Kramer & Mullins

- Judy Etzel

- September 24, 2021

- Hidden Heritage

- 3962

A pair of sturdy brick buildings in Oil City’s West End was the location of two very unique manufacturers at one time. The private companies would sell their one-of-a-kind products across the globe.

Those enterprises were very different – one served the oil industry and the other offered leisure to water enthusiasts.

They were the Kramer Wagon Company, a maker of sturdy wood wagons, and the Mullins Boat Corporation, manufacturer of fast and fancy watercraft.

Both companies claimed local ownership with numerous private investors stepping up to help fund the operations.

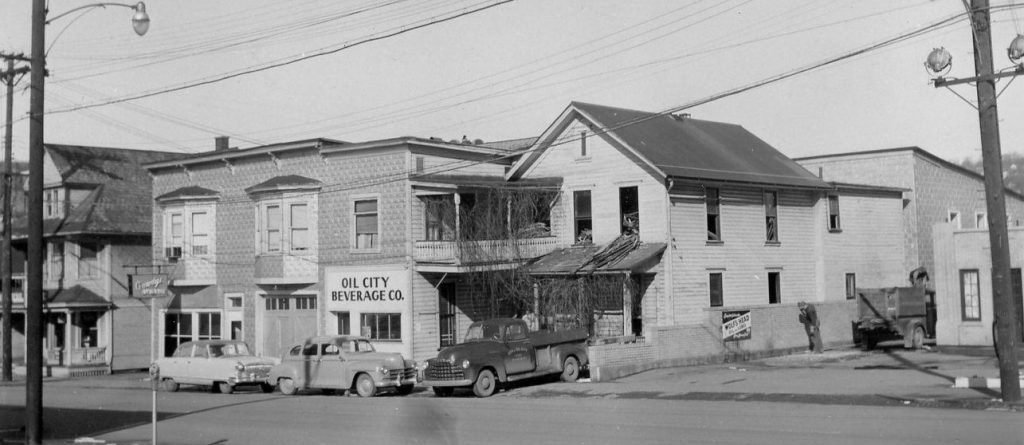

It all began with the construction of two five-story, 200-feet-long brick buildings at a sprawling West End property along the Allegheny River in 1891. It was the home of the Kramer Wagon Co. By 1936, the property had a new tenant, the boat company. The buildings would later include a variety of other tenants, such as truck equipment companies, a lumber firm and other small enterprises.

All business ceased at the property, though, when in Aug. 20, 1955, fire destroyed the complex. The spectacular fire was so hot that windows cracked, shingles melted and trees burned on several nearby properties along West First Street. The damages were estimated at $500,000.

Part of one of the tall brick buildings was saved and it became home to Crawford Industries. That building, too, was leveled by fire in 1963.

Kramer Wagon Company

William J. Kramer, born in Germany, moved with his family to the U.S. in 1845.

With a keen eye on the soaring petroleum industry further north, Kramer’s father uprooted his family and settled in Oil City where he set up a small wagon-making business on Seneca Street in 1861.

His son soon joined him in the business and it quickly outgrew its small shop because of a huge demand for wagons to haul supplies to the oil wells and oil to the market.

In 1880, Kramer joined with David L. Trax, an oilman, and the partners formed the Kramer Wagon Company. They opened up a large factory on Elm Street and were producing about 100 wagons a year.

By 1891, the business had expanded to such a degree that new quarters were required. Trax and Kramer hired contractors to build two large brick buildings in the West End to accommodate a larger manufacturing capability. The buildings were constructed between the railroad tracks and the Allegheny River.

At the time, the facility was the largest wagon factory in Pennsylvania. The partners reorganized their business and called it the Kramer Wagon Works. Trax was overseer of metal parts and accessories for the wagons and Kramer was in charge of all woodworking.

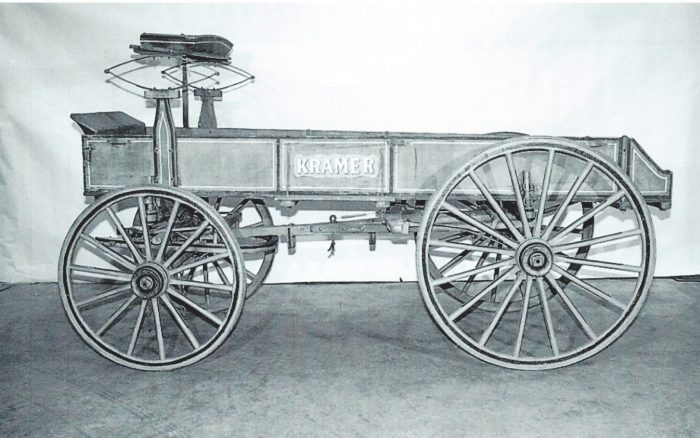

The product line boasted ten different sizes of wagons and the styles ranged from farm and lumber wagons to horse-drawn “trucks” for all manner of goods. In addition, the company produced fancy, elegant carriages for the city’s wealthier residents.

By the mid-1890s, Kramer Wagon Works was manufacturing 5,000-plus wagons a year. The wood of choice was hickory with all parts varnished and painted. The industrial product line also included wheelbarrows and wagon jacks.

During World War I, the Oil City company sold hundreds of wagons to the U.S. Army. The wagons were shipped to battlefield stations across Europe.

As automobiles became more popular, the company retooled its operations and shifted its focus from wood wagons to building trucks and auto bodies and offering repair services. By the early 1940s, Kramer Wagon Works was out of business and its former manufacturing plant was leased to a variety of businesses.

A Kramer wagon made in Oil City is on exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Oil City boasts a Kramer Avenue in honor of the wagon-maker. In addition, several brick homes built along West First Street were known as Kramer Wagon Works company homes.

The 2019 Grove Hill Cemetery tour booklet, “Oil City’s Buried Past,” notes the Kramer Mausoleum is located in the cemetery. Completed in 1904, the mausoleum was constructed from what was then the largest piece of granite ever taken into the cemetery. It required 14 horses pulling a heavy truck wagon to move the granite to Grove Hill.

Mullins Boat Corporation

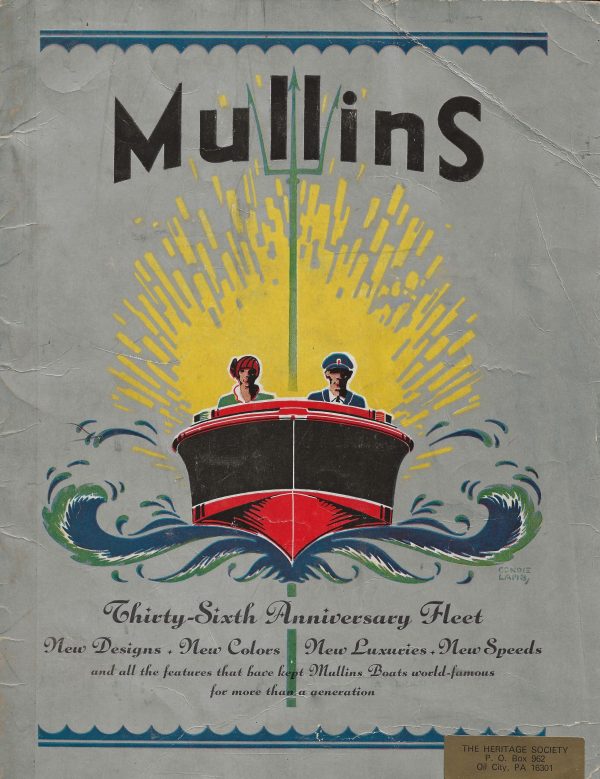

In late 1935, Leon Gavin, executive director of the Oil City Chamber of Commerce, learned there was an Ohio business for sale. Eager to help provide more jobs to the area, Gavin rounded up five local businessmen who wanted up to $100,000 to buy the molds and various boat-making equipment and tools from the Mullins Manufacturing Corp. of Salem, Ohio.

The maker of steel-hulled boats began operations with the manufacture of a duck-hunting boat in 1894. The company advertised it had produced “over a hundred thousand boats” when Gavin came calling.

The Ohio-based company had already been making headlines long before the move to Oil City. It was reported the Mullins steel-hulled lifeboats had traveled with Admiral Perry to the North Pole. At times, they were used as dog sleds on those journeys.

In addition, Czarist Russia had ordered several Mullins boats but the shipment was interrupted when the Bolsheviks during the Russian Revolution stole them and removed the engines to run sawmills.

Movie stars, too, apparently were keen on the steel-hulled boats with news stories noting Rudolph Valentino reportedly owned a Mullins speed boat.

As Mullins was transitioning to meet the auto industry demands, it scrapped its boat-making operations and sold the equipment, patents and more to Gavin and his fellow investors. The deal was specific: Mullins of Salem did not sell the stamping presses and dyes, at first, to Oil City. Salem continued to produce the stamped hull and deck and then shipped them to Oil City for assembly. Later, the Oil City plant eventually took on more of the manufacturing end.

Fifteen railroad cars were loaded up and sent to Oil City where the materials were set up in a building next to Kramer Auto Body, formerly Kramer Wagon Works, at Abbott and West First streets.

In March 1936, production began with an employee roster of 75 men. The state issued a charter for the new Mullins Boat Corp. on April 6, 1936.

Officers in the new company were Gavin, W.A. Royston Jr., J.D. Trax, A.E. Mackintosh and J.E. Burns. The stockholders introduced the plant to the public during a joint luncheon in May 1936 of the Oil City Rotary, Kiwanis and Lions clubs.

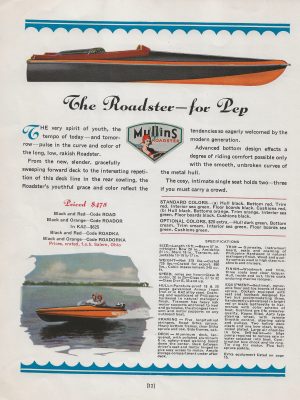

The visitors were told the Mullins boats were “America’s most beautiful pleasure craft, brilliantly colored in enduring marine lacquer and offering flashing speed, luxurious comfort, lifeboat safety with indestructible, puncture-proof, leak-proof, unsinkable hulls of corrosion-resisting metals for salt and fresh water service.”

Did You Know?

Speaking of boats and the river, here’s a little bit of history:

In the spring of 1930, several Oil City men reported to authorities that someone had been setting off dynamite in the Allegheny River over the weekend. There were a number of dead bass and salmon in “the best of the river – most of the dead fish were found in the big eddies at Rockmere and Walnut Bend,” noted a newspaper article. The news item noted: “That there were salmon weighing fully seven pounds and bass more than four pounds shows the wanton slaughter of game fish. Considered poachers, so authorities are investigating.” Meanwhile, a photograph and article also published in the spring of 1930 attested to the presence of salmon in the Allegheny River. J.H. Gray of Oil City is shown holding a salmon he took while fishing in the vicinity of the Oil City Water Works in company with Edward McLaughlin, also of Oil City. The fish measured 25 inches in length and weighed just over seven pounds.

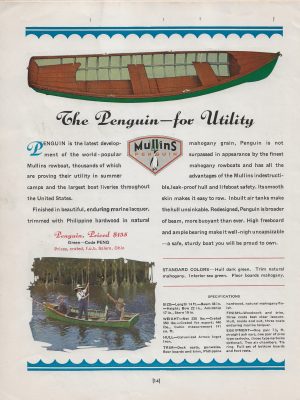

The watercraft product line included pleasure boats, duck hunting boats, row boats and inboard launches. Each craft, available in many colors, carried a one-year guarantee. Prices would range from $795 for the Sea Eagle Deluxe with a 45-horsepower engine to $135 for the Penguin utility rowboat.

The Mullins boats were far better, insisted the company owners, than rival boat-makers because the all-steel vessel did not need a boat house, cover or shelter of any kind and, unlike wood boats, had “no seams to open, nothing to warp, rot, check or split, no occasion ever to wait for the boat to swell up before it is water-tight.”

“While others are spending valuable vacation time on shore caulking and tinkering with their boats to make them watertight and usable, Mullins owners launch theirs and glide away without the loss of a single golden moment,” advertised the company.

Each boat featured heavy oak bottom frames and side frames, galvanized iron plating, heavy oak motor supports, mahogany trim, full-length seats with lazy backs and numerous air chambers to make them non-sinkable.

The Oil City plant owners decided to concentrate on manufacturing the Sea Eagle (Deluxe, standard and sportster models, all inboards) and rowboats the Gull, Drake and Swan with outboard motors. A few other models were also made as orders came in.

One of the first boats produced at the Oil City plant was a power boat sold to the Keystone Public Service Co., Oil City’s transit company, for use in case of an emergency on the Allegheny River.

Company records show two famous designers – Julius T. Herbst, water racer and boat designer, and Count Alex de Sakhonoffsky, world-famous auto designer – worked for the Mullins corporation during the 1930s. They worked together to design the popular Sea Eagle inboard model, made in Oil City.

In addition to boats, the Oil City plant also sold accessories ranging from cushions for gas tanks, oars, anchors, storm curtains and more. Two models of boat trailers, too, were for sale.

The local boat maker garnered much publicity in 1939 because of an unusual order. On Aug. 12, 1939, an order for three boats for King Farouk of Egypt was received at the Mullins plant by cable from Cairo.

The cable stated: “Dispatch Alexandria, Egypt, within 10 days, very urgent, for his Majesty King Farouk, one Gull outboard, one Duck rowboat, and one Swan rowboat; all as per catalogue, with oars and fully equipped.”

It was one of numerous foreign orders filled by Mullins. In addition, municipal boating areas such as New York’s Central Park featured the all-steel rowboats.

Locally, though, not many Mullins boats were purchased because they were considered too heavy and had too deep a draft on local waterways. A 1978 newspaper story quoted Mullins boat owner and Tionesta cottage owner Merle Hodge of Oil City as saying, “The boat was too heavy, banged on the bottom a lot and during a hard rain it would fill with water and sink at its dockside.”

By 1942, the Mullins Boat Corporation of Oil City had dissolved and a new company, the Champion-Mullins Corp., was incorporated. The local plant continued to market the Sea Eagle model into the mid-1940s.

World War II, though, derailed the boat company because of difficulty in getting steel for the hulls. The company stayed in business, changing its main production line to steel folding cots and pontoons for military floating bridges for the armed forces.

The Champion-Mullins Corporation officially closed up in June 1961.

Support This Project

Donations to the library are appreciated to help offset printing costs & make this project possible!

Make a DonationWritten by Judy Etzel with research by Kay Dawson and design by Natalie Cubbon.