One of a Kind

- Judy Etzel

- March 4, 2022

- Hidden Heritage

- 7254

Thrills and skills combined frequently in the prosperous Oil City and surrounding area as daredevils, stuntmen, tricksters and others made headlines for doing something unusual.

Tree-sitting? We had that in Oil City. Scaling tall buildings while blindfolded? Yup, had that too. Balancing on airplane wings? Yes, that happened here. Tightrope walking over the Allegheny River? That feat is in the books. Traipsing barefoot over a snow-covered bridge? It made headlines. Skip-roping to a new record? That, too, drew attention.

Here’s a look back at the unusual one-of-a-kind endeavors that claimed Oil City as a tagline for where and what happened.

Barefoot in the Snow

Theodore “Bud” Plaginos, born in 1917 in Johnsonburg, PA, lived with his family in Franklin where he graduated from high school in 1935. He went to Penn State and married his high school sweetheart, Mary E. Beichner of Franklin, on May 30, 1940.

After working for a while at CPT in Franklin, Plaginos enlisted in the fall of 1943 in the Navy and was assigned to the Seabees in the Asian-Pacific Theater in World War II.

A.M. Turney of Oil City wrote Plaginos overseas and one piece of mail was a holiday card that depicted hometown scenes after a record snowfall. Plaginos answered the letter and vowed, “When I get back, I’ll never again gripe about how cold it is to walk across … (the bridge) in the dead of winter. I’d do it barefooted if they send me home.”

The young sailor came home on Dec. 10, 1945, for a short leave. He joined his wife in their home at 111 E. First Street in Oil City. His parents, too, had moved to Oil City and lived at 352 Seneca Street. They owned the Sandwich Shop at 317 Seneca Street.

On Jan. 23, 1946, Plaginos put on his Navy uniform, walked to the State Street Bridge (now Veterans Bridge), took off his shoes and walked barefoot in the snow on the pedestrian walkway.

A photographer from The Blizzard newspaper, Oil City’s evening newspaper, snapped the photograph and shared it with the Wide World photo service. The picture was transmitted via a national wire service and printed in dozens of small and large newspapers across the U.S.

His daughter, Pamela McLaughlin, recalled many years later that he had an enormous response from people across the country. The letters included marriage proposals, job offers, pen pal requests and thanks for his military service, she said.

After the war, Plaginos worked as a pharmaceutical representative. He and his wife and daughter, who was born in Oil City, lived for a while in Oil City and eventually moved to Florida. He died in 2001. Funeral services were held in Oil City where he is buried.

Climbing High

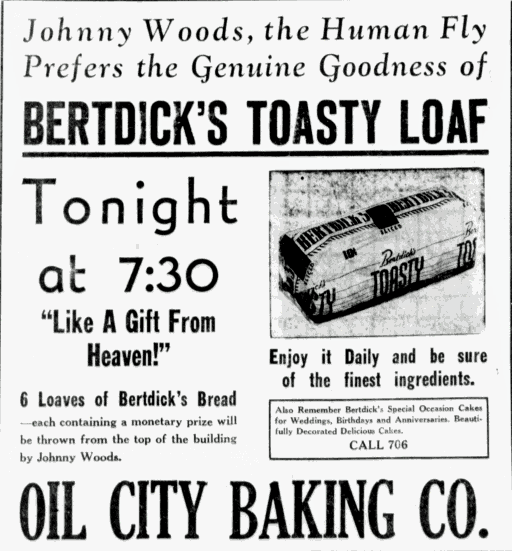

In mid-July 1939, a huge crowd gathered near the railroad freight yards along the Allegheny River, the site now of a hotel and Justus Park, to watch Johnny “the Human Fly” Woods scale the five-story Fair Building across the tracks.

The 42-year-old, whose escapade was funded by a variety of product endorsements from local merchants, didn’t simply climb the building. His crowd-pleasing act included having his wife sit on his shoulders as he walked around the top rim of the building. He also rode a bicycle around the rooftop rim and then balanced on two chairs at the edge.

And, he did it blindfolded.

“Woods bases his successes on strong muscles in his arms and feet, giving him a powerful trip and powerful leg muscles,” boasted promotional ads for his appearance. Woods, a Kansas resident, started his career as a flying act in vaudeville. He soon was scaling tall buildings across the U.S. In 1939, he had already climbed the 915-foot-high Woolworth Building in New York City, the 535-foot-high William Penn statue in Philadelphia and numerous multi-story buildings in Boston, Los Angeles and San Francisco.

In his 1939 visit to Oil City, Woods profited from endorsements from Buick, Wolf’s Head, Bertdick’s Toasty Loaf bread and others. The W.T. Grant store gave him their branded overalls which Woods was “wearing as he allowed himself to be supported out over the roof by means of a pair of them.” The Sears & Roebuck store provided the bicycle for his “ride of death along the cornices.”

“His iron grip and tennis shoes are all that he has in his climb,” noted the newspaper. “No ropes, for they may break.”

In 1955, Woods, who by then had climbed “about 5,000 buildings with only seven falls on record” returned to the area and climbed the four-story Emil Long Furniture building in Emlenton. His visit there was sponsored by the Emlenton Volunteer Fire Department and, in return, cash donations from patrons watching his show were split with the department. He also climbed the Fryburg Hotel.

Crossing the River

J.B. Allen, a Michigan native, was a pharmacist/first class chemist, who worked in Drs. Colbert and Egbert drug store in downtown Oil City. An 1864 Oil City Register newspaper advertisement refers to him as employed by the Reynolds and Colbert Pharmacy, also in Oil City.

John J. McLaurin wrote in his “Sketches in Crude Oil” that Allen was highly educated and “could read Greek as readily as English, declaim in Latin by the hour, quote from any of the classics and speak three or four modern languages.”

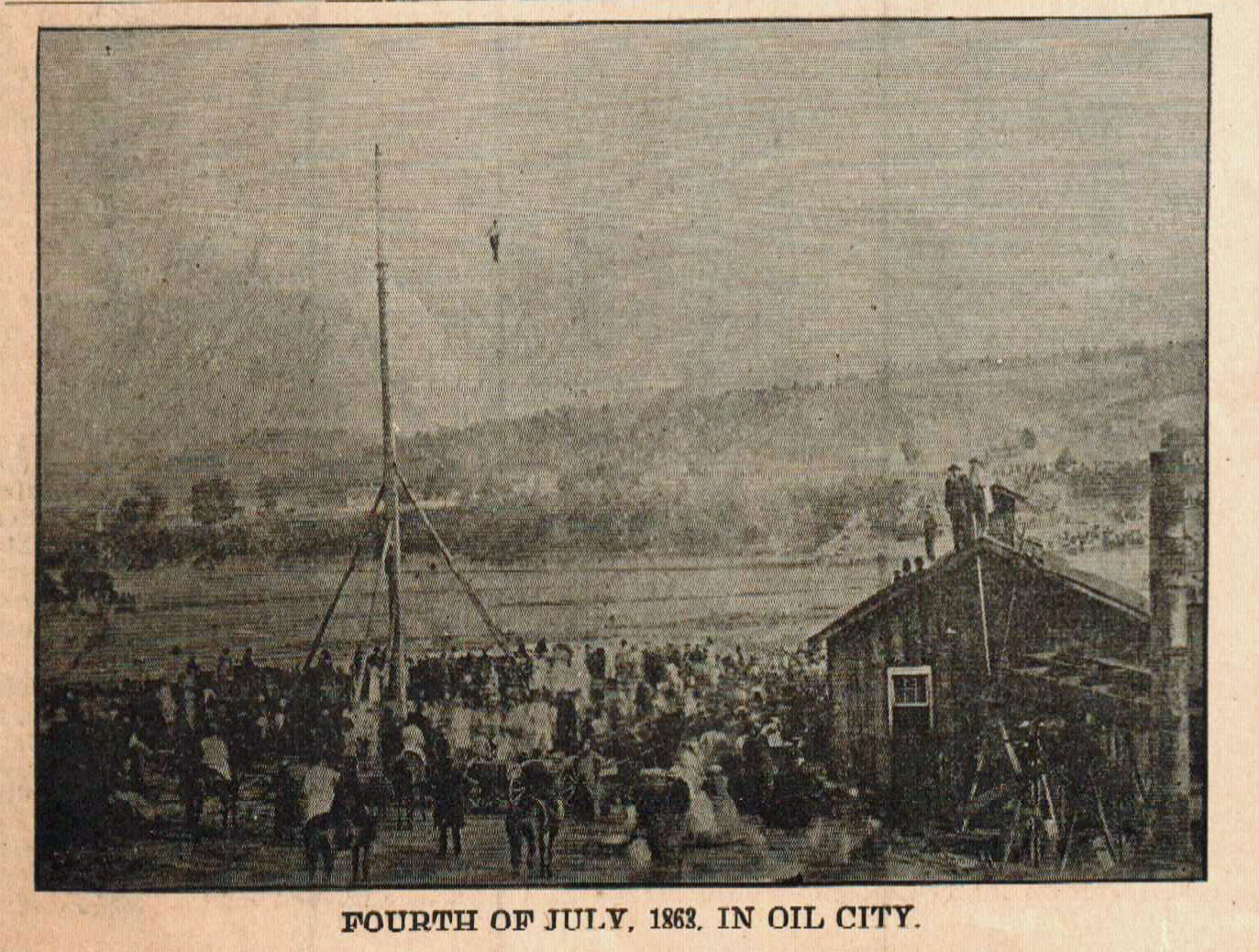

Allen, though, had a chore he had to do – raise money to pay off a mortgage on his father’s farm. To do that, he conceived of a money-making plan set for July 4, 1864, in downtown Oil City. He announced he intended to walk across the Allegheny River on the metal wire strung to accommodate the ferry crossing.

The wire, one-inch thick, was about 90 feet above the river surface and was 300 yards long.

“We can’t say we are in favor of exhibition of this kind, but as there is a feverish anxiety on the part of a great many to see a person run the risk of breaking his neck, we suppose there will be a large attendance,” wrote a reporter in the Oil City Register newspaper on June 30, 1864. “The gentleman should be well paid for his performance and we hope those who enjoy the sight will be liberal toward the individual who risks his life for their gratification!”

Allen carried a flag, mounted on a pulley wheel in front of him, with one hand and a balance pole in the other hand. He successfully completed his tightrope walk but it is unknown how much money he gathered to pay off the mortgage. Deming’s Gallery, a local photo studio in Oil City, quickly ran newspaper ads noting it had “a splendid picture of J.B. Allen walking the wire cable” and they were on sale at the shop.

In McLaurin’s account of Allen, he describes him as “eccentric and the hero of unnumbered stories.” One story involved a horseman rushing into his drugstore and asking that a prescription for a “deadly poison” be filled. Allen resisted, saying it was not safe to fill the prescription but the customer insisted.

Allen filled it and wrote on the label: “if any dam fool takes this prescription, it will kill him as dead as the devil!”, wrote McLaurin.

Champion Jumper

Frederick A. Connor, born in 1875 in Rockland, attended St. Joseph High School and Notre Dame University. He worked at one time as circulation manager of The Derrick newspaper and later owned a newspaper distribution business in Oil City. He and his family lived on East Second Street.

Connor, who died at the age of 88 in 1964, was a well-known track coach, cross-country runner, and track star who won numerous championships and set many records. At the Oil City YMCA, Connor set all-around strength and endurance records in record times.

He won varsity track letters at Notre Dame and was recognized for his overall athletic feats with two portraits that hang in Rockne Memorial field house at Notre Dame. He also coached track at Westminster College.

But it was another skill that brought national fame to the Oil City man.

William Plimmer, an English boxer, decided to set a record in the mid-1890s for jumping rope solo. He posted 3,926 consecutive jumps without a miss or a pause.

That intrigued Connor in the U.S. who was spurred to do better in a desire to break the record and make it an American all-time feat. He did that, skipping 4,035 times at a location in Oil City. The record was duly noted and that prompted another challenger, whose name is unknown, to list 5,000 skips in one hour.

On March 1, 1896, Connor bested that by skipping 7,000 times in one hour and 45 minutes.

More challengers appeared and Connor again exceeded his own record, skipping 2,000 times in 14 minutes and 20 seconds at an event at the Oil City YMCA in December 1897. He beat that feat a few days later at a performance in the Oil City Athletic Club.

According to his 1964 obituary, Connor’s final skipping contest saw 10,111 skips without missing a beat and that record gave him national champion status.

A Ripley’s Believe-It-Or-Not cartoon years ago showed Connor as the world record holder for rope skipping.

Daring Aerial Tricks

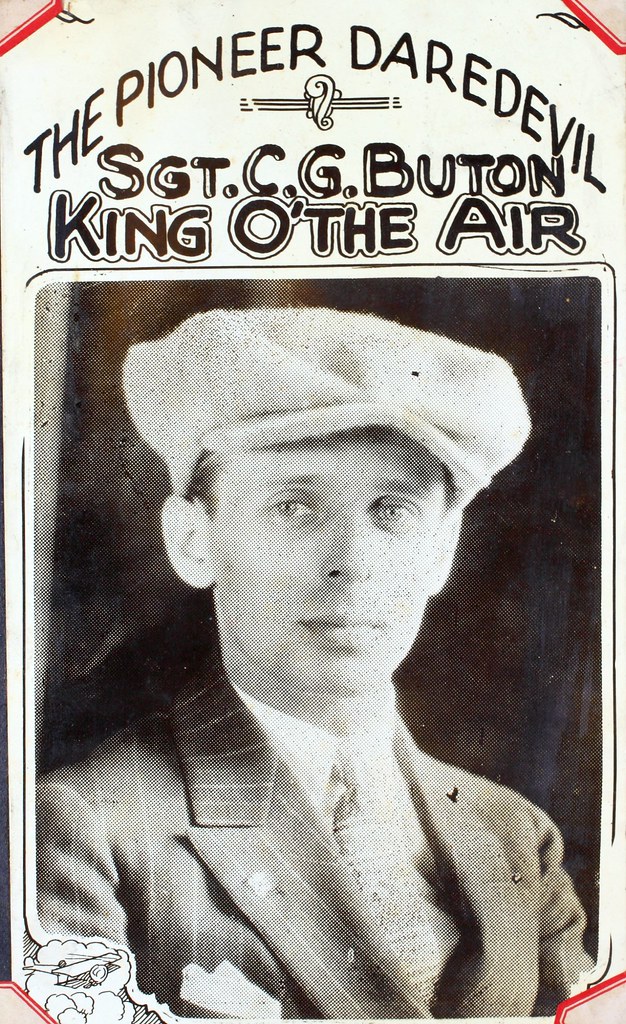

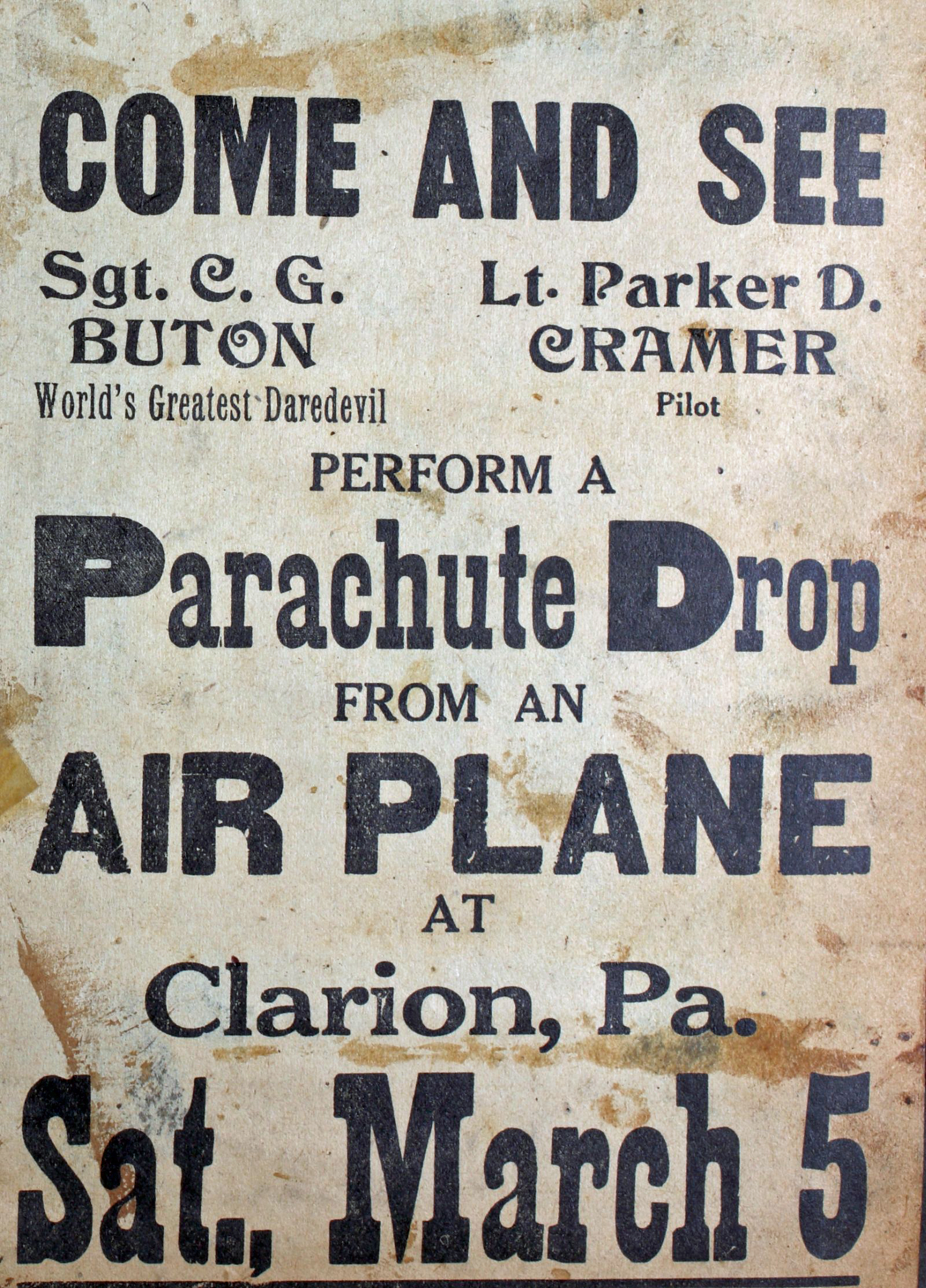

Carter Buton was the son of Albert and Esther Buton of Pearl Avenue in Oil City. His dad was employed by Seep Brothers in Oil City and later the Oil City Trust Co. Young Buton enlisted in the Army Motor Transport Corps in May 1917, during World War I. He was quickly transferred to the Army’s Aerial Service where he reportedly “tested every parachute that was sent to U.S. balloon and airplane forces overseas.” He was discharged in October 1920.

After the war, Buton did aerial advertising for large manufacturers and fairs. His interest, though, soon turned to more adventurous work. He became involved with the ABC Flying Circus and soon was featured as an aerial stuntman.

In the first six months of 1921, Buton was the key performer in an aerial show that toured small towns and large cities across the northeastern U.S. The tour in April included Oil City, Clarion, Franklin, Brookville, Kittanning and Punxsutawney.

Buton was known for having “five sensational acts” that included wing walking, aerial trapeze stunts, parachute jumps, plane changing and a leap for life. The latter trick involved jumping with a parachute out of a plane at 5,000 feet while the airplane was traveling at 100-plus miles per hour.

“A former Oil City boy, who in his boyhood days chased the elusive nickels just as keenly with the call ‘Blizzard’ as he now goes after the dollars by taking his life in his hands doing stunts in mid-air,” noted The Blizzard afternoon newspaper in Oil City in a story about his local appearance.

In one show, he was photographed being handcuffed by a police chief in the home city and went on to wing-walk while wearing the cuffs.

His pilot during the local performances was Lt. Kramer, described as “a former member of the aerial police force of New York City Police Department.”

Promotional ads described Buton as “the pioneer daredevil” and “King of the Air” and master of his “famous death drop which is thrilling and almost hair-raising to watch.”

Buton performed that stunt in the Oil City show by dropping, by parachute, “into the very heart of town,” noted the newspaper.

The aerial show was free to spectators, courtesy of sponsorships by “a number of public-spirited businessmen of Oil City.”

Buton and his family collected news clippings of his aerial escapades and compiled them in a scrapbook. Those materials are now in the San Diego Air and Space Museum archives.

Carter Buton later worked as a general agent for an outdoor carnival in Missouri and an advance agent for a carnival company. He died in 1971 and is buried in Kansas.

Sitting in the Tree

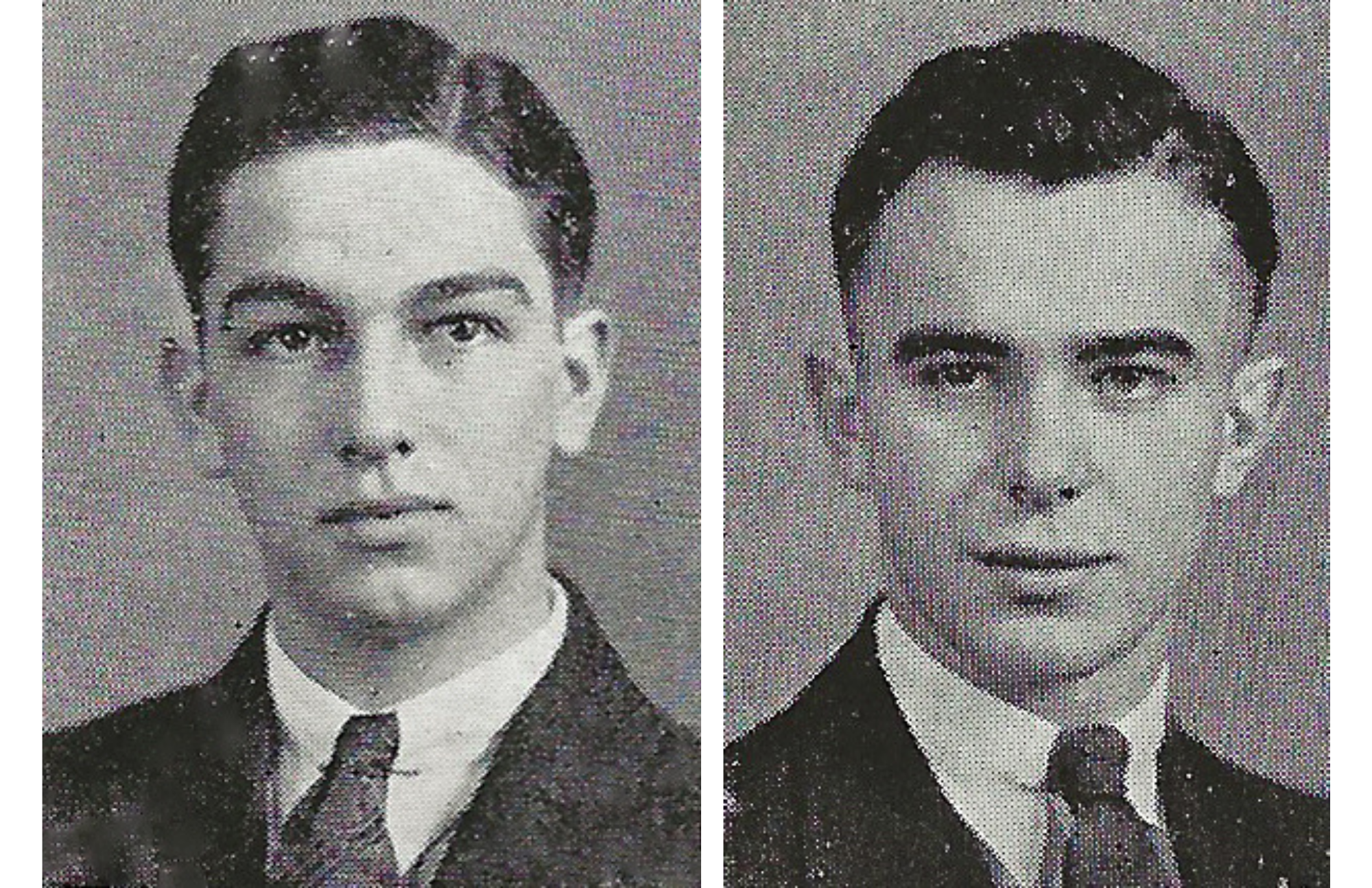

Two 1934 Oil City High School graduates drew national attention in the summer of 1930 for testing their endurance by sitting in a tree house for 18 straight days and nights. The oak tree Varnes Borland and Norman Gotham climbed was on West Third Street between Mayer and Cowell.

The Junior High students spent July 27 to August 15 up in the tree in an effort to mimic a nationwide trend of tree-sitting and flagpole-sitting. Their endurance test was highly publicized.

There was a ground crew, in the form of school pals Clayton Bouquin and Jack Goodrich, who hoisted meals and water up to the teenagers. They also supplied sufficient water for the two to occasionally bathe. A pair of mattresses were uplifted to the tree house. Their shelter was a tent perched on a wood platform up in the tree.

According to news reports, a local milk company supplied them with fresh milk while sweets, ice cream and pastries were sent by Cribbs Market and Jerko’s Ice Cream Store, both on the South Side. The sitters enjoyed a radio sent up to them. A green market basket served as a dumbwaiter.

A barber climbed the tree at mid-stay and provided haircuts. He was Charlie Meddock. Some residents made home-cooked meals and hoisted them up the tree.

The two boys finally decided to quit their endurance test because, as Borland said at the time, “All kinds of people were offering us so many things,” he said, listing the offers as boat rides, parties and more.

DID YOU KNOW?

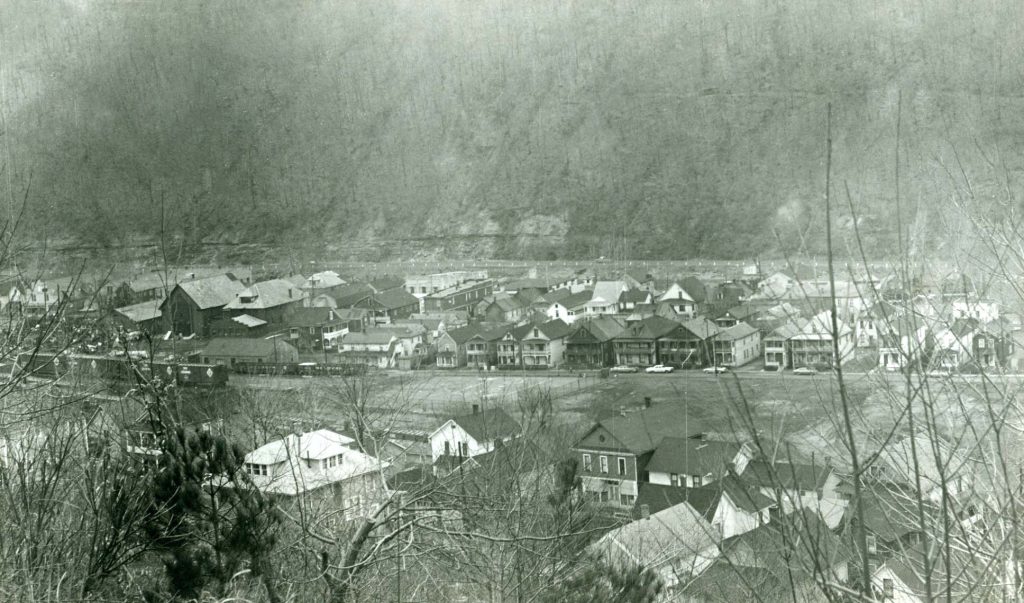

Oil City can claim a remarkable heritage derived from a steady and strong stream of immigrants over the years. One sizable immigration origin was the Ukraine in Eastern Europe. The newly arrived individuals and families were predominantly Catholic or Jewish and settled into neighborhoods throughout the city.

One neighborhood comprised of just two streets – Standard and Sevens streets – boasted two claims to fame. More than 45 young men from those two streets saw active duty in World War II. Nearly all were first generation Americans whose parents immigrated to Oil City. And, the tiny neighborhood was home to the Ukrainian National Aid Association which was located in the Ukrainian Hall at 13 Standard Street. In all, the two streets just off North Seneca Street had a population of about 50 families. The neighborhood was one of three main neighborhoods where Polish, Ukrainian, Hungarian and Russian families settled. The others were Palace Hill and the Union Street area.

The Ukrainian Hall was a popular place for wedding receptions, neighborhood parties, social gatherings and more, according to newspaper accounts. A city directory notes that Felix Kozek resided in a small apartment in the hall in the 1950s. The neighborhood was earmarked in the mid-1960s for a redevelopment project designed to upgrade housing for residents of the two intersecting streets.

The city launched its Standard-Stevens project in May 1970. The $1.7 million project would result in the demolition of all homes on those two streets.

Written by Judy Etzel with research by Kay Dawson and design by Natalie Cubbon.

HIDDEN HERITAGE IS SPONSORED BY:

Oil Region Alliance

Belles Lettres Club of Oil City

Gates & Burns Realty

Support This Project

Donations to the library are appreciated to help offset printing costs & make this project possible! Want to become a sponsor? Email us at promotions@oilregionlibraries.org to get started!

Make a Donation