer.

Here’s a listing of those attractions:

- There was direct transportation via open-air trolleys from Franklin and Oil City on a summer schedule that saw departures and arrivals every 20 minutes.

- Numerous outdoor recreational games were available to the public. Horseshoes, quoits, a baseball diamond, a running track, swimming pool and more were available for play in the park.

- A poultry house was open to visitors. The park poultry listing included 14 varieties of “fancy chickens”, according to advertisements, and four varieties of pheasants.

- A splendid carousel featuring several ornate replicas of horses was a popular attraction. The horses were manufactured by the Denzel Co. of Philadelphia.

- There were four bowling alleys in the park. Bill Jackson ran the operation and later, when the park closed, opened up Jackson’s Bowling on Oil City’s South Side.

- The park featured half a dozen springs and at least one small waterfall. The artisan springs provided drinking water with one small building providing heated water for picnickers. One anecdote from a resident who recalled the park noted that everyone needing a sip of cool water used the same tin cup chained to the water fountain.

- There were reports that the park had areas where there was quicksand. One story insisted that the sands had at one time swallowed a cow.

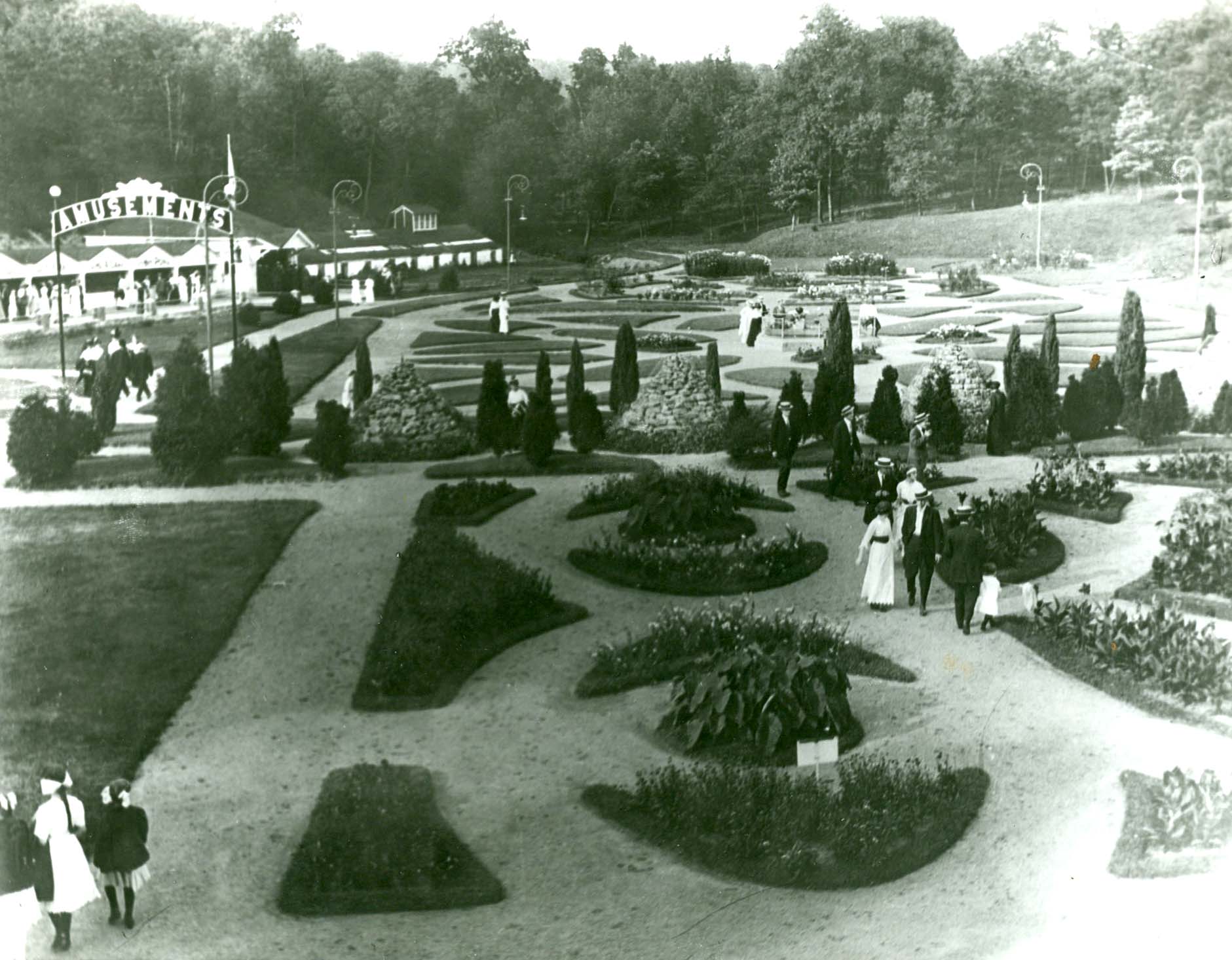

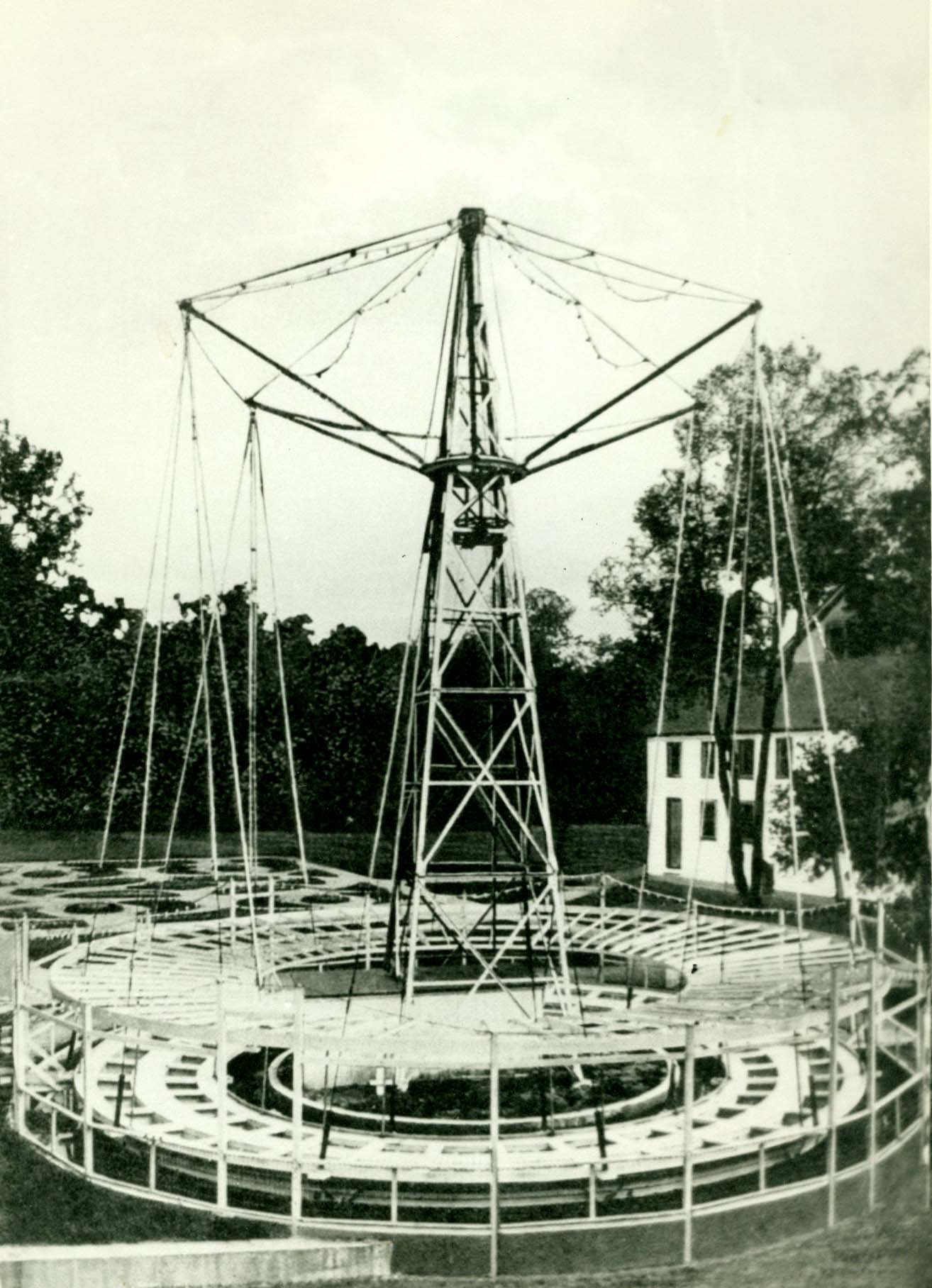

- One attraction dwarfed everything else in Monarch Park. It was the White Way Electric Tower that soared 120 feet high. It featured 4,000 16-candlepower colored light bulbs. There was a refreshment stand on the ground floor.

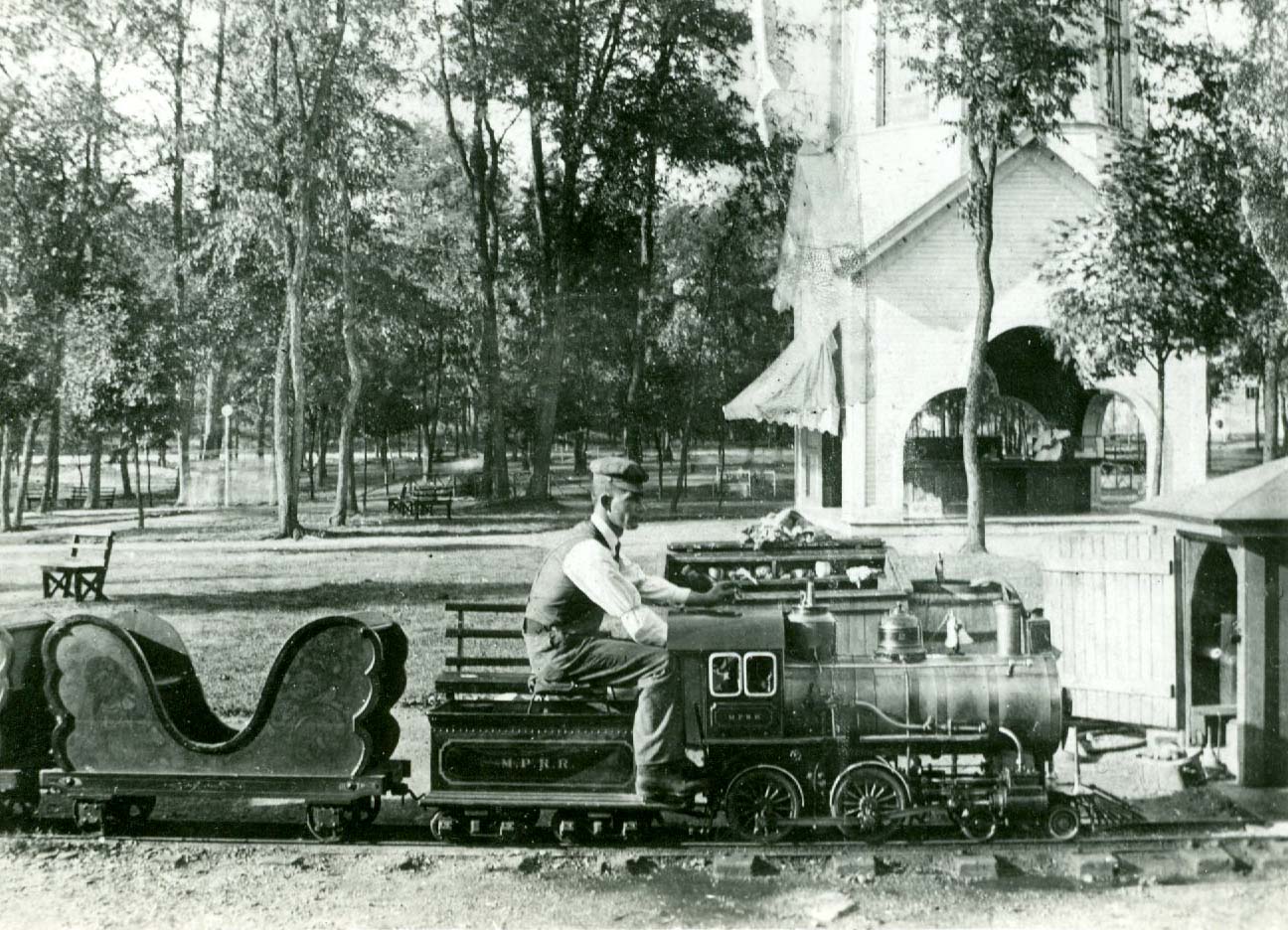

- Scattered throughout the park were several attractions. There was a small zoo with bears, monkeys and birds. An amusement section featured eight game booths and a shooting range. A miniature steam-powered 10-car train provided rides to adults and children as it meandered on narrow tracks throughout the park. The park also boasted a fish pond, playgrounds, street car waiting room and numerous picnic pavilions.

- One of the most popular draws at Monarch Park was a two-story dance hall. A u-shaped balcony overlooked the dance floor on three sides. The dance floor, according to newspaper accounts, was considered “one of the best in western Pennsylvania” with hardwood maple flooring and an elaborate layout of hallways. It was a common location for the Oil City and Franklin proms as well as wedding receptions.

- There was the Thriller roller-coaster, built at a cost of $25,000 in 1913. It was operated by way of consignment by a group of Pittsburgh men. It was reported to be the “exact replica” of a famous roller-coaster at Kennywood in Pittsburgh.

- A Whirlpool ride, also called the Aero Swing, offered swinging seats attached by chain to a rotating set of poles. It was built in 1913 at a cost of $10,000. There was also a small Ferris wheel in the park.

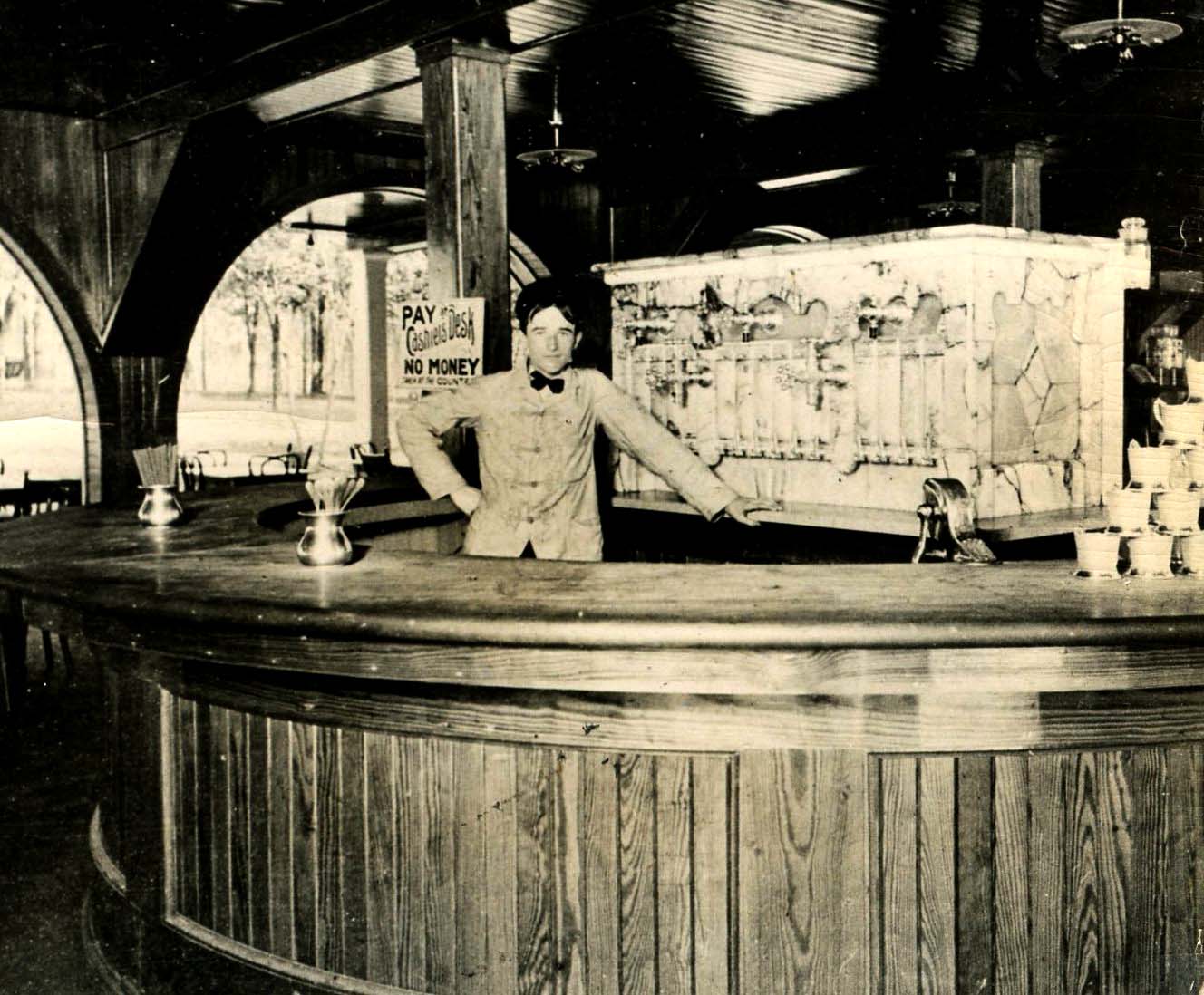

- A two-story restaurant dominated the Monarch Park setting. The second floor featured a full-service restaurant, described in advertisements as “plush” with fine linen tablecloths, cut glass and silver tableware. Dining reservations could be made by calling the Citizens Traction Co. office.

- When the Monarch Park season opened in June 1917, the trolley company announced that the famous Monarch Park Café chicken and waffle dinners would resume on opening day. The meals, starting at 5 p.m., would be served by five waiters. The cost was 60-cents with an extra 15-cents charged for ice cream and cake.

- A beverage and sandwich snack shop was located on the ground floor. A specialty was an ice cream cone. The park claimed to have made the first cones in this part of the country. The process entailed concocting the cone mixture in a skillet, removing the soft shell and wrapping it around a wooden cone-shaped form. A scoop of ice cream was immediately added to the cone shape which would cool and harden as soon as the ice cream was added.

- The park offered lockers for patrons who could store their picnic items as well as recreational attire.

- Elaborate gardens, many of them sunken, and manicured walkways were located throughout Monarch Park. There were also pavilions with the larger structures providing stage space for vaudeville acts, concerts and silent movie showings.

Written by Judy Etzel with research by Kay Dawson and design by Natalie Cubbon.

HIDDEN HERITAGE IS SPONSORED BY:

Oil Region Alliance

&

Gates & Burns Realty

Support This Project

Donations to the library are appreciated to help offset printing costs & make this project possible! Want to become a sponsor? Email us at promotions@oilregionlibraries.org to get started!

Make a Donation