Music, Literature and Faith

- Judy Etzel

- September 10, 2021

- Hidden Heritage

- 2780

The 2021 year was a time to celebrate several anniversaries of well-known institutions in Oil City, a city that was itself marking its 150th anniversary of incorporation.

The anniversaries called attention to the longevity of music, literature and faith.

Here are four of those anniversaries:

Oil City Library

The Oil City Library, launched informally by local citizens as the Petroleum Institute in 1864, took on a new name and a more expansive mission when supporters reorganized it in 1871.

The local institution, marking its 150th anniversary in 2021, was renamed the Oil City Library Association. It would get its biggest boost in 1888 when women of the city formed the Belles Lettres Club. And it would be women of the city who would lead efforts to establish a full-fledged collection of reading materials and arrange for a magnificent building to house those items.

Their mission would be thwarted several times during the early years.

Here’s how it happened:

Slowly but surely amassing books, the Oil City Library Association and the Belles Lettres Club stored the materials in rooms in the First National Bank building and eventually the Trax and Kramer building on Seneca Street. By 1875, though, hard economic times hit the region and more than 1,000 books were sold off to pay back rent. Still, the Library Association kept up its efforts to provide free reading materials to city residents. Small rooms were rented in various buildings to house association books.

It was the formation of the Belles Lettres Club that re-invigorated the drive to establish a library. The all-women club had as its sole intent to establish a public library.

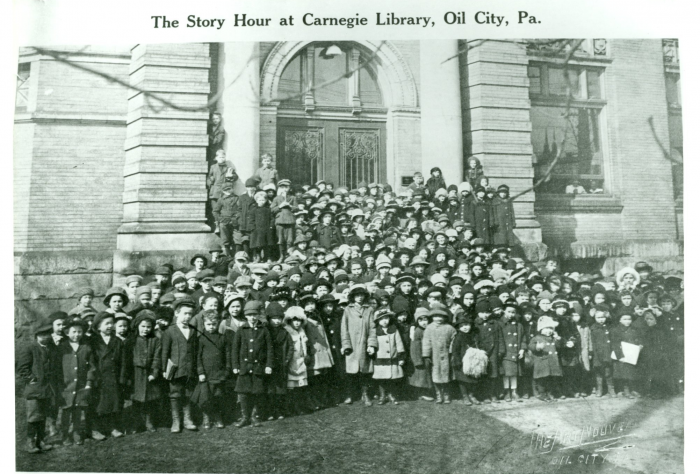

By 1900, the club had a collection of more than 5,000 books. Aware that steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie of Pittsburgh was donating money across the nation to build free public libraries, the Belles Lettres club formally asked Carnegie for funds to build a library in Oil City.

Carnegie agreed and offered $44,000 to build the facility. There was stipulation, though: local citizens must provide the site and $3,000 a year to pay for library operations. City council turned down the request for the annual stipend and that sent the library proponents to ask for a public vote on the matter.

There was opposition to the library plan in some quarters. The arguments against the project included:

- If Carnegie was so excited about establishing a library here, he could very well endow it to guarantee its future.

- Some said they were upset that fictional books would be permitted on the library shelves, claiming “it would provide the ruination of hundreds of young persons … by reading cheap sensational novels.”

- Another anti-library resident insisted he was tired of hearing about the library and all its resources, adding, “We know too darned much as it is.”

There was great talk that if the library referendum failed, Carnegie would make the same offer to the City of Franklin for the construction of a library building. In favor of a new library building, the Blizzard newspaper editorialized, “Oil City can stand all the institutions of learning she can get, and then some.”

The vote to accept Carnegie’s offer was 982 for the project and 466 against it.

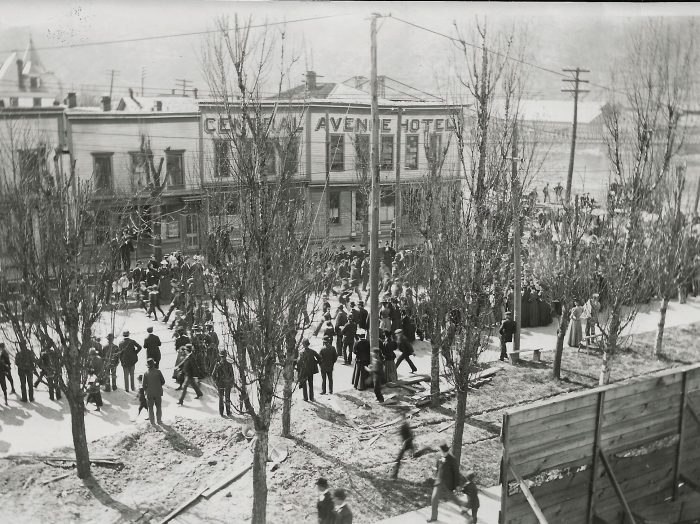

Through public fundraising, the Belles Lettres Club and the Oil City Library Association raised $11,500 to buy property for the new library building. Three sites were checked: property owned by Oil Well Supply on Seneca Street; the Shively property at Graff and Colbert; and the James property on Central and Front. The choice was the James property, decided by giving one vote per $1 donated by local residents.

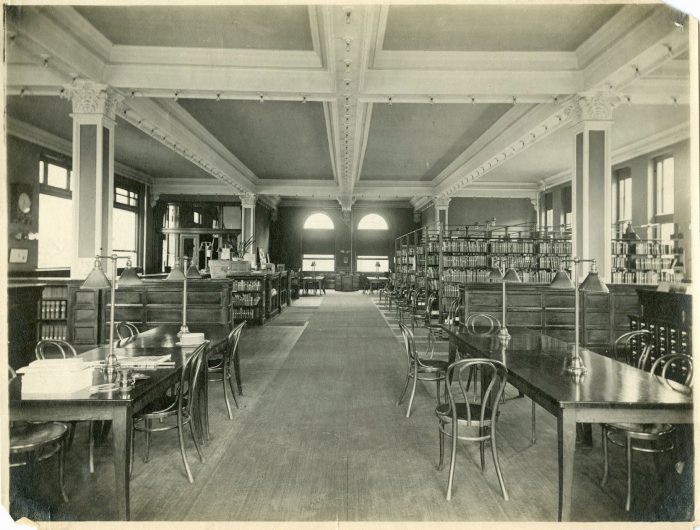

Construction began in 1902 and the new Carnegie Library was opened with much fanfare on July 6, 1904. The building has been expanded and remodeled over the years.

In 1958, the name was changed to the Oil City Library to correct the notion that the institution was endowed by the legendary steel tycoon’s estate.

First Free Methodist Church

A longtime Oil Church traces its beginnings to a couple’s bad investment.

The First Free Methodist Church at the corner of Wilson and East Third streets is marking its 150th anniversary in 2021. It began in 1871 as a camp meeting led by a husband and wife team whose investment in the booming western Pennsylvania oil fields went bust.

Mr. and Mrs. Hiram A. Crouch had hoped to raise enough money to fund a church seminary in Rochester, N.J., where they owned a farm. They lost their investment, though, and decided in 1867 to travel in person to the oil fields. Hiram took a job with the Columbia Oil Co., a business owned by Pittsburgh investors. Columbia Oil owned the Story farm property which quickly became a small but thriving community of employees and their families.

In that community, the Crouches opened their home for Bible studies. The small congregation identified itself as being associated with the First Free Methodist movement.

According to the church’s history, the gatherings grew into camp meetings held in nearby communities in an effort to spread the faith.

In 1871, a camp meeting at Lee’s Hall on Oil City’s South Side was so successful that it prompted those in attendance to call for the organization of a Free Methodist Church.

A church history reported that the Crouch couple’s bad financial difficulty had evolved into a great success: “Instead of becoming bitter, they used this financial misfortune to refine their souls,” noted the history.

The Oil City-centered congregation met in a variety of meeting halls until deciding in 1881 to buy a vacant lot on East Fourth Street. A wood frame church was dedicated as a worship center in 1884.

Over the next 20 years, the Free Methodist Church grew and some of the credit for that is owed to the nationwide revival movement. Rev. R.H. Bentley, a Franklin businessman and an interim pastor serving churches in Oil City and Franklin, hosted many revivals at the Oil City church. He was described as “pre-eminently a soul-winner” and drew very large crowds to the church.

News accounts also credit 21-year-old Rev. A.C. Showers for expanding the Free Methodist Church by way of a series of winter revivals “that stirred the entire city.” Vivien Dake organized Pentecostal bands that traveled to public events to spread the gospel.

It all led to the congregation building an addition to their wood church but it was not large enough to accommodate the growing revival crowds. By the early 1920s, the church members opted to raise money to buy a lot at the corner of East Third and Wilson and launch a campaign to build a new church.

The new red brick church was dedicated in the spring of 1924. On the dedication day, church pastor Mendal Miller told the congregation that another $25,000 was needed to fully pay off the new church.

“In 30 minutes, cash and gilt-edged pledges were received amounting to $26,530. As in the building of their tabernacle, the people could hardly be restrained,” noted a newspaper editorial. “It was a fine specimen of quiet hilariousness. If the Lord loves a hilarious giver, the good Free Methodists of Oil City must be the special objects of His affectionate regard.”

In later years, the congregation bought the adjoining lot and built a parsonage and parking area.

Good Hope Lutheran Church

The wave of immigrants that poured into Oil City as the oil boom and the later aftermath of the Civil War prompted the founding of a church that reflected German heritage.

The Good Hope Lutheran Church at 800 Moran St. was organized in 1871 by German immigrants who wanted a church of their own. The 2021 year marks the 150th anniversary of the church founding.

The first congregation numbered about 50 members who met in rented halls throughout the city until the construction of a small frame church on East First Street. It was called the German Good Hope Evangelical Lutheran Church, formally chartered and incorporated in 1871, conducting all its services in German. By 1888, the church roster of members was at about 300.

That same year, several members lobbied for the church services to be conducted in English. There was a brief compromise with the morning worship services conducted in German and the evening services that used the English language.

Church records show many members believed it was imperative, with the church quickly growing, that the English language be introduced into the church services. At that point, the minister told the congregation his bi-lingual skills were not sufficient to conduct services in English and he tendered his resignation.

Opposed to a change that would make English the dominant language for church services, a group of dissenters withdrew their membership and formed what would become Christ Lutheran Church.

In 1901, church members voted to build a new church on the former Brundred property at West First and Petroleum streets. The impressive reddish brick church was dedicated June 14, 1903. Three years later, the church debt was retired as a result of “the gifts of her people.”

An aging church and a growing membership prompted a search for property with the intent to build a new church. In 1963, the congregation bought the Barnes property that consisted of six acres in Oil City and 12 adjacent acres in Cranberry Township. M.C. Strickland & Sons of Oil City constructed the church. The building cost was $500,000. The church on Moran Street was dedicated in 1966.

The former church building was demolished and is now a parking lot. The parish hall and parsonage next to it were built in 1927 and are now private residences.

Schubert Club

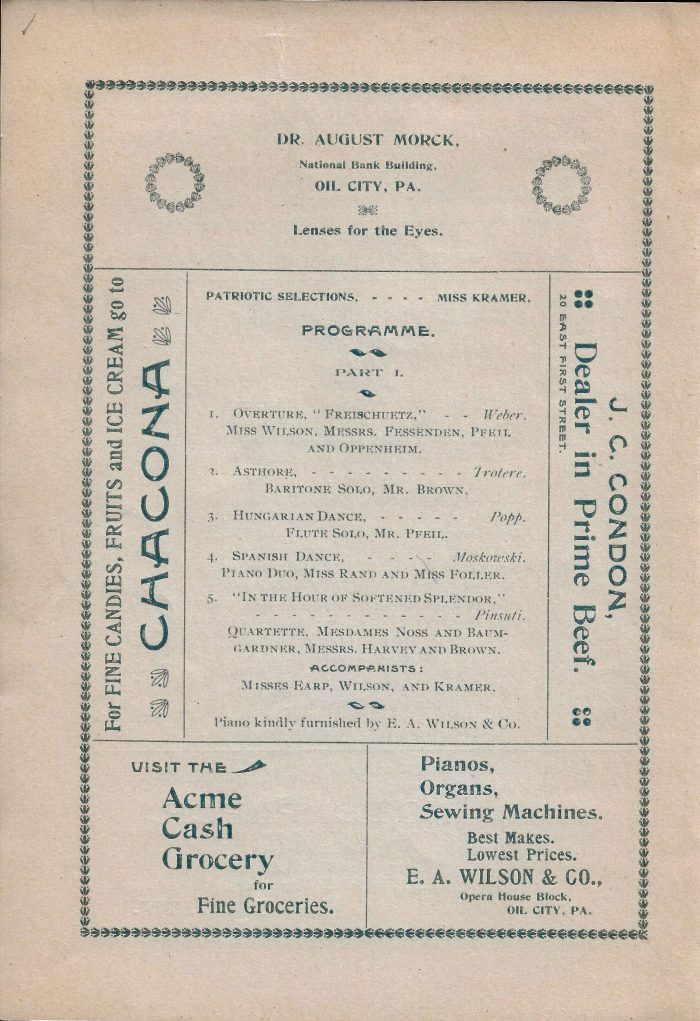

Schubert Club, a music and literary appreciation and performance organization, is marking its 125th anniversary in 2021.

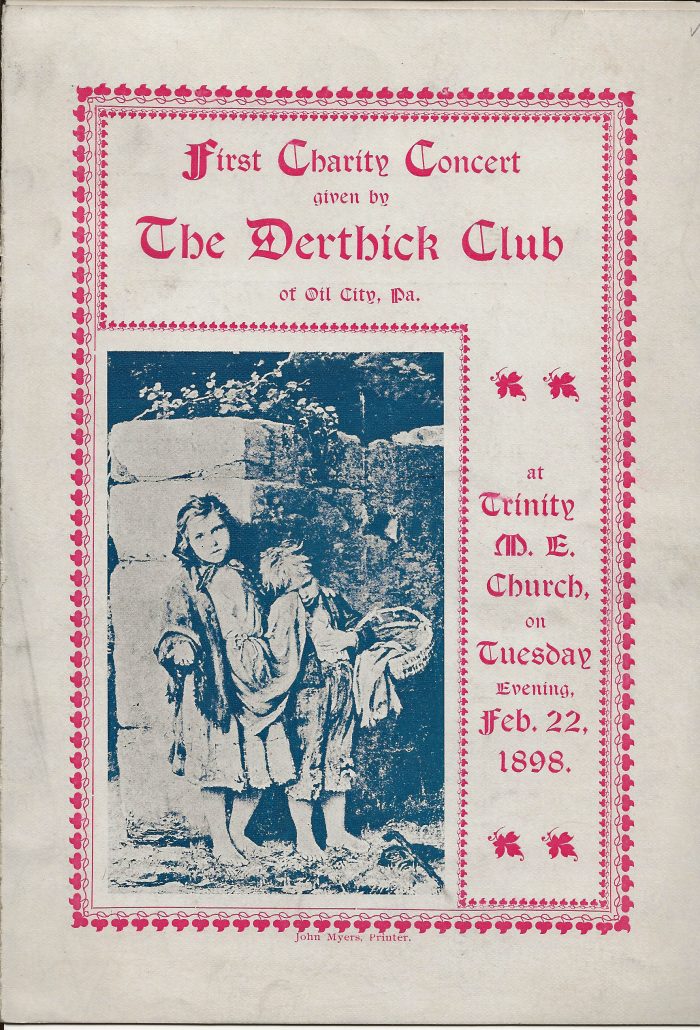

The Oil City group started out with an unwieldy name given to it by a man who wanted to go down in history in his hometown. The club started Oct. 19, 1896, as the Derthick Musical and Literary Society.

Club records show a “Mr. Derthick”, a fellow from Chicago, founded the organization “with the express purpose of founding a branch to an organization which bore his name in his hometown. … It was his desire to expand music and literary appreciation to small towns located far away from urban and presumably more sophisticated cities.”

Originally, membership was limited to 20 adults in order to be able to meet in members’ homes. One bylaw noted members would be fined 25-cents if they were late to a meeting and twice that amount if they “failed to attend or to take part in an assigned program.” The charter members were all women save for one intrepid man.

The goal was straightforward: to promote the understanding, study and performance of fine music and to encourage talented young people to continue their education in music.

One early club project was a “charity concert” promotion that was designed to encourage interest in classical music for “city residents of little financial means.”

In 1898, club members voted to change the name to Schubert Club and drop the unwieldy Derthick moniker. The membership was expanded and the meeting sites changed from private homes to Jessie McGill’s piano studio and then later to the old YMCA’s meeting room in Foster’s Hall, the Carnegie Hall upstairs in the library and eventually to the present meeting place of the Belles Lettres Club.

Membership faltered over the next few years and that prompted the Schubert Club board to send out stern letters to members, directing those who were vocalists or musicians “to learn at least one new number during the year rather than substitute with old numbers, as we frequently have done, as entertainment rather than education seems to be the prevailing feature of last year’s work.”

By 1910, the club was again flourishing and membership had grown past 50 people. That year, Schubert Club joined the National Federation of Music Clubs and splurged for a new grand piano for its meeting site. Three years later, the club established a new organization for students. Called the Junior Schubert Club, it is recognized as the oldest junior music club in Pennsylvania and perhaps in the U.S.

Support This Project

Donations to the library are appreciated to help offset printing costs & make this project possible!

Make a DonationWritten by Judy Etzel with research by Kay Dawson and design by Natalie Cubbon.